The Shifting Law of Sexual Speech: Rethinking Robert Mapplethorpe

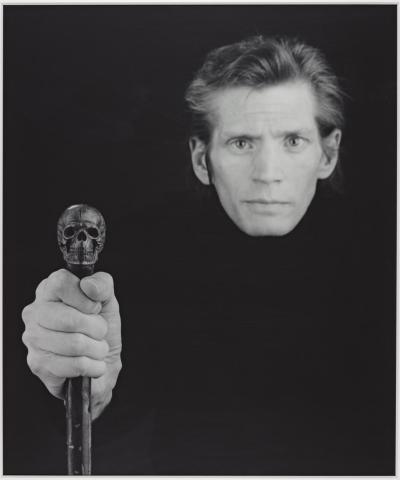

Robert Mapplethorpe, Self-Portrait (1988), Tate Modern

Introduction

This Article explores the dramatic changes that have occurred over the last thirty years in the First Amendment doctrines governing sexual speech. As a prism through which to evaluate these changes, I consider the thirtieth anniversary of the landmark Robert Mapplethorpe trial, the first censorship prosecution against an art museum in the history of this country and the defining battle in the culture wars that roiled post-Reagan America. The target was the exhibition of formally beautiful, sexually hard-core photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe on view at a museum in Cincinnati. The controversy that erupted over those images—fueled by anxieties about AIDS, homosexuality, sadomasochism, race, government funding for the arts, and the vanishing boundary between art and pornography—spilled out of the courtroom into popular culture and into the halls of the United States Congress.

This Article looks back at this landmark art trial and establishes its continuing relevance for free speech law. What emerges is a surprising story about dramatic changes in the major First Amendment rules governing sexual speech. In particular, I look at the shifting trajectories over the years of the two legal doctrines that were at the center of the Mapplethorpe case—obscenity law and child pornography law—and I show the radically divergent paths these two areas of law have taken. While obscenity law has receded in importance, and while the allegedly obscene photos from the trial have become widely accepted in museums and in the art market, child pornography law has followed the opposite course. In contrast to the allegedly obscene pictures, which pose almost no legal risk today, the two photographs of children that were on trial have become more, not less, controversial over the past thirty years, to the point where curators are quietly reluctant to show these images at all. In my view, these photos now occupy a space of legal and moral uncertainty.

In recent years there has been a growing art world “obsession” with Robert Mapplethorpe.1 Three major museums have staged retrospectives of Mapplethorpe’s work in the past few years.2 Once denounced on the floor of the U.S. Senate, his work viewed as menacing and contagious, Mapplethorpe has now emerged as a market and museum darling, to the point where a critic recently declared that the art world had been gripped with a case of “Mapplethorpe fever.”3 The once-taboo photos that were on trial for obscenity have now become prized in museums and in the art market. Yet in spite of this fever, and the easy acceptance of the pictures that were once charged with violating obscenity law, the two images of children from the trial have quietly receded from view, and their legal status has become more fragile than it once was.

What happened to change the dynamics of showing these works, legally and culturally? And what explains the differing trajectories of the two major doctrines governing sexual speech? The trial marked the last gasp of obscenity law, which has since become legally inert. Yet child pornography law has expanded dramatically over the same period. In tracing the divergent paths taken by these two doctrinal areas, three themes emerge: First, I show the direct relationship between obscenity law’s decline and child pornography law’s ascent. Second, I explore the shift within free speech law about what kinds of harms should be legally cognizable. Both obscenity law and child pornography law are premised on notions of harm that are anomalous within First Amendment doctrine. Yet over the last thirty years, the diffuse notion of harm that animated obscenity law has been eclipsed by the concrete vision of harm that undergirds child pornography law: harm baked into the production of the material itself. Finally, I argue that shifting cultural norms in the wake of the Mapplethorpe trial have had a profound impact on First Amendment law, even as the law has affected those norms. Free speech law governed this chapter in the culture wars, yet in surprising ways, the changing social norms unleashed by the culture wars have also governed free speech law.

Part I explores Mapplethorpe’s artistic process and legacy and tells the story of the nation-wide scandal that erupted around his work, culminating in the landmark 1990 trial. In Part II, I argue that a combination of AIDs panic, racism, and homophobia, as well as backlash against the changing role of art in society, made Mapplethorpe a perfect target for prosecution during the culture wars of the 1980s and 1990s. I then analyze why, in spite of all these factors that made Mapplethorpe the perfect target, the prosecution nonetheless led to an acquittal. Here I argue that certain artistic aspects of the work made Mapplethorpe surprisingly easy to defend under obscenity doctrine. Part III analyzes the prosecution of two photographs of nude children included in the exhibition; I argue that these photographs now occupy a space of greater legal and cultural uncertainty than they did thirty years ago. Part IV argues that a fundamental mistake about artistic meaning underlay the Mapplethorpe’s court’s pronouncements on the photographs as well as common legal assumptions about the stability of artistic meaning. I conclude that the dramatic changes in free speech law discussed in this Article have been inextricably intertwined with and influenced by the battles over social norms that the Mapplethorpe controversy unleashed.

