Water Security in the Wake of Arizona v. Navajo Nation: How the President’s Emergency Powers Can Provide a Path Forward for the Navajo Nation

In 2023, the Supreme Court decided Arizona v. Navajo Nation, finding that the United States government does not have an affirmative duty to ensure the Navajo Nation’s water security. The decision offers the Navajo two paths forward for relief: the tribe can either litigate specific water rights claims in the Colorado River Basin or lobby the President and Congress to amend an 1868 treaty, the language of which served as the basis for the holding in Navajo Nation. These paths forward are not without problems. Litigating water rights claims is costly and time-intensive, sometimes taking decades to be decided. As for lobbying Congress, only six of the 435 Members of Congress identify as Indigenous Americans. With such little representation in Congress, the ability of Indigenous Americans to affect change via the legislature may prove challenging. This Comment offers a third path forward via the executive branch, specifically through the President’s emergency powers.

This Comment evaluates two of the four statutes that authorize the President’s emergency powers: the National Emergencies Act (“NEA”) and Stafford Act. Ultimately, this Comment identifies the Stafford Act as the best prospect for the Navajo to advance their water rights, given that there is a specific process in place for tribal leaders to request an emergency declaration from the President that would release federal funds. The Stafford Act also has a more flexible understanding of what is meant by “national” and “disaster,” which might allow the Navajo to receive financing for water infrastructure and drought-resilience initiatives in the states it spans. While the Stafford Act has historically provided financial relief for rapid-onset disasters, there has been a greater shift toward applying the Act to slow-onset disasters like droughts. Moreover, the Biden Administration is emphasizing a bottom-up approach by building the capacity of tribes to successfully request federal assistance. The Stafford Act thus provides a promising alternative to the Navajo to enhance their water security following Navajo Nation and in the face of a changing climate.

I. Introduction

Climate change and its accelerating effects often frame the way Americans think about their future and the security of their communities.1 Watersheds across the American Southwest have been bombarded for years by record-breaking heat, and some municipalities now face a future without replenishable groundwater.2 Commentators warn that the effects of extreme weather, climate migration, and climate-driven food and water insecurity will destabilize the ability of states to effectively respond to the current and coming crises.3 Native American tribes like the Navajo Nation, whose reservation spans drought-parched areas of Arizona, New Mexico, and southern Utah, may be particularly vulnerable because they lack the infrastructure and resources to adapt to increasingly extreme weather variations.4 In response to the global climate crisis, some prominent politicians have called on the President to declare a national climate emergency and wield presidential emergency powers against the effects of climate change.5

Water security for the Navajo Nation is particularly dire. Nearly one-third of the Navajo living on the reservation lack access to safe drinking water and, of those, “thousands . . . must drive for miles to refill barrels and jugs to haul water home for drinking, cooking, bathing and cleaning.”6 Greater water insecurity also jeopardizes Navajo agricultural production, which currently nets $92 million in profits annually.7 In fiscal year 2024, the total gross revenue projection for the Navajo Nation was $216.6 million.8 Moreover, drought conditions are forcing many Navajo off tribal lands.9 Mario Atencio, a board member of a Navajo-run environmental nonprofit, remarked:

Even now, people are selling their cows. It’s kind of happening. There are no jobs, you can’t raise and sustain a herd of cows, what else are you going to do? You’ve got to go work. It’s not going to be a mass migration. It’s happening very slowly, a climate change diaspora.10

In June 2023, the Supreme Court assessed the Navajo Nation’s water insecurity in Arizona v. Navajo Nation.11 At the center of this case was an 1868 peace treaty that established the Navajo Reservation.12 The treaty’s terms promised the Navajo a “permanent home.”13 Navajo Nation evaluated the meaning behind and implications of “permanent home;” that is, whether the promise of a “permanent home” requires the United States government to afford the Navajo access to water. Specifically, the majority framed the case as adjudicating whether the treaty “requires the United States to take affirmative steps to secure water for the Navajos.”14 After reviewing and strictly construing the treaty, the Supreme Court found that the treaty contained “no ‘rights-creating or duty-imposing’ language that imposed a duty on the United States to take affirmative steps to secure water for the Tribe.”15 Without such rights-creating or duty-imposing language, the Court held that “nothing in the 1868 treaty establishes a conventional trust relationship with respect to water.”16

Justice Gorsuch’s dissent in Navajo Nation framed the case differently, challenging the majority’s focus on duty and affirmative steps. Justice Gorsuch instead focused on whether the United States must identify the water rights that are federally held for the Navajo; that is, how much water from the Colorado River they can abstract.17 Whether one accepts the majority or dissent’s framing of Navajo Nation, it is clear that the current Supreme Court is unlikely to read tribal treaty language as expanding federal obligations. Navajo Nation appears to close one door to judicial relief for securing tribal water rights. But while the judiciary may fail to provide the Navajo with greater water security, the executive branch may prove a viable alternative given the breadth of the President’s emergency powers. These powers have equipped the President with the authority to “take over domestic communications, seize Americans’ bank accounts, and deploy U.S. troops to any foreign country.”18 Therefore, analyzing the role of presidential emergency powers to relieve the effects of climate change within tribal lands is particularly timely.

This Comment aims to challenge our conception of what is considered to be “national security.” Firstly, water insecurity in the Navajo Nation is a national security issue. It threatens the Navajo’s economic, food, and public health security. In particular, water insecurity has implications on the United States’ broader national security interests, including the spread of diseases. The Navajo are “67 times more likely than other Americans to live without running water.”19 During the COVID-19 pandemic, unreliable water access exacerbated the spread of disease within reservations, contributing to a death rate among Indigenous Americans “twice [that] of white Americans.”20 Infectious diseases that defy borders are one such threat to national security, along with food, livelihood, and economic insecurity posed by poor access to reliable water sources.

Secondly, the size, geographical reach, and sovereign nature of the Navajo Nation raise questions surrounding our understanding of a “nation” and what is considered “national.” Regarding size and geographical reach, the Navajo Nation has approximately 300,000 enrolled members, over half of whom reside on tribal land stretching 17 million acres across three states.21 The Navajo Nation is larger in acreage than ten other states.22 As for sovereignty, the United States Constitution recognizes the unique sovereignty of tribal nations.23 Tribal sovereignty allows tribes “to punish tribal offenders . . . to determine tribal membership, to regulate domestic relations among members, and to prescribe rules of inheritance for members,” so long as they do not exceed what is necessary for self-government and internal relations.24

Given the national security concerns created by water insecurity and climate change, this Comment considers whether a legal solution within the national security legal apparatus—the President’s emergency powers—could provide much-needed relief for the Navajo Nation. Section II provides a background on Indigenous water rights in the United States, beginning with a history of relevant Supreme Court decisions and culminating with Navajo Nation. Section III dives into Navajo Nation and the barriers to relief following this decision. Section IV then describes the water and climate crises in the Navajo Nation, followed by an overview of the President’s emergency powers. Section V evaluates the National Emergencies Act (NEA)25 and the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (“Stafford Act”)26 as two potential solutions to the Navajo Nation’s water crisis, concluding that the Stafford Act is a more effective means for addressing the problem of water insecurity facing tribal nations.

II. History of Indigenous Water Rights

Section II will provide a history of indigenous water rights litigation, beginning with an early and pivotal case, Winters v. United States, which served as the interpretive basis for examining the Navajo Nation’s claim in Arizona v. Navajo Nation. Following Winters, this section will review the key takeaways from Arizona v. California, Arizona v. San Carlos Apache Tribe of Arizona, Nevada v. United States, and United States v. Powers regarding the Court’s treatment of Indigenous water rights claims.