I. Scandal and the Landmark Art Trial

A. The Story of Mapplethorpe

Intertwined with Mapplethorpe’s legal legacy is a rich artistic and cultural narrative. Mapplethorpe provoked political controversy, polarized critics, broke boundaries in the history of art and photography, and paved the way for a new generation of artists working today.4 Formally perfect, sometimes radical in content, the work continues to capture the attention of curators and collectors long after Mapplethorpe’s death from AIDS in 1989 at age 42.

1. The artist’s work

Mapplethorpe’s mature photographic work fell into three main categories: nudes, still lifes (particularly of flowers), and portraits. The work that provoked Congress and prosecutors was a subset of nudes that Mapplethorpe called the “sex pictures”;5 he also called them “smut art.”6

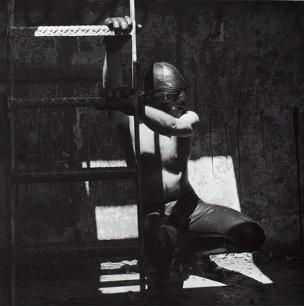

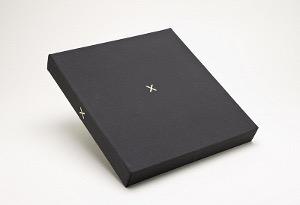

The initial sex pictures were taken in a period from 1977–1980 and depicted the gay male S&M community Mapplethorpe was actively participating in at the time, when he frequented New York clubs like the Mineshaft.7 Mapplethorpe initially collected these images into a portfolio of thirteen photos called the X Portfolio. These photographs, some of them showing hard-core, radical sex acts (as I will describe below), were rarely exhibited in the U.S. during Mapplethorpe’s life, even as his fame grew. The photos were often segregated from his main body of work despite Mapplethorpe’s attempt to integrate them into the corpus of his art.8 For example, in one of their few showings during the artist’s life, the sex pictures were displayed at the downtown avant-garde art space, the Kitchen, while the same month in 1977, the more polished Holly Solomon Gallery held an exhibit of Mapplethorpe’s regal and uncontroversial portraits.9

Robert Mapplethorpe, Jim, Sausalito (X Portfolio) (1977), the J. Paul Getty Museum

Robert Mapplethorpe, X Portfolio (1978), the J. Paul Getty Museum

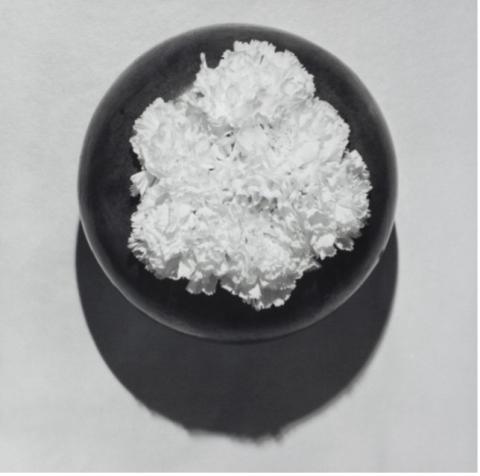

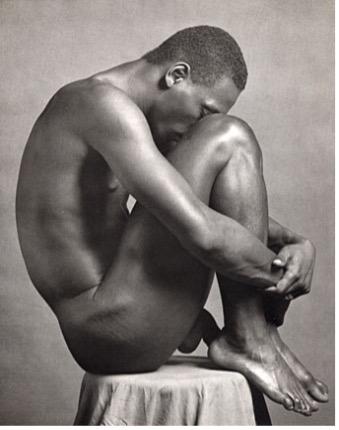

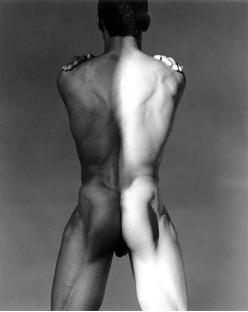

The companion to the X Portfolio, produced at the same time, was another collection of thirteen photos called the Y Portfolio. (Portfolio collections in photography are a traditional method of assembling a compendium of an artist’s work.) The Y Portfolio contained Mapplethorpe’s elegant, stylized pictures of flowers. Accompanying these two was a third collection of thirteen photographs called the Z Portfolio, which Mapplethorpe put together in 1981. It was comprised of images of nude Black men, some of whom Mapplethorpe was artistically and sexually involved with.10