While Navajo Nation is the most recent piece of water rights litigation brought forward by Indigenous Americans, it is not the first. In 1908, the Supreme Court considered the water rights of the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation in Winters v. United States.27 The federal government litigated the case on behalf of the Montana-based tribe to prevent the damming of the Milk River by non-Indigenous settlers.28 The Milk River flowed into the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation and supported the tribe’s pastoralist and agrarian activities, as well as domestic and culinary needs.29 The non-Indigenous settlers attempted to assert their rights under the prior appropriation doctrine, claiming that they had diverted and otherwise used the Milk River before the Fort Belknap Indians had done so; therefore, first in time, first in right.30 However, the Court rejected this claim and ruled in favor of the reservation, relying on its interpretation of the 1888 agreement31 that had established the reservation.32 The Court held that while the agreement did not explicitly detail the Fort Belknap Indians’ water rights, it could be implicitly read into the agreement.33 Specifically, the Court found that the tribe would not have agreed to a treaty that reduced the size of their land to an arid tract without access to the Milk River; otherwise, the land would be valueless and tribal members would be unable to pursue agrarian livelihoods.34

A series of water rights disputes between Arizona and California over the Colorado River Compact followed Winters, beginning in 193135 and ending in 2006.36 Established in 1922, the Colorado River Compact allocated the flow of the Colorado River between seven states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming.37 Notably, the thirty Native American tribes located in the Colorado River Basin, including the Navajo Nation, were excluded from this compact.38 In 1963, however, the Court in Arizona v. California39 addressed the rights of five of those tribes—Chemehuevi, Cocopah, Yuma, Colorado River and Fort Mohave—residing in Arizona, California, and Nevada. There, the Court addressed (1) how much of the tribal lands were irrigable, (2) the amount of the Colorado River the tribes were entitled to, and (3) what the priority dates of those rights were, holding that “enough water was reserved to irrigate all the practicably irrigable acreage on the reservations.”40

Other water rights claims litigated by Indigenous Americans include Arizona v. San Carlos Apache Tribe of Arizona,41 which expanded jurisdiction over indigenous water rights to state courts; Nevada v. United States,42 which affirmed an earlier decree that specified the water rights of the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe to the Truckee River; and United States v. Powers,43 which held that water rights reserved for tribal members continued in the land to subsequent landowners. These cases help clarify the rights of tribes to water resources on tribal lands, and moreover, provide insight into the Court’s interpretation of treaties and settlement agreements between tribes and the United States. These interpretations also shed light on the federal government’s intent surrounding the grant of water rights to tribes. Ultimately, the most recent culmination of these Indigenous water rights cases was Navajo Nation.

III. The Navajo Nation Litigation

This section provides an overview of Navajo Nation, including the reasoning and holding of the majority and dissent. The majority holds that there is no affirmative duty by the United States government to provide water for the Navajo, while Justice Gorsuch in his dissent argues that the Navajo are litigating a different issue entirely; that is, a proper accounting of the water they are entitled to extract from the Colorado River Basin. The section then evaluates issues with the Court’s recommendation that the Navajo proceed by litigating specific water rights claims in the Colorado River or lobbying Congress and the President to amend the language of an 1868 treaty at the core of Navajo Nation. It also raises problems affiliated with the Department of Interior’s negotiated water rights settlements.

A. Overview of Navajo Nation

Navajo Nation, decided by the Supreme Court in 2023, was the result of decades-long breach-of-trust litigation between the Navajo and the federal government, specifically the Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, and Bureau of Reclamation, over an 1868 peace treaty (“Treaty Between the United States of America and the Navajo Tribe of Indians”).44 The treaty created the Navajo Reservation in order to end warfare between the tribe and the United States and granted the Navajo certain land and water rights.45 Relying on this treaty, the Navajo “sought to ‘compel the Federal Defendants to determine the water required to meet the needs’ of the Navajos in Arizona and to ‘devise a plan to meet those needs.’”46 Specifically, the Navajo Nation sought clarification as to the amount of water they had rights to in the Colorado River because they were excluded from the 1922 Colorado River Compact.47 Arizona, Nevada, and Colorado intervened in the case to preserve their riparian rights as settled by the 1922 Compact.48

The Supreme Court held that the 1868 treaty only established the reservation itself; it did not impose “a duty on the United States to take affirmative steps to secure water for the Tribe.”49 This decision overturned the Ninth Circuit’s finding that the United States has an affirmative duty under Winters50 to secure water for the Navajo Nation.51 The Ninth Circuit had applied Winters and found that the United States was implicitly obligated to provide the Navajo Nation with water “to the extent needed to accomplish the purpose of establishing the Reservation as a permanent homeland for the Navajo people.”52 The Supreme Court disagreed.

Contrary to the approach taken by the Ninth Circuit, the Supreme Court narrowly construed the 1868 treaty and the meaning of “permanent home.”53 The majority’s interpretation of “permanent home” was the lynchpin for the Court’s holding that the treaty’s express terms only established the reservation itself.54 The treaty did not contain any explicit language imposing “a duty on the United States to take affirmative steps to secure water for the Tribe . . . As this Court has stated, ‘Indian treaties cannot be rewritten or expanded beyond their clear terms.’”55

In his dissent, Justice Gorsuch, writing with Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson, claimed that the majority mischaracterized the Navajo Nation’s claim. The Navajo Nation did not seek judgment on whether the federal government had an affirmative duty to secure water for them; rather, they want the United States to carry out an assessment calculating how much water flowing through their reservation they are entitled to and “if the United States has misappropriated the Navajo’s water rights, the Tribe asks it to formulate a plan to stop doing so prospectively.”56 As Justice Gorsuch writes, “Everyone agrees the Navajo received enforceable water rights by treaty. Everyone agrees the United States holds some of those water rights in trust on the Tribe’s behalf. And everyone agrees the extent of those rights has never been assessed.”57

The dissent’s argument is rooted in a historical understanding of the context preceding, during, and following the Navajo Nation and United States’ negotiation of this treaty.58 Prior to drafting the treaty in 1868, the United States government removed the Navajo from their traditional lands (before eventually moving them back as a result of this treaty) as a way to resolve hostilities with the Navajo, as well as gain access to resources onsite.59 To accomplish this, the United States forced the Navajo to endure “the Long Walk,” where countless died as they walked hundreds of miles to Bosque Redondo, “a ‘semiarid, alkaline, fuel-stingy, insect-infested environment.’ . . . [where] water proved a serious issue. The Tribe was forced to rely on a ‘little stream winding through an immense plain.’ But its ‘water was bad.’”60 Within four years of relocating to Bosque Redondo and its inhospitable conditions, 2,000 Navajo had died; so, the United States government sought to relocate the Navajo once more.61 The Navajo, however, were adamant that they would only agree to move back to their traditional lands where they knew “the water flows in abundance.”62 Considerations involving water quality and quantity became a core theme in the negotiations surrounding the 1868 treaty.63

While the dissent argued that water generally was implicitly promised when negotiating a permanent home for the Navajo, the amount was never determined. Throughout the ensuing decades, the Navajo had continuously and explicitly sought for the United States to assess their water rights. They did not necessarily demand the United States to finance and install infrastructure and other means to access this water. This history, which includes failed motions in 1956 (“seeking ‘to define the scope of the representation of the [T]ribes by the United States’”)64 and 1961 (“argu[ing] that the United States had failed to vigorously assert’ their interests [by denying the 1956 motion]”)65 , reinforces that the Navajo Nation sought an assessment of their water rights, contravening the majority’s understanding of what the Navajo Nation’s claim was here.

In light of this abovementioned context, the dissent then applies contract law to defend its interpretation of the treaty, taking into consideration the parties’ intent, principles of good faith and fair dealing, and the doctrines of contra proferentem66 and unilateral mistake67 , as well as the Indian canon68 . When applying these principles and canons of contract law to the facts here, Justice Gorsuch argues that the Navajo Nation would have clearly understood having access to good quality water in sufficient quantities as necessary to achieve the treaty’s purpose of establishing a permanent home for the Navajo.69 Moreover, to further the objectives of the treaty and to comply with its fiduciary duties as a trustee of the Navajo’s water rights, the United States must carry out an assessment of those water rights on behalf of the Navajo.70 However, the majority does not agree that this is the point at issue in this case. As Justice Gorsuch describes it, “[r]eally, the Court gets off the train just one stop short.”71

The majority’s understanding—or, arguably, misunderstanding—of the Navajo Nation’s claim and its subsequent holding maintained the status quo for the tribe in a time when water insecurity is anticipated to rise in the face of a changing climate. Specifically, by the treaty’s terms in accordance with the majority’s analysis, there is no obligation on the part of the United States government to enhance the Navajo Nation’s water security. The dissent likened this decision’s impact on the Navajo Nation to going to the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV):

The Navajo have waited patiently for someone, anyone, to help them, only to be told (repeatedly) that they have been standing in the wrong line and must try another. To this day, the United States has never denied that the Navajo may have water rights in the mainstream of the Colorado River (and perhaps elsewhere) that it holds in trust for the Tribe. Instead, the government’s constant refrain is that the Navajo can have all they ask for; they just need to go somewhere else and do something else first.72

Following their loss in Navajo Nation, the Navajo have been told to stand in one of two other “lines” at the majority’s DMV: litigate other water rights claims73 or change the terms of the 1868 treaty through the political process.74

B. Barriers to Relief Post-Navajo Nation

As noted above, the Court in Navajo Nation offered two alternate paths forward for relief for the Navajo Nation: the tribe could either intervene in other water rights litigation, including that pertaining to the Colorado River,75 or lobby Congress and the President to update the 1868 treaty to expressly include such an affirmative duty.76 These options pose their own challenges. Litigating water rights claims in court can take several years, if not decades.77 The Navajo Nation case, for instance, was initiated twenty years earlier in 2003.78 Additionally, Indigenous Americans are among the most politically disenfranchised groups in the United States as a result of socioeconomic barriers and a long history of voter suppression, so they may lack the ability to effectively lobby Congress to amend the 1868 treaty.79 Currently, of the 435 members of Congress, only six are Indigenous Americans.80

Beyond litigation, negotiated settlements serve as another means to address Indigenous water rights.81 While negotiated settlements have officially been part of the Department of Interior’s policy since 1990, there have been thirty-five congressionally-enacted and four administratively-approved Indigenous water rights settlements dating back to 1984, two of which—from 2009 and 2020—involve the Navajo Nation.82 In May 2024, the Navajo Nation, along with the Hopi and San Juan Southern Paiute tribes, approved of a proposed settlement amounting to $5 billion that will deliver water via a pipeline from the Colorado River by 2040.83 These settlements have already cost the federal government $8.5 billion, “allow[ing] tribes to quantify their water rights on paper, while also procuring access to water through infrastructure and other related expenses.”84 While the settlements serve as an alternative to litigation, they have their own set of issues.

One such challenge relates to identifying, structuring, and enacting federal funding. The renegotiating of settlements can sometimes reduce their costs by hundreds of millions of dollars.85 In addition to financial issues, these settlements may pose challenges to environmental compliance86 or face opposition by the executive branch.87 Tribes negotiating these settlements also experience water supply issues, such as those relating to quantity and quality, due to the reliance on water markets in these agreements and challenges involving identifying and quantifying water sources.88 Finally, tribes have claimed that settlements may actually limit future economic development, including in the agricultural sector, as settlements involve a “specific, permanent quantification of their water rights.”89

A 2023 North Carolina State University study evaluated forty years of data and reinforced these concerns about the efficacy of water rights settlements. The study found that “many tribes are utilizing only a fraction of their entitlements, forgoing as much as $938 million–$1.8 billion in revenue . . . this gap is driven, in part, by land tenure constraints and a lack of irrigation infrastructure.”90 The study concluded that many of these settlements fail to materialize into “wet” (or actual) water for tribes—a problem that will only worsen with climate change, as physical water scarcity threatens to widen the gap between tribes’ legal water rights and the amount actually available for abstraction and use.91

IV. Navajo Water Insecurity and the President’s Emergency Powers

This section first positions the Navajo Nation’s water emergency as a national security issue due to its public health, economic development, and food security ramifications within and outside the borders of the reservation. The section then provides an overview of the President’s emergency powers, specifically the National Emergencies Act (NEA) and Stafford Act. The section defines how these statues, where applicable, define “emergencies” and “major disasters.”

A. The Navajo Nation’s Water Emergency as a National Security Issue

In 2020, then-Navajo Nation President, Jonathan Nez, testified before the United States House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce about the “urgent needs” of tribes, including the need to improve tribal water security.92 Regarding water on Navajo land, Nez stated:

In the arid Southwest, every drop of water is valuable, increasing the need to protect precious water sources and water quality. On the Navajo Nation, over 40 percent of Navajo Nation households do not have running water and rely on hauling water to meet their daily needs. The Navajo Nation currently accesses approximately 20 groundwater aquifers ranging in various depth and capacities. Of the nearly 174,000 Navajo residents across the Navajo Nation, about 30 percent do not have access to reliable, clean drinking water and roughly 40 percent lack running water in their homes. Some people haul water more than 50 miles to replenish their cisterns. Drought is frequent and pervasive on the Navajo Nation and we are in need of reliable and detailed water infrastructure.93

Nez testified that these conditions—inadequate access to piped and potable water—facilitated the outbreak of COVID-19 among the Navajo, impairing their ability to be self-sufficient for ranching, agricultural, and other purposes.94

Conditions in the Colorado River Basin—which is in its twenty-third year of drought95 —not only impact the human, economic, food, and health security of the Navajo but, as a result, also jeopardize the security of the United States as a whole. For example, during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Navajo Nation had the highest per capita infection rate in the country.96 Inadequate access to water on the reservation was seen as a leading contributor to the spread of disease among tribal members.97 Critically, infectious diseases like COVID-19 do not pose a threat just to a specific community, as “disease can travel anywhere in as little as 36 hours.”98 Recognizing the destabilizing impacts of pandemics, which can impair national security, the National Intelligence Council issued a related report in April 2022 emphasizing that “[t]he COVID-19 pandemic marks the most significant singular global disruption since World War II, with resultant economic, human security, political, and security implications that are likely to ripple for years to come.”99

Beyond the spread of disease, water insecurity at home and abroad has been widely recognized to jeopardize other U.S. national security interests, including those relating to food, climate, and economic security. In June 2022, for example, Vice President Kamala Harris announced the first-ever White House Action Plan on Global Water Security.100 While internationally focused, the Plan:

[E]levates water security as an essential element of the United States’ international efforts to achieve national security objectives that include increasing equity and economic growth; decreasing the risk of vulnerability to shocks, conflict and instability; building inclusive and resilient societies; bolstering health and food security; advancing gender equity and equality; and tackling climate change.101

The Plan demonstrates how the White House has prioritized global water insecurity as an area of United States national security that must be addressed comprehensively.

In another White House-led initiative, Executive Order 14008 on “Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad,” climate change is further framed as a threat to national security.102 This is demonstrated in “Part I. Putting the Climate Crisis at the Center of United States Foreign Policy and National Security,” which characterizes climate change as “an essential element of United States foreign policy and national security” and sets out to develop a climate finance plan to be submitted to the Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs.103 Agencies are also required to submit to the Assistant to the President “strategies and implementation plans for integrating climate considerations into their international work.”104 These include the preparation of a National Intelligence Estimate by the Director of National Intelligence on the climate crisis’ national security implications; the preparation of a Climate Risk Analysis by the Secretary of Defense; and the incorporation of climate change into the National Defense Strategy, Defense Planning Guidance, and other relevant documents and processes by the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Secretary of Homeland Security.105 Recognizing the critical link between climate change and water resource management, the Executive Order references “water” twenty-five times.106

Given the national security dimensions to the Navajo Nation’s water crisis, along with the aforementioned challenges to water rights litigation and settlements, this Comment considers another avenue to enhance water security for the Navajo Nation: the President’s emergency powers.

B. The Application of the Presidential Emergency Powers

Although the Constitution makes no reference to the word “emergency,” it vests Congress and the President with significant implied powers during emergencies.107 Following the Second World War, Congress formalized the constitutional principles of the emergency powers into the statutory structure used today.108 The statutory scheme has expanded into a web of 137 distinct provisions and four governing statutes controlling emergency power response.109 The four governing statutes include the Public Health Service Act, National Emergencies Act (NEA), Stafford Act, and another statute relating to international military assistance.110 Each statute covers different subject matter areas, triggering language for emergency declarations, delegations of authority, and activities that fall within the scope of the emergency power.111 The NEA and the Stafford Act have domestic applications most relevant to climate change and its impacts, including drought.112 The following section examines both statutes and argues that the Stafford Act is best positioned to provide relief for the Navajo following Navajo Nation.