Mapplethorpe, Carnation, N.Y.C. (Y Portfolio) (1978)

Mapplethorpe, Leigh Lee, N.Y.C. (Z Portfolio) (1980)

Mapplethorpe wanted the three portfolios ideally exhibited “all in one mass”;11 in this way he highlighted the formal similarities between the jarringly distinct subjects.12 In Cincinnati, where five of the X Portfolio pictures led to obscenity charges, the X, Y, and Z Portfolios were displayed together in a grid like format.13

Mapplethorpe’s career soared in the late 1980s at roughly the same time he grew ill from AIDS. A one-man show of his work opened in July 1988 at the Whitney Museum of American Art, marking a new level of status and visibility in his career. That same year, a retrospective of his work called The Perfect Moment was organized by the Institute of Contemporary Art (“ICA”) at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Opening in December 1988, it was set to travel to six more venues, including Cincinnati, from 1989 to 1990.14 On March 9, 1989, Mapplethorpe died of AIDS at age 42.

2. The funding debates

Two months after Mapplethorpe’s death, politicians in the U.S. Senate began an attack on the National Endowment for the Arts (“NEA”) for its funding of controversial art. The initial focus was on another scandalous artist, Andres Serrano. Serrano’s work Piss Christ was a picture of a crucifix submerged in the artists’ urine. Serrano had been awarded a $15,000 prize by the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art in North Carolina, which had received funding in part from the NEA.15 Conservative members of Congress and an activist evangelical group, the American Family Association (headed by the Reverend Don Wildmon), led the charge against the NEA for its funding choices.

In June 1989, shortly after Congress began its attack on the NEA, and only a few months after Mapplethorpe’s death, The Perfect Moment (the traveling Mapplethorpe retrospective that had originated at the University of Pennsylvania’s ICA) was scheduled to open in Washington, D.C. at the Corcoran Gallery of Art. But in a startling act of self-censorship, the director of the Corcoran cancelled the show—after all the invitations had gone out—citing the escalating political debates about art in Congress. Presumably the Corcoran curator was worried about congressional attention because the ICA had received $30,000 from the NEA to support the exhibition and its catalogue.16 As is frequently the case with acts of self-censorship, the Corcoran’s decision to cancel the show only served to draw further attention to Mapplethorpe’s work.

Brandishing Mapplethorpe’s virtuosic and frankly sexual pictures before Congress, conservative Senator Jesse Helms seized the moment.17 Helms pointed repeatedly to Mapplethorpe’s supposed “promotion of a homosexual lifestyle” and his death from AIDS. Although they defeated Helms’s more radical proposal, an outraged Congress nonetheless amended the statutory rules governing NEA grants to deny funding to “obscene” art; the law was later struck down as unconstitutionally vague.18 After this legal defeat, Congress tried again, this time amending the statute governing NEA grants to add a so-called “decency rule.”19 The new language, upheld by the Supreme Court in NEA v. Finley,20 was passed in direct response to the Mapplethorpe and Serrano controversies. It provided that in its grant-making decisions, the NEA should take “into consideration general standards of decency and respect for the diverse beliefs and values of the American public.”21 Mapplethorpe had become the poster child for what conservatives claimed was a culturally elite art world that mocked American values.22

3. The trial

It was in this hostile political climate that The Perfect Moment was set to open in Cincinnati at the Contemporary Arts Center (“CAC”). Amidst political pressure, the museum sought to steel itself against attack; it segregated any general federal funds it received from the Mapplethorpe show, placed warning signs for visitors, and did not admit anyone under 18 to the exhibition.23 Approximately 80,000 people saw the show.24 On March 22, 1990, the CAC sought a declaratory judgment that the work was not obscene. The show opened on April 7, 1990 and was met on its first day with a grand jury indictment. Mapplethorpe was dead, but the museum and its director, Dennis Barrie, were charged with violating obscenity law as well as an Ohio law prohibiting nude depictions of children. Seven of the show’s 175 pictures were on trial.25 Barrie faced up to one year in jail.26

The prosecution’s main case was to present the photos and the testimony of three police offers who established that the photos were displayed at CAC. The defense presented four days of expert testimony, largely from art critics and curators.27 After a jury trial, the defendants were acquitted.28 The trial gripped the art world, turning Mapplethorpe into a cause célèbre and a symbol of the threat posed by the culture wars to artistic and sexual freedom.29