The relevant text of the NEA states: “With respect to acts of Congress authorizing the exercise, during the period of a national emergency, of any special or extraordinary power, the President is authorized to declare such national emergency.”113 In contrast, the Stafford Act enables the state governor or the tribal chief executive to request federal assistance in the event of a disaster or emergency.114 The Stafford Act frames “disasters” as natural catastrophes that have already occurred.115 However, the Stafford Act defines “emergency” more broadly as any instance when the President determines that “[f]ederal assistance is needed to supplement State and local efforts and capabilities to save lives and to protect property and public health and safety, or to lessen or avert the threat of a catastrophe.”116

The NEA and the Stafford Act differ in what constitutes an “emergency” and the powers they authorize. In what follows, this Comment examines their respective applications in a regional context—given the geographical breadth of the Navajo Nation—and to slow-onset emergencies like drought.

C. Background on the NEA

Since its passing in 1976, the NEA has been the most invoked statutory framework for emergency powers.117 The NEA authorizes the President to discretionally declare a national emergency, but it lacks a statutory definition for “national emergency.” In effect, “this allows the President to invoke this authority capaciously to address a remarkably diverse set of emergencies.”118 Emergencies have been declared through the NEA scheme on issues from the 9/11 terrorist attacks and numerous international humanitarian crises like the South African apartheid and the Russia-Ukraine war, to less traditional security threats, such as the 2009 H1N1 pandemic and securing the southern border with a large wall.119 For example, in Sierra Club v. Trump,120 the plaintiffs successfully halted the funding of a southern border, which was authorized through a statute enabled by President Donald Trump’s declaration of a NEA emergency at the border.121 Neither party contested whether the issue at the southern border legally qualified as a national emergency under the NEA, nor whether President Trump could declare the situation an emergency.122 The discretion to declare any issue a national emergency, therefore, is effectively delegated to the President.123

In the absence of a statutory definition, commentators have found two factors common to emergencies declared under the NEA: emergencies are (1) exceptional and (2) severe.124 Although no cases directly confront the issue of climate change, the clear threat posed by climate change to United States national security can be appropriately characterized as exceptional and severe.

One concern with this application—that is, emergencies are exceptional and severe—is that as climate catastrophes occur with more regularity, they inherently become less exceptional. This, however, likely does not bar the NEA’s application to the climate crisis. In employment law, for example, a violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964125 requires that workplace conduct be severe or pervasive.126 The Court considers the totality of the circumstances to determine whether a workplace is hostile, including “frequency of the discriminatory conduct; its severity; whether it is physically threatening or humiliating, or a mere offensive utterance; and whether it unreasonably interferes with an employee’s work performance.”127 This encompassing approach taken in employment law could serve as a model for courts interpreting climate emergencies in the context of the NEA. Regarding climate catastrophes, even if disasters become less exceptional as they occur with increasing frequency, their regularity also makes the human and economic toll of these disasters more severe. So, drawing parallels from employment law—including a consideration of the totality of the circumstances—a court would likely still find it valid to apply the NEA to the climate crisis, especially as “emergency” is undefined by the NEA.

D. Background on the Stafford Act

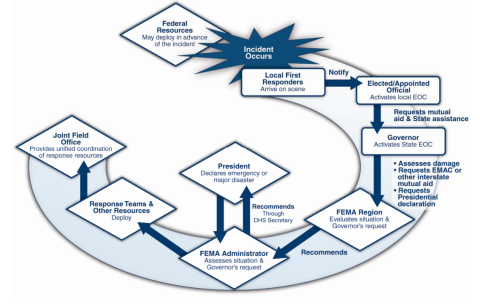

Under the Stafford Act, once a tribal executive or governor requests assistance, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) issues a recommendation for the President to act on the request.128 The presidential declaration of emergency includes the geographic bounds of the emergency (in the Navajo’s case, this would be the entire reservation, as tribal lands cannot be subdivided for FEMA’s relief purposes), the specific federal assistance programs that are being activated (i.e., individual assistance, public assistance, or hazard mitigation assistance), and the federal financial burden of the emergency.129

Unfortunately, many of these programs do not neatly fit the demands of slow-onset climate events like droughts. Slow-onset disasters are defined by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change as those that “evolve gradually from incremental changes occurring over many years or from an increased frequency or intensity of recurring events.”130 The above-mentioned federal assistance programs include FEMA’s Public Assistance Program, Community Disaster Loan Program, Fire Management Assistance Grant Program, Individual and Households Program, Other Individual Assistance Programs, and Hazard Mitigation Assistance.131 Most of these programs provide immediate assistance following acute disasters like floods and hurricanes and are typically responsive, rather than mitigative, in nature.132 Effects of climate change that take years to develop and inflict damage, like the long-lasting and pervasive effects of drought and water shortages, may not fit the compensation scheme for FEMA programs that reimburse communities for discrete and sudden disasters where the damages may be easier to quantify.133

However, FEMA also provides Hazard Mitigation Assistance that allows for ex-ante efforts to address climate change.134 These “pre-disaster mitigation grants”135 are not as extensive financially as those for emergency response, but they do help tribal governments implement programs to reduce the risk future disasters pose to local populations and infrastructure.136 While these mitigation provisions cannot facilitate massive expansions to the Navajo water network, they do provide a path for some relief, pending a presidential “emergency” or a “major disaster” declaration.

V. The Stafford Act Provides The Better Path Forward for Enhanced Water Security in the Navajo Nation

This section begins by providing a historical understanding of the NEA and its limitations for enhancing the Navajos’ water security, including its narrow understanding of “national.” The section then considers why the Stafford Act provides a better alternative than the NEA to achieve greater water security for the Navajo, weighing both the “emergency” and “major disaster” declarations, as well as introducing the role of tribal leaders in the declaration process. It then concludes by considering the Stafford Act’s federalist structure, which actually benefits tribes given federalism’s emphasis on a bottom-up approach to these emergencies and disasters.

Following Navajo Nation, the Court presented two paths forward for the Navajo to enhance their community’s water security: litigating specific water rights claims in the courts and lobbying Congress and the President to amend the language of the 1868 peace treaty.137 As stated in Section III, these two paths pose challenges to the Navajo, who are in dire need of water security now and whose needs will continue to intensify as climate conditions worsen. Challenges range from the financial and time costs associated with litigation to the lack of political representation, will, and accountability in Congress. The President’s emergency powers, however, can provide a more direct and faster path toward immediate relief for the Navajo as they experience water scarcity. For the President to declare an emergency under the NEA, he needs only to sign an executive order.138 The Stafford Act, requires slightly more process to declare an emergency than the NEA.139 This shortcoming of the Stafford Act is offset by its streamlined procedures to ensure immediate assistance. For example, within twenty-four hours of a Stafford Act declaration of COVID-19 as an emergency on March 13, 2020, FEMA had obligated $100 million for emergency assistance.140

Figure 1: FEMA Overview of Stafford Act Support to States141

A. The Historical Understanding and Structure of the NEA Hinders its Application to the Navajo Nation’s Water Crisis

In July 2022, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) carried out an analysis on the NEA and Stafford Act and whether they could be used to declare a national climate emergency.142 While CRS found that neither precluded the President from declaring a national climate emergency, it noted that each act posed its own challenges.143 The NEA has historically been understood to protect the nation as a whole, not a particular community.144 Based on this historical understanding, it would be difficult to justify the application of the NEA to the water crisis confronting the Navajo Nation. While the reservation spans three states, this likely does not fit within an ordinary conceptualization of “national.” A broader understanding of “national” is reinforced by NEA declarations made between 1978 and 2018, examples of which include: enforcing export control regulations and prohibiting certain transactions with adversarial countries; declaring public health emergencies for nationwide epidemic outbreaks; and imposing sanctions against countries that interfered with federal elections.145 Moreover, the NEA alone offers no emergency powers; rather, it provides a structure under which Congress may pass statutes that authorize specific presidential emergency powers.146

There are 148 statutory provisions available for the President’s use once he declares an emergency under the NEA.147 Most of these authorizing provisions are restricted for use only in particular types of emergencies (such as only in times of war or in pandemics), but some have broader applications that may be relevant to addressing climate change.148 One such broad statute that can be triggered by an NEA declaration, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA),149 empowers the President to regulate financial and other commercial transactions “to deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States.”150 Commentators have argued that the President may be able to use IEEPA-delegated powers to confront climate change by sanctioning “climate rogue states” and regulating high-emission trade.151 Domestically, the President may address a climate emergency by turning to authorizing provisions that delegate regulatory control of transportation, military construction, and loan guarantees to relevant industries.152 These theoretical applications of the NEA and its authorizing provisions to solve the climate crisis are confined to climate mitigation rather than adaptation (e.g., drought resilience) measures, as well as to national, rather than regional or local, emergencies.