B. “Mapplethorpe Fever”:30 The Resurgent Interest in the Work

There has been a resurgence of interest in Mapplethorpe in recent years. A younger generation of curators has engaged with his legacy, and his status as an art market star has risen. Over the last few years critics have chronicled the art world’s “growing obsession” with the artist.31 One critic declared that the art world has been gripped with a case of “Mapplethorpe fever.”32 Vogue Magazine termed it “Mapplethorpe mania.”33 Certainly museums have been lavishing attention on his work. Two major museums recently collaborated on a joint retrospective of Mapplethorpe’s oeuvre; Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium spanned both the J. Paul Getty Museum and LACMA (the Los Angeles County Museum of Art).34 A documentary about his work and the scandal surrounding it debuted to critical acclaim in 2016.35 The Guggenheim staged a major one-year, two-part Mapplethorpe retrospective in 2019.

Mapplethorpe’s star is also rising in the art market. An image from the X Portfolio broke a new auction record for that series in 2015.36 The auction was for one of his most controversial—and highly regarded—explicit images, Man in a Polyester Suit, depicting the artist’s lover, Milton Moore, wearing a three-piece suit with his penis exposed and his head unseen. This image, once denounced in Congress, sold for $478,000.37 (The photograph was one of an edition of fifteen.) The last time the work sold publicly was in 1992, when it brought $9,000.38

II. Does Obscenity Law Still Matter?

Until Mapplethorpe, there had never been an obscenity prosecution against an art museum in the history of this country. Obscenity law was haunted by the specter of having banned great works of literature, but never significant works of art. In its first obscenity decision in 1957, Roth v. United States,39 the Supreme Court entered with some trepidation a doctrinal arena marked by a history of literary philistinism. Prior to the Court’s intervention, lower courts had overseen the suppression (and, later, the eventual freeing) of acclaimed books such as James Joyce’s Ulysses and D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover.40 Writing his concurrence in Roth, the Court’s first foray into the field, Chief Justice Warren evoked obscenity law’s historic suppression of “great” cultural works,41 referring to the “[m]istakes of the past.”42

And indeed, those mistakes had become a thing of the past by the time the Mapplethorpe case came to trial in 1990. Although the Supreme Court had struggled mightily during the years between its first major obscenity decision and its last in 1973,43 its goal had been to ban “‘hard-core’ pornography”44 while at the same time protecting works of cultural import.45 By 1973, when the Court finally agreed on the modern definition of obscenity, it looked as if it had settled on a formula that achieved both goals and that would ward off another cultural embarrassment. Then came Mapplethorpe.

The current definition of obscenity, crafted by the Court in 1973 in Miller v. California, allows the government to ban material only if the work, taken as a whole and according to contemporary community standards:46

(a) “appeals to the prurient interest;”

(b) “depicts [sexual conduct] in a patently offensive way . . . ; and”

(c) “lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.”47

All three prongs must be met before a work can be held obscene and thus banished from First Amendment protection. This means that no matter how sexually explicit—even disgusting—it may be, if a work possesses “serious . . . artistic . . . value,” it is protected.48 Although one might presume this standard would protect automatically any work displayed in a major U.S. museum, that presumption turned out to be wrong.

The Mapplethorpe case marked the return of obscenity law’s repressed history of banning works of cultural value, the very problem that modern obscenity jurisprudence was designed to combat.49 What was it about Mapplethorpe’s work that destabilized the Court’s project? And what was it about Mapplethorpe that led to a new chapter in this history of cultural attacks, provoking the first obscenity trial against an art museum in the history of the U.S.?

The answer has to do with the nature of Mapplethorpe’s work and the dramatic changes in the meaning of “art” that it signaled. But it also has to do with a problem that had been brewing undetected in obscenity law for some time: its fundamental clash with a sweeping shift that was taking place in art.

A. Mapplethorpe’s Scandalous Subject Matter

First consider the obvious reason why Mapplethorpe’s work provoked this unprecedented trial: some of his images were so controversial and provocative, particularly for their time, that the prosecution seemed preordained. Mapplethorpe depicted sadomasochistic, sometimes violent, hard-core sex acts between gay men. For example, one of the prosecuted pictures showed a man fisting another man, his hand and wrist inserted into the other’s anus. Another picture depicted a leather-clad man urinating into the mouth of another man, who kneels to accept it. Even by today’s standards, thirty years later, in which pornography,50 not to mention homosexuality,51 have become comparatively mainstream, some of the S&M pictures are hard to look at.52 One Mapplethorpe picture, for example, not included in the Cincinnati exhibit, depicts a bleeding penis (after having been grazed by a knife), clamped in a bondage device.53