When looking at drought conditions in the Navajo Nation, finding an appropriate statutory provision to serve as the needed hook for this type of localized emergency may be an additional barrier under the NEA. Additionally, the statutory provision would need to be one that authorizes the President to fund climate adaptation projects that strengthen the Navajo’s resilience against drought and ensure greater water security for its tribal members. Although courts do not review the initial declaration of an emergency under the NEA, courts “still serve as a partial check when the internal requirements of an authorizing statute are violated.”153 Therefore, even if the President has the discretion to declare a climate emergency in the Navajo Nation, the decision to use authorizing provisions with restricted applicability to particular emergencies may be challenged. Thus, the Stafford Act may provide greater flexibility to the President and the Navajo Nation, especially as declaring an “emergency” does not preclude the President from also declaring a “major disaster” and vice-versa.154

B. The Stafford Act Provides Greater Flexibility to the Navajo Nation as They Seek to Enhance Their Water Security

Unlike the NEA, the Stafford Act allows for a tribal executive to recommend that the President declare an “emergency” or “major disaster” on tribal lands.155 This is a powerful tool at the disposal of the Navajo Nation and its leadership. The Stafford Act defines a “major disaster” as a “natural catastrophe . . . in any part of the United States, which in the determination of the President causes damage of sufficient severity and magnitude to warrant major disaster assistance under this chapter to supplement the efforts and available resources of States, local governments, and disaster relief organizations.”156 In contrast, an “emergency” is defined as any instance when the President determines that “[f]ederal assistance is needed to supplement State and local efforts and capabilities to save lives and to protect property and public health and safety, or to lessen or avert the threat of a catastrophe.”157 While the President makes the final determination as to what is or is not a major disaster or emergency, tribal leaders can still request such a declaration be made.

Historically, the Stafford Act has been invoked for “rapid-onset events [e.g., flash floods, hurricanes, earthquakes] that cause a measurable amount of damage in a particular geographic area over a defined period of time” unlike slow-onset climate change disasters, such as drought.158 However, while climate change has historically been thought of as a slow burn, the rate of climate change is increasing by as much as fifty percent within the next several decades.159 Likewise, globally, the frequency and length of droughts has increased by twenty-nine percent since 2000.160 A team at the University of Colorado Boulder recently published a study on “fast-onset droughts” or “flash droughts,” finding that their onset rates in the United States were the fastest between 2011 and 2021 when looking at the last seventy years.161 These flash droughts can arise in weeks and last for months or years.162

Given the quickly changing nature of climate and drought disasters—from what was once thought of as slow- to rapid-onset disasters—this historic and limited application of the Stafford Act to rapid-onset disasters like hurricanes and floods may prove obsolete. Moreover, given that “major disaster” and “emergency” are broadly defined statutory terms, there is likely a great degree of flexibility and discretion regarding the inclusion of droughts. The Stafford Act’s definition of “emergency,” for example, could address pervasive water insecurity in the American Southwest and accompanying ex-ante considerations. An “emergency” can be declared by the President by recommendation of a governor or tribal executive for any instance requiring federal assistance to save lives.163 By its terms, a discrete disaster, such as a flood or hurricane event, is not necessary for the President to declare an “emergency.”164 However, the shortcomings of an “emergency” versus a “major disaster” declaration rest on the type of assistance rendered and the scope of the activities covered therein.

C. Declaring a “Major Disaster” Avails Federal Funding for Water Projects on Indigenous Lands

Once the President declares a “major disaster,” federal funding becomes available for FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP).165 Funding is also available after the President issues an “emergency” declaration. However, “the assistance [limited to Individual Assistance and Public Assistance] provided for a single emergency declaration is capped at $5 million, though it may (and often does) exceed the cap upon the President’s determination that continued emergency assistance is required.”166 Individual Assistance is a funding scheme made available for individual beneficiaries to, for example, repair their home following a disaster.167 The Public Assistance scheme is awarded to state and local government entities and nonprofit organizations “for urgent emergency response activities (emergency work) as well as long-term reconstruction (permanent work) . . . Mitigation projects account for a fraction of these historical obligations.”168

HMGP funding cannot be awarded without a specific request from a tribal (or state or local) government.169 This funding is not restricted to a particular disaster and, in fact, FEMA produced a “Drought Mitigation: Hazard Mitigation Policy Aid” guide in September 2023 to assist state, local, and tribal governments seeking to request HMGP funding for droughts.170 Qualifying projects include but are not limited to those projects that build drought resilience through nature-based solutions, early warning systems, aquifer recharge, storage and recovery, floodplain and stream restoration activities, flood diversion and storage, and stabilization projects.171 Moreover, applicants are encouraged to propose their own projects beyond those already listed.172

While HMGP funding is a seemingly attractive path forward for the Navajo Nation to secure funding for the construction of water infrastructure and implementation of climate adaptation initiatives toward greater water security, there are several challenges. First, there are statutory spending caps for mitigation projects, which are also largely underfunded by Congress.173 HMGP funding, for instance, is awarded based on a sliding scale, which is restricted to the “percentage of the estimated total federal assistance under the Stafford Act for the declaration.”174 Second, “FEMA’s role in funding projects that minimize or prevent slow-onset, compounding, or cascading disasters like desertification, sea-level rise, and coastal erosion” has yet to be defined.175 This ambiguity impacts the way in which FEMA assesses losses from such disasters, including “whether to recommend the President authorize PA [Public Assistance] and/or IA [Individual Assistance] for a major disaster,” which is generally confined to an “incident period” or “single event.”176 Third, FEMA funding has historically been directed to white and higher socioeconomic status communities.177

Finally, tribal communities may face unique additional barriers to receiving FEMA funding. These include a lack of resources and expertise needed to produce Hazard Mitigation Plans or other plans that are condition precedent to receiving federal funds.178 Moreover, FEMA funding generally requires that the tribal (or state or local) government contribute ten to twenty-five percent of the total cost of the project, which can prove difficult for many cash-strapped tribal communities.179 That being said, while there may be political, procedural, and financial challenges associated with the Stafford Act and HMGP funding, there does not appear to be any legal impediment to the Navajo Nation recommending that the President declare a “major disaster” to address its water crisis.

D. Using the Stafford Act to Address the Navajo Nation’s Climate Crisis Does Not Necessarily Strain its Federalist Framework

The Congressional Research Service raises the concern that using the Stafford Act to declare a climate emergency would “strain [its] federalist framework . . . as well as [cause] significant changes to FEMA’s operations.”180 This federalist framework is built on a “bottom-up” approach to emergency management, which is led by local, tribal, state, and territorial governments, and supplemented by the federal government’s assistance.181 At the heart of this federalism concern is that “Stafford Act declarations generally authorize limited federal support for rapid-onset events that cause measurable damage in a particular geographic area during a defined period of time. Establishing temporal and spatial limits for a climate change emergency could prove impossible.”182 This is further complicated by the fact that the resources of many sub-federal governments are already constrained.183

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, for example, the Stafford Act’s federalist structure was seen as a contributing factor to the federal government’s poor response because the government’s ability to provide assistance hinged on the actions of local and state governments.184 This federalist system establishes a more reactive, as opposed to proactive, response to emergencies and major disasters.185 A reactive system is not ideal in the case of climate change-induced droughts, where climate adaptation measures—like those funded by the HMGP—can effectively mitigate and prevent some of the worst water-related outcomes, such as inadequate access to safe drinking water, crop failure, livelihood insecurity, and migration.186 While many commentators support greater centralization of emergency management, some note that the shortfall in the federal government’s response to Hurricane Katrina was not necessarily federalism, but rather “the federal government’s failure adequately to exercise its existing powers.”187

While the practical impacts of the Stafford Act’s federalist structure have been subject to these critiques, it is the bottom-up approach of providing relief that makes it an alluring option to the Navajo Nation. Otherwise, the Navajo Nation would be subject to the whims of the President alone, Congress, and the courts as they seek access to clean and reliable water in the face of a changing climate. Given the bottom-up approach of the Stafford Act and, specifically, the addition of the Sandy Recovery Improvement Act188 —a 2013 amendment to the Stafford Act which allows tribal governments to directly request the President to issue a declaration—the Navajo Nation may take on these matters through more direct means.189 Toward these ends, FEMA released its first-ever national tribal strategy in August 2022, and it established a FEMA Tribal Affairs Work Group to support tribes as they navigate FEMA funding and administrative processes, resulting in greater and more effective collaboration with the federal government.190

VI. Conclusion

In the wake of Navajo Nation, the President’s emergency powers should be seen as a viable tool for the Navajo as they work toward greater water security in the drought-prone Southwest. While the Navajo retain the ability to litigate water rights claims in the Colorado River and lobby Congress and the President to amend the 1868 peace treaty, they should also consider the Stafford Act as part of their legal and political arsenal. The Stafford Act—which Commentators have recently begun to explore for its potential utility in addressing the climate crisis—would provide the Navajo Nation with the ability to directly influence the President from the bottom-up by recommending that he issue an “emergency” or “major disaster” declaration.

Furthermore, FEMA funding schemes such as HMGP and other programs are beginning to embrace drought resilience measures. FEMA is also finding ways to further empower tribal executives to effectively collaborate with the federal government in solving their water scarcity problems. While historically the application of the Stafford Act has been limited to rapid-onset disasters and a more reactive response by federal and sub-federal governments, the trend appears to be moving toward addressing more (what was once thought of as) slow-onset disasters. There is also a greater appreciation for proactive, preventative, and mitigative efforts as is evinced by the HMGP and other FEMA programs. The language of the statute, which does not preclude climate change, allows for such flexibility to address new and emerging issues like drought, including flash droughts, and should be deployed by the Navajo to meet their immediate and long-term water needs. With Arizona v. Navajo Nation hindering, if not foreclosing, certain paths forward for relief for the Navajo, the President’s emergency Stafford Act powers are one more tool in the toolbox toward greater water security.

- 1See Alec Tyson & Brian Kennedy, How Americans View Future Harms from Climate Change in Their Community and Around the U.S., Pew Rsch. Ctr. (Oct. 25, 2023), https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2023/10/25/how-americans-view-future-harms-from-climate-change-in-their-community-and-around-the-u-s/ [https://perma.cc/MHJ3-NK7L].

- 2See Joshua Partlow et al., Arizona’s Water Troubles Show How Climate Change is Reshaping the West, Wash. Post (June 4, 2023, 6:00 AM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2023/06/04/water-shortage-arizona-california-utah-climate-change/ [https://perma.cc/ 9VF4-A3B3].

- 3See Mark P. Nevitt, Is Climate Change a Threat to International Peace and Security?, 42 Mich. J. Int’l L. 527 (2021).

- 4See Annette McGivney, ‘The US Dammed Us Up:” How Drought Is Threatening Navajo Ties to Ancestral Lands, Guardian (Oct. 9, 2022, 6:00 AM), https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/oct/09/the-us-dammed-us-up-how-drought-is-threatening-navajo-ties-to-ancestral-lands [https://perma.cc/79CT-DT3H].

- 5See Rachel Frazin, Senate Liberals Press Biden For Climate Emergency Declaration, Hill (Oct. 4, 2022, 3:40 PM), https://thehill.com/policy/energy-environment/3673891-senate-liberals-press-biden-for-climate-emergency-declaration/ [https://perma.cc/RLQ5-2X55].

- 6Becky Sullivan, The Supreme Court Wrestles With Questions Over the Navajo Nation’s Water Rights, NPR (Mar. 20, 2023, 7:02 PM), https://www.npr.org/2023/03/20/1164852475/supreme-court-navajo-nation-water-rights [https://perma.cc/WV5Z-UFGU].

- 7Drought in the Navajo Nation, Climate Engine, https://climateengine.com/story/drought-in-the-navajo-nation/ [https://perma.cc/KK47-A99Z] (last visited Aug. 13, 2023).

- 8The Navajo Nation Office of Management and Budget, BFJY-15-23, The Navajo Nation Fiscal Year 2024 Budget Instructions Manual 8 (2023).

- 9See Susan Dunlap, For Families of Color, Climate Change in New Mexico is Already Here, Say Experts, NM Pol. Rep. (Jul. 26, 2021), https://nmpoliticalreport.com/news/for-families-of-color-climate-change-in-new-mexico-is-already-here-say-experts/ [https://perma.cc/6MA5-KFTK].

- 10Id.

- 11See 599 U.S. 555, 570 (2023).

- 12Treaty Between the United States of America and the Navajo Tribe of Indians, Navajo-U.S., June 1, 1868, 15 Stat. 667.

- 13Id. art. XIII.

- 14Navajo Nation, 599 U.S. at 558.

- 15Id. at 564 (citing United States v. Navajo Nation, 537 U.S. 488, 506 (2003)).

- 16See id. at 566.

- 17See id. at 574 (Gorsuch, J., dissenting).

- 18Emergency Powers: Overview, Brennan Ctr. for Just., https://www.brennancenter.org/issues/bolster-checks-balances/executive-power/emergency-powers [https://perma.cc/KAL9-FWLJ].

- 19Nina Lakhani, Tribes Without Clean Water Demand an End to Decades of US Government Neglect, Guardian (Apr. 28, 2021, 5:00 AM), https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/apr/28/indigenous-americans-drinking-water-navajo-nation [https://perma.cc/9PWY-L49J].

- 20Id.

- 21Navajo Nation, 599 U.S. at 559.

- 22History, Navajo Nation Gov’t, https://www.navajo-nsn.gov/History [https://perma.cc/LH8J-HRBC].

- 23See U.S. Const. art. 1, § 8, cl. 3 (“To regulate Commerce with foreign nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes.”).

- 24Montana v. United States, 450 U.S. 544, 564 (1981).

- 2550 U.S.C. §§ 1601–1651 (1976).

- 2642 U.S.C. §§ 5121–5207 (1988).

- 27207 U.S. 564, 574 (1908).

- 28See id. at 565 (statement of McKenna, J.).

- 29See id at 566.

- 30See id. at 568–69.

- 3125 Stat. 113, c. 213 (1888) (“An act to ratify and confirm an agreement with the Gros Ventre, Piegan, Blood, Blackfeet, and River Crow Indians in Montana, and for other purposes.”).

- 32See 207 U.S. at 575–76.

- 33See id.

- 34See id.

- 35See Arizona v. California, 283 U.S. 423 (1931).

- 36See Arizona v. California, 547 U.S. 150 (2006).

- 37Colorado River Compact, 1923 Colo. Sess. Laws 684; Colo. Rev. Stat. §§ 37-61-101 to 104 (1999).

- 38Michael Elizabeth Sakas & Sarah Bures, Indigenous Tribes Were Pushed Away from the Colorado River. A New Generation is Fighting to Save It., CPR News (May 10, 2023, 4:00 AM), https://www.cpr.org/2023/05/10/indigenous-tribes-were-pushed-away-from-the-colorado-river-a-new-generation-is-fighting-for-equity/ [https://perma.cc/6DN6-SFCK].

- 39See Arizona v. California, 373 U.S. 546, 600 (1963).

- 40Id. at 600; see also Arizona v. California, U.S. Dep’t of Just. (Jun. 6, 2023), https://www.justice.gov/enrd/indian-resources-section/arizona-v-california [https://perma.cc/TF7Y-G43G].