But in contrast to how we see them today, these images carried a radically different meaning thirty years ago. They were shown at the height of the AIDS crisis and the “culture wars”54 that were raging in post-Reagan America. Homophobia and AIDS panic were rampant. Homosexual sodomy was criminal, with the Supreme Court’s approval.55 Gay men were politically reviled as they were being ravaged by an epidemic. Panic over the possibility that one could be contaminated just by touching gay men was so great that police sometimes wore rubber gloves during AIDS activist protests.56 Conservative writer William F. Buckley had argued that people with AIDS should be mandatorily tattooed.57 Mapplethorpe had died from AIDS a year before the exhibition opened in Cincinnati; he documented his illness in his art.58 And his work was received as if the pictures themselves were polluted with the contaminating threat of the disease. As critics have noted, “the spectre of death” hung over the photos; “the information that Mapplethorpe died of AIDS [was] always available.”59 Members of Congress continually spoke of Mapplethorpe’s disease as they denounced funding for his work. Senator Helms, for example, calling Mapplethorpe’s work “homosexual pornography,” said Mapplethorpe “died of AIDS while spending the last years of his life promoting homosexuality.”60

Further adding fuel to the fire, the works were tinged with the frisson of interracial sex. Many of Mapplethorpe’s most famous portraits were of eroticized, nude Black men; some photos depicted interracial couples. Senator Helms highlighted the interracial theme in his attack on Mapplethorpe. Helms denounced a picture (that did not exist, oddly, other than in his imagination) of “two males of different races” in an erotic pose “on a marble-top table” as evidence of the artist’s depravity.61 (In Part IV, infra, I turn directly to the complex issue of race in Mapplethorpe’s work.)

Though the heady combination of race, homosexuality, pornography, AIDS-panic, and violent sadomasochistic practices was already enough to provoke controversy, an additional factor upped the ante: the fact that the photos were presented in highly classicized style and displayed with the imprimatur of “art” in a museum made them even more galling to conservative critics. Indeed, as explained above, the photos helped launch a national debate about government funding for the arts. Congress found in Mapplethorpe a perfect symbol of what it viewed as the perverse, menacing art world, thumbing its nose at mainstream values.

Thus it’s hard to imagine a more perfect target for prosecutors wishing to win an obscenity prosecution in 1990: an unpopular speaker, targeted by Congress as a contagious pervert, whose work depicted unpopular practices that tapped into national dread, hatred, and paranoia. As explained above, under the Miller standard for obscenity, a conviction under obscenity law requires a prosecutor to prove three prongs.62 The first two prongs seem like no-brainers for a win against these images in 1990 America (in a conservative Midwestern city no less). Under the first prong, the government must prove that a work appeals to the “prurient”—meaning “shameful or morbid”—interest.63 Under the second prong of Miller, the government must show that the work is “patently offensive” according to “contemporary community standards.”64 Both inquiries seem designed to suppress representations of sexual practices that deviate from the mainstream—and perfectly tailored for Mapplethorpe. For example, in discussing the meaning of prurience, the Supreme Court had previously let stand a lower court interpretation that defined prurience as the opposite of “a good, old-fashioned, healthy” interest in sex.65 Prurience thus depends on a dichotomy between “shameful or morbid” desire on the one hand, and “good old-fashioned, healthy” sexuality on the other. In 1990 America, it seems clear that Mapplethorpe’s sex pictures would have fallen on the wrong side of that line.

Indeed, the defense all but conceded that it would lose on the first two prongs of the Miller test.66 The case seemed like an easy win for the prosecution. Mapplethorpe’s work was a perfect lightning rod for the sexual and cultural tumult that was sweeping America. But there was a third prong of the test that would prove pivotal to the case: was Mapplethorpe’s work “serious art”?

B. The Clash between Obscenity Law and Postmodern Art

Beyond the almost ludicrously controversial subject matter of the work for its time, I believe there was another reason the prosecution of Mapplethorpe’s work was preordained. In my view, the crisis of Mapplethorpe was built into the structure of obscenity law itself and its clash with a dramatic change in artistic practice that had been brewing, unnoticed, as the Court crafted its modern definition of obscenity in 1973. Obscenity law was built on the very assumption that contemporary artists like Mapplethorpe had begun to question as a central tenet of their work: that there was a distinction between pornography and art. The fusion of pornography and art that Mapplethorpe championed was not a peripheral practice but instead central to a deeper transition in art that was underway just as Miller was decided.