- 41See 463 U.S. 545, 559–60 (1983).

- 42See 463 U.S. 110, 144 (1983).

- 43See 305 U.S. 527, 533 (1939).

- 44See 599 U.S. 555, 562; see also Treaty Between the United States of America and the Navajo Tribe of Indians, supra note 12.

- 45See Navajo Nation, 599 U.S. at 558.

- 46Id. at 562.

- 47See id. at 581 (Gorsuch, J., dissenting).

- 48See id. at 562.

- 49Id. at 566.

- 50See 207 U.S. at 567.

- 51See Navajo Nation v. U.S. Dep’t of the Interior, 26 F. 4th 794, 810 (9th Cir. 2022).

- 52Navajo Nation, 599 U.S. at 561.

- 53See id. at 560.

- 54See id.

- 55Id. at 564–65.

- 56Id. at 574 (Gorsuch, J., dissenting).

- 57Id. (emphasis added).

- 58Id. at 575.

- 59Id. at 576.

- 60Id. at 577–78.

- 61Id. at 578.

- 62Id.

- 63Id. at 591.

- 64Id. at 582.

- 65Id.

- 66Id. at 586 (“[A]ny uncertainty in a contract should be construed against the drafting party.”).

- 67Id. (“[T]he notion that, if two parties understand a key provision differently, the controlling meaning is the one held by the party that could not have anticipated the different meaning attached by the other.”).

- 68Id. at 587 (‘The language used in treaties with the Indians should never be construed to their prejudice.’ Rather, when a treaty’s words ‘are susceptible of a more extended meaning than their plain import,’ we must assign them that meaning.”).

- 69Id. at 587–88.

- 70Id. at 589–93 (“Sometimes the United States may hold a Tribe’s water rights in trust. When it does, this Court has recognized, the United States must manage those water rights ‘[a]s a fiduciary,’ one held to ‘the most exacting fiduciary standards,’ This is no special rule. ‘[F]iduciary duties characteristically attach to decisions’ that involve ‘managing [the] assets and distributing [the] property’ of others. It follows, then, that a Tribe may bring an action in equity against the United States for ‘fail[ing] to provide an accurate accounting of ‘the water rights it holds on a Tribe’s behalf.”).

- 71Id. at 593.

- 72Id. at 598–99.

- 73See id. at 599.

- 74See id. at 566–67 (majority opinion).

- 75See id. at 599 (Gorsuch, J., dissenting).

- 76See id. at 566–67 (majority opinion).

- 77See Leslie Sanchez et al., Beyond “Paper” Water: The Complexities of Fully Leveraging Tribal Water Rights, Fed. Rsrv. Bank Minneapolis (May 3, 2023), https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2022/beyond-paper-water-the-complexities-of-fully-leveraging-tribal-water-rights [https://perma.cc/Y5AZ-GY3X].

- 78See Navajo Nation v. DOI, No. 3:03-cv-00507 (D. Ariz. Mar. 14, 2003); Anna Smith et al., Supreme Court Keeps Navajo Nation Waiting for Water, ProPublica (Jun. 26, 2023, 2:00 PM), https://www.propublica.org/article/supreme-court-navajo-nation-water-rights-scotus [https://perma.cc/76VP-K9FR].

- 79See Patty Ferguson-Bohnee, How the Native American Vote Continues to be Suppressed, Am. Bar Ass’n (Feb. 9, 2020), https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/voting-rights/how-the-native-american-vote-continues-to-be-suppressed/ [https://perma.cc/WZ7E-963Y].

- 80See Jaclyn Diaz, U.S. Congress Reaches a Milestone in Indigenous Representation, NPR (Sep. 20, 2022, 5:00 AM), https://www.npr.org/2022/09/20/1123295313/congress-indigenous-representation-mary-peltola [https://perma.cc/7N8T-XHPG].

- 81See Charles V. Stern, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R44148, Indian Water Rights Settlements 1 (2023).

- 82See Enacted Indian Water Rights Settlements, U.S. Dep’t Interior (Jan. 2023), https://www.doi.gov/siwro/enacted-indian-water-rights-settlements [https://perma.cc/DVB6-BG7Y].

- 83See Historic Water Rights Settlement for Navajo Nation and Colorado River Tribes Moves Forward, CPR (May 24, 2024), https://www.cpr.org/2024/05/24/historic-water-rights-settlement-for-navajo-nation-and-colorado-river-tribes-moves-forward/ [https://perma.cc/8ZKQ-P9KH].

- 84Stern, supra note 81, at ii.

- 85See id. at 10.

- 86See id. at 14.

- 87See id. at 16.

- 88See id. at 15.

- 89Id.

- 90Leslie Sanchez et al., Paper Water, Wet Water, and the Recognition of Indigenous Property Rights, 10 J. Ass’n Env’t & Res. Economists 1545, 1545 (2023); see also Mick Kulikowski, Study: Tribal Water Rights Underutilized in U.S. West, N.C. State Univ. (Apr. 19, 2023), https://news.ncsu.edu/2023/04/tribal-water-rights-underutilized-in-u-s-west/ [https://perma.cc/ YG8R-EJXK].

- 91See Sanchez, supra note 90, at 1576.

- 92Addressing the Urgent Needs of Our Tribal Communities: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on Energy and Commerce, 116 Cong. 1 (2020) (Statement of Jonathan Nez, President of Navajo Nation).

- 93Id. at 13–14.

- 94See id. at 13–16.

- 95See Interior Department Announces Actions to Protect Colorado River System, Sets 2023 Operating Conditions for Lake Powell and Lake Mead, U.S. Dep’t Interior (Aug. 16, 2022), https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/interior-department-announces-actions-protect-colorado-river-system-sets-2023 [https://perma.cc/4WRT-7ME5].

- 96See Hollie Silverman et al., Navajo Nation Surpasses New York State for the Highest Covid-19 Infection Rate in the US, CNN (May 18, 2020, 5:55 PM), https://www.cnn.com/2020/ 05/18/us/navajo-nation-infection-rate-trnd/index.html [https://perma.cc/3GWY-K77C].

- 97See id.

- 98CDC Off. Readiness & Response, Global Preparedness: Disease Knows No Borders 1 (2023).

- 99See Nat’l Intel. Council, NIE-2022-02480, National Intelligence Estimate: Economic and National Security Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic Through 2026 i, 1 (2022).

- 100See Fact Sheet: Vice President Harris Announces Action Plan on Global Water Security and Highlights the Administration’s Work to Build Drought Resilience, White House (June 1, 2022), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/06/01/fact-sheet-vice-president-harris-announces-action-plan-on-global-water-security-and-highlights-the-administrations-work-to-build-drought-resilience/ [https://perma.cc/YE9C-U3MU].

- 101Id.

- 102See Exec. Order No. 14,008, 86 Fed. Reg. 7,619 (Feb. 1, 2021).

- 103Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad, The White House (Jan. 27, 2021), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/27/executive-order-on-tackling-the-climate-crisis-at-home-and-abroad/ [https://perma.cc/QXL8-453R].

- 104Id.

- 105See id.

- 106See id.

- 107See Patrick J.D. Griffin, Note, An Overview of Federal Emergency Powers, 15 N.Y.U. J.L. & Liberty 859, 870–71 (2022).

- 108See id. at 900.

- 109See A Guide to Emergency Powers and Their Use, Brennan Ctr. for Just. (Feb. 8, 2023), https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/guide-emergency-powers-and-their-use [https://perma.cc/3J23-PSB8].

- 110See id.

- 111See id.

- 112See id.

- 113Id.

- 114See 42 U.S.C. § 5170.

- 115The Stafford Act defines “major disaster” as any “natural catastrophe . . . in any part of the United States, which in the determination of the President causes damage of sufficient severity and magnitude to warrant major disaster assistance under this chapter to supplement the efforts and available resources of States, local governments, and disaster relief organizations.” Id. § 5122(2).

- 116Id. § 5122(1).

- 117See Griffin, supra note 107, at 903.

- 118Mark P. Nevitt, Is Climate Change a National Emergency?, 55 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 591, 618 (2021).