The Miller standard for obscenity law, discussed above, had diminished the constitutional protection the Court had afforded art in its previous obscenity cases. The Court’s prior obscenity test (upheld by only a plurality) had protected any work, no matter how filthy, prurient, or offensive, unless it was “utterly without redeeming social value.”67 This was the famous language that had protected the novel Fanny Hill in 1966.68 Miller rejected this expansive test in favor of a standard that protected less art and was easier for the prosecution to meet.69 A work of art now needed to possess “serious artistic value” to gain protection. As Justice Brennan noted in his dissent to Miller’s companion case, Paris Adult Theatre I v. Slaton:

The Court’s approach necessarily assumes that some works will be deemed obscene—even though they clearly have some social value—because the State was able to prove that the value, measured by some unspecified standard, was not sufficiently “serious” to warrant constitutional protection. That result is . . . an invitation to widespread suppression of sexually oriented speech.70

The problem is that this legal retrenchment occurred at a radical turning point in the history of art: the rise of “postmodernism.” The changes in art that were brewing at the time of Miller would ultimately render the new standard even less protective of art than Justice Brennan had feared.71 This is because the “serious artistic value” test etched in stone the precise standard against which art was beginning to rebel in 1973. As I have argued elsewhere and as I explain below, Miller was premised on the reigning, but soon to crumble, vision of art in mid-century America, the period called “Modernism.”72

Miller’s protection only for art that demonstrated “serious value” would have made perfect sense in mid-century America. As I have argued, a particular form of modernism, “late modernism,” which had triumphed in the 1950s and 1960s, was foundational to Miller. 73 It may be hard for us in our era of critical and artistic pluralism to imagine the cultural penetration once attained by one artistic school of thought.74 But in mid-century America, late modernism, particularly as articulated by its leading critic, Clement Greenberg, was so dominant that a recent scholar described Greenberg as having ruled the mid-century art world with a “papal authority.”75

The period of late modernism as articulated by Greenberg (and his peers) was a purist movement.76 Greenberg believed that art could “maintain its past standards of excellence”77 by using the “characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself—not in order to subvert it, but to entrench it more firmly in its area of competence.”78 Late modernism distinguished between good art and bad art by demanding that good art be pure, self-critical, original, sincere, and serious.79

The standard of “serious artistic value” seems perfectly designed to protect the art we most valued in the late modernist era. As an art critic wrote of modernism, “the highest accolade that could be paid to any artist was this: ‘serious.’”80 It is as if the word “serious” were a code word for modernist values: critics consistently equate it with the modernist stance.81 In fact, the very foundation of Miller, the belief that some art is just not good enough or serious enough to be worthy of protection, mirrors the modernist notion that distinctions could be drawn between good art and bad, and that the value of art was objectively verifiable.82

Yet the Court devised the Miller test for “serious artistic value” in 1973, precisely the time that modernism in art was entering its death throes. Miller represented one of the last gasps of this crumbling but still powerful modernist zeitgeist. One year earlier, the art critic Leo Steinberg had been perhaps the first to apply the name “post-modernism” to the revolutionary shift in art that was emerging just as Miller was decided.83 The emerging postmodern ethos took aim at each of the Greenbergian precepts I catalogued above. Artists attacked basic modernist distinctions: between good art and bad, between high art and popular culture, between the sanctity of the art context and real life. Artists not only questioned the modernist demand that art be “serious,” many made work that also questioned the idea that art must have any traditional “value” at all.

One of many ways that artists attacked these assumptions was to incorporate pornography into their art. The introduction of this debased vernacular into the realm of high art disrupted the modernist norms that undergirded the serious artistic value standard. In some ways, this disruption was the essence of Mapplethorpe’s practice. He insisted “I can make pornography art.”84 Mashing up “fine art photography and the commercial sex industry,” Mapplethorpe was “scrambling aesthetic categories and genres” that had previously been understood to be “mutually exclusive.”85 According to one critic, this was the major contribution of Mapplethorpe’s work: his incorporation of the pornographic led to a “redrawing of the boundary line of the aesthetic to include that which had previously been excluded from it.”86 By making what he called “smut art,” his work undermined the foundation on which the Miller test and obscenity law were founded: that we can separate the pornographic from the artistic and valuable.

C. Why Art Won: An Assessment

How on earth did the Mapplethorpe defense win given all this? Mapplethorpe’s shocking subject matter rendered prongs one and two of the Miller test forgone losers. Prong three, protecting works of “serious artistic value,” depended on the precise late modernist view of art that Mapplethorpe’s work challenged.