- 119See Declared National Emergencies Under the National Emergencies Act, Brennan Ctr. for Just. (Aug. 17, 2023), https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/declared-national-emergencies-under-national-emergencies-act [https://perma.cc/U9XE-FLNT].

- 120977 F.3d 853 (9th Cir. 2020), vacated sub nom. Biden v. Sierra Club, 142 S. Ct. 56 (2021) (reflecting changed circumstances casting doubt on need for further proceedings without discussion of the President’s authority under the NEA).

- 121See id. at 890.

- 122See id. at 864 (stating that “[t]he NEA empowers the President to declare national emergencies”).

- 123See Nevitt, supra note 118, at 625 (“Regardless of emergency definitions proposed by scientists, scholars, statutes, or courts, Congress has chosen not to define the term within the NEA, effectively delegating this decision to the President.”).

- 124See Griffin, supra note 107, at 863; see also Nevitt, supra note 118, at 620 (emphasizing four aspects of emergencies: they are unforeseeable, grave, involve a government response, and require an unforeseeable response).

- 12542 U.S.C. §§ 2000e–2000e-17.

- 126See Harris v. Forklift Systems, Inc., 510 U.S. 17, 23 (1993).

- 127Id.

- 128See Erbest B. Abbott & Erin J. Greten, Representing States, Tribes, and Local Governments Before, During, and After a Presidentially-Declared Disaster, 48 Urb. Law. 489, 498 (2016).

- 129See id.

- 130See United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, FCCC/TP/2012/7, Slow Onset Events (2012).

- 131See Abbott & Greten, supra note 128, at 491.

- 132See id.

- 133See Diane P. Horn et al., Cong. Rsch. Serv., IN11696, Climate Change, Slow-Onset Disasters, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency 2 (2021).

- 134See Abbott & Greten, supra note 128, at 547.

- 135See id.

- 136See 42 U.S.C. § 5133.

- 137See Arizona v. Navajo Nation, 599 U.S. 555, 566–67, 599 (2023) (majority opinion and Gorsuch, J., dissenting).

- 138See Emergency Powers: Overview, supra note 18.

- 139See infra Figure 1.

- 140See Elizabeth M. Webster et al., Cong. Rsch. Serv., R46326, Stafford Act Declarations for COVID-19 FAQ 16 (2020).

- 141Overview of Stafford Act Support to States, FEMA, https://www.fema.gov/pdf/emergency/nrf/nrf-stafford.pdf [https://perma.cc/UPS6-HLAZ].

- 142See L. Elaine Halchin et al., Cong. Rsch. Serv., IN11972, Presidential Declaration of Climate Emergency: NEA and Stafford Act 1 (2022).

- 143See id. at 1–2.

- 144See id. at 3.

- 145See Declared National Emergencies Under the National Emergencies Act, 1978-2018, supra note 104.

- 146See 50 U.S.C. § 1621(b) (referencing these subsequent “provisions of law conferring powers and authorities to be exercised during a national emergency”).

- 147See A Guide to Emergency Powers and Their Use, supra note 94.

- 148See id.

- 149See 50 U.S.C. §§ 1701–1707.

- 150§ 1701(a).

- 151Nevitt, supra note 118, at 631.

- 152See Mark P. Nevitt, On Environmental Law, Climate Change, and National Security Law, 44 Harv. Env’tl L. Rev. 321, 356–58 (2020) (arguing for the creative application of various NEA authorizing provisions in the context of addressing the climate crisis); see also Nevitt, supra note 118, at 625–42.

- 153Griffin, supra note 107, at 909.

- 154See Jean Su & Maya Golden-Krasner, Ctr. For Biological Diversity, The Climate President’s Emergency Powers: A Legal Guide to Bold Climate Action from President Biden 40 (2022).

- 155See Greten & Abbott, supra note 128, at 498.

- 15642 U.S.C. § 5122(2).

- 15742 U.S.C. § 5122(1).

- 158See Horn et al., supra note 133, at 2.

- 159See Chris Mooney & Shannon Osaka, Is Climate Change Speeding Up? Here’s What the Science Says, Wash. Post (Dec. 26, 2023), https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2023/12/26/global-warming-accelerating-climate-change/ [https://perma.cc/B7JM-MQED].

- 160See Drought in Numbers 2022—Restoration for Readiness and Resilience, Relief Web (May 12, 2022), https://reliefweb.int/report/world/drought-numbers-2022-restoration-readiness-and-resilience [https://perma.cc/K657-M564].

- 161See Virginia Iglesias et al., Recent Droughts in the United States are Among the Fastest-Developing of the Last Seven Decades, 37 Weather & Climate Extremes 1, 4 (2022); see also Fast-Onset Droughts are Accelerating, Coop. Inst. for Rsch. in Env’t Scis., Univ. CO. Boulder (Sept. 1, 2022), https://cires.colorado.edu/news/fast-onset-droughts-are-accelerating [https://perma.cc/ 9NBB-BZE2].

- 162See Xing Yuan et al., A Global Transition to Flash Droughts Under Climate Change, 380 Science 187, 187–191 (2023).

- 163See 42 U.S.C. § 5122(1).

- 164See id. (defining “emergency” as “any occasion or instance for which, in the determination of the President, Federal assistance is needed to supplement State and local efforts and capabilities to save lives and to protect property and public health and safety, or to lessen or avert the threat of a catastrophe in any part of the United States.”).

- 165See Diane P. Horn, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R46989, FEMA Hazard Mitigation: A First Step Toward Climate Adaptation i (2022).

- 166Su & Golden-Krasner, supra note 154, at 43.

- 167See Horn, supra note 165, at 7–8.

- 168Id. at 6–7.

- 169See id. at 4.

- 170See FEMA, Drought Mitigation: Hazard Mitigation Policy Aid 1 (2023).

- 171See id. at 3.

- 172See id.

- 173See Su & Golden-Krasner, supra note 154, at 45.

- 174See Anna E. Normand et al., Cong. Rsch. Serv., R47383, Federal Assistance for Nonfederal Dam Safety 13 (2023).

- 175Su & Golden-Krasner, supra note 154, at 45.

- 176Horn et al., supra note 133, at 2.

- 177See Su & Golden-Krasner, supra note 154, at 46.

- 178See Chris Currie, Gov’t Accountability Office, GAO-18-443, Implementation of the Major Disaster Declaration Process for Federally Recognized Tribes 19–20 (2018).

- 179See id. at 19.

- 180L. Elaine Halchin et al., Cong. Rsch. Serv., IN11972, Presidential Declaration of Climate Emergency: NEA and Stafford Act 2 (2022).

- 181See Elizabeth M. Webster & Bruce R. Lindsay, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R41981, Congressional Primer on Responding to and Recovering from Major Disasters and Emergencies 1–2 (2023).

- 182L. Elaine Halchin et al., Cong. Rsch. Serv., IN11972, Presidential Declaration of Climate Emergency: NEA and Stafford Act 2 (2022).

- 183See Elizabeth M. Webster & Bruce R. Lindsay, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R41981, Congressional Primer on Responding to and Recovering from Major Disasters and Emergencies 2 (2023).

- 184See Christina E. Wells, Katrina and the Rhetoric of Federalism, 26 Miss. Coll. L. Rev. 127, 127 (2007).

- 185See id. at 128.

- 186See Going With The Flow: Water’s Role in Global Migration, World Bank (Aug. 23, 2021), https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2021/08/23/going-with-the-flow-water-s-role-in-global-migration [https://perma.cc/R4QC-WYK4].

- 187Wells, supra note 184, at 128.

- 188Sandy Recovery Improvement Act, Pub. Law No. 113-2, 127 Stat. 4 (2013).

- 189See Disaster Declarations for Tribal Nations, FEMA (Feb. 26, 2021), https://www.fema.gov/data-visualization/disaster-declarations-tribal-nations [https://perma.cc/ 6WF9-QY9A].

- 190FEMA Releases First-Ever National Tribal Strategy, FEMA (Aug. 18, 2022), https://www.fema.gov/press-release/20220818/fema-releases-first-ever-national-tribal-strategy [https://perma.cc/2CQV-4JZN].