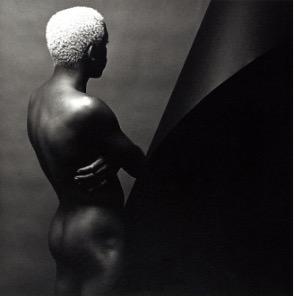

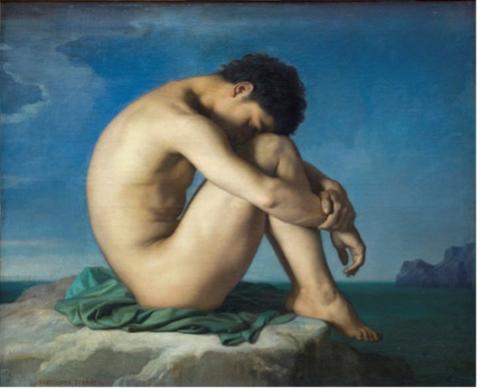

Yet, surprisingly, while certain characteristics of his photography made Mapplethorpe an inevitable obscenity law target thirty years ago, other qualities of his work help explain why the prosecution resulted in an acquittal. Indeed, I want to assert that in some ways, the Mapplethorpe case was easy to defend. In spite of his shocking subject matter, on a formal level, Mapplethorpe’s work looked thoroughly and undeniably like art. In fact, it was conventional, even old-fashioned. He was an accomplished and elegant photographer. Formally beautiful, rich with art historical allusions to the classical tradition (from Greek sculpture to Caravaggio to nineteenth century portraiture), his meticulously printed work highlighted his classicized use of light and composition.87

(The images below give a glimpse of these qualities.) Calling attention to their formal artistry, the photographs are tasteful, even traditional; his use of black and white (rather than the popular color photography at the time) signaled restrained classicism and old-fashioned assumptions about what art was meant to look like. At the time, street photography like Gary Winogrand’s had captured the attention of critics, in contrast to Mapplethorpe’s more traditional staged studio photographs.88

It was easy to describe Mapplethorpe’s photos as “art”—if you stopped looking at the subject matter and looked only at their formal qualities.89

Hippolyte Flandrin, Study (1835-6)

Mapplethorpe, Ajitto (1981)90

Mapplethorpe, Jim (1980)

Contrast his work with other artists from the same era who were also disrupting the boundaries between obscenity and art. For example, consider Karen Finley, a later target of the culture wars, who brought the Supreme Court challenge to the very NEA amendments that Congress had passed in response to the Mapplethorpe scandal.91 In contrast to Mapplethorpe, Finley produced performance art that may have been hard to categorize as “art” at all, particularly for a generation accustomed to paintings and sculpture as the paradigmatic art forms. Famously smearing her nude body with yams, screaming about sex acts, performing in art venues but also bars, Finley dispensed with traditional markers of “art.” A signature Finley piece was called Yams Up My Granny’s Ass.92 Compared to Finley’s art, Mapplethorpe’s work was formally traditional and even conservative; its shock derived from the tension between its high art presentation and its untraditional content.

Karen Finley Performance

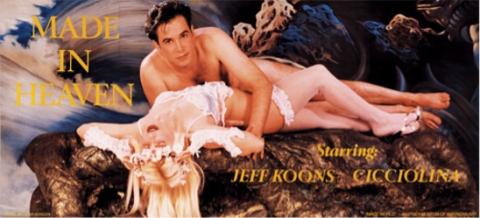

Or consider Jeff Koons’s merger of art and porn, his Made in Heaven series from 1989 that was exhibited in New York shortly after the Mapplethorpe trial. In some ways, Mapplethorpe’s work strikes me as easier to defend on an obscenity charge than Koons’s would have been if challenged at the time. In contrast to Mapplethorpe’s work, Made in Heaven used the vernacular of porn without any trappings of art. Koons produced the series by posing with his then-wife, the porn star Cicciolina. The images of the couple were shot not by the “artist” but by Cicciolina’s usual porn photographer, using the sets and the accoutrements of porn, complete with lurid, tacky backdrops. Like much of Koons’s art, the work looked garish, kitschy, and lowly; it reveled in its lack of conventional markers of high art.93

And, like Mapplethorpe’s, the work included hard-core images, such as a close up of anal sex. Of course, though some of the work was hard-core, Koons was still more insulated from prosecution or conviction than Mapplethorpe in the sense that he was engaging in heterosexual sex acts—with his wife no less. Even so, the work still has the capacity to shock; in the 2014 retrospective of Koons’s work, the Whitney displayed this series (other than the billboard, pictured below) in a separate room from the rest of the exhibition, complete with warning signs about its content.

Jeff Koons, Made in Heaven (1989)

Thus, compared to other artists who were incorporating sex into their work at the time, I think Mapplethorpe’s work was relatively easy to defend under Miller’s third prong. The old-fashioned formalism of Mapplethorpe’s work, coupled with obscenity law’s requirement of “serious . . . artistic . . . value” explains the sometimes laughable testimony that emerged at the trial. In my experience, contemporary art world professionals sometimes seem perplexed by the tenor taken by some experts for the defense in 1990.94 For example, consider the almost ludicrously formalist testimony of Janet Kardon, the curator who had organized the Mapplethorpe show for the ICA. Describing Mapplethorpe’s self-portrait with a bullwhip inserted into his anus, Kardon ignored the sexual content, testifying about its “classical” composition by focusing on the placement of the horizon line.95 When asked to comment on another photographs from the X Portfolio, depicting a finger shoved into a man’s penis, Kardon said, “It’s a central image, very symmetrical, a very ordered, classical composition.”96 Symmetry and composition are not exactly the first things one thinks about when viewing this image. A critic at the time called such testimony “disingenuous.”97 A more recent critic labelled Kardon’s emphasis on formal qualities of the work “bizarre.”98 But Kardon’s peculiar testimony was rooted directly in the requirements of the Miller test, and in the truth of Mapplethorpe’s classicized work. That classicism, plus Mapplethorpe’s rising fame and emerging blue-chip museum status, made his case relatively easy to defend under Miller, at least compared to many of his peers, who were defying the standard of serious artistic value in a way that made their work seem almost unrecognizable as “art.”

D. The Decline of Obscenity Law

How significant a threat is obscenity law to art in a post-Mapplethorpe world? Not very—for two reasons. First, as I will explain, obscenity law has all but died as a prosecutorial tool.99 Second, and relatedly, the merger between art and pornography that Mapplethorpe and his compatriots championed has receded as a theme in contemporary art.

In the 1990s, for a number of reasons I have explored elsewhere, obscenity law began to fall into relative disuse.100 One main reason obscenity was all but abandoned was that child pornography was viewed as the far more pressing problem. Under the Clinton administration, as public concern about child sexual abuse escalated, the Child Exploitation and Obscenity Unit of the Department of Justice chose to focus its limited resources on child pornography rather than obscenity.101

Since that shift, the decline in obscenity prosecutions—and the explosion of adult pornography it both responded to and facilitated—have made it hard to reverse course and to put the pornography genie back in the bottle. In our porn-soaked contemporary culture, a pornographer’s defense is built into obscenity law’s reliance on community standards: the government in an obscenity case must prove that the material exceeds contemporary community standards.102 Yet given the sea of pornography in which we live (a condition created in part by the decline of obscenity law), it is now much harder for a prosecutor to prove that material on trial deviates in its prurience and patent offensiveness from the kind of stuff everyone else in the community has been watching. Perhaps this is why when the Bush administration’s Department of Justice revived obscenity law in the early 2000s,103 it tended to target extremely hard-core pornography on the fringes of the industry, material that might seem to a jury to be unlike the usual pornographic fare they or their neighbors had grown accustomed to.104 In any event, the Bush revival of obscenity law was quietly put to bed by the Obama administration, which (like Clinton’s) devoted its resources to child pornography rather than adult obscenity cases.105 Nonetheless, as I have documented, obscenity law is still invoked sometimes to fills the gaps for other doctrinal areas.106 And although there has been a resurgence of conservative political rhetoric against pornography, there have been few prosecutions.107 Most would be unwinnable in my estimation because the pornographic culture in which we now live will present a significant hurdle for prosecutors pursuing obscenity convictions.

The second reason that obscenity law is less of a threat to art than it once was has to do with related developments in art. The merger of porn and art that Mapplethorpe pioneered, once a scandalous assault on the modernist demarcation between art and non-art, high and low, has become so commonplace as to be dull, even old-fashioned. Artist John Currin, in an interview about a recent exhibition with its de rigueur blend of art, appropriated images and hard-core pornography, explained his use of porn by saying: “It’s not a shock tactic. In every art school in the world there’s a guy doing porn. As a failed shock tactic, that’s kind of interesting to me.”108

Of course, there’s still a lot of sex in museums and galleries; at times it has seemed almost normative. And I still get an occasional call, perhaps once every few years, from a museum that is worried about sexual content that might cross the line, at least enough to invite controversy if not prosecution. (By contrast, the calls I get from institutions or artists with concerns about other kinds of offensive art, or about the possible reach of child pornography law, are more frequent.) And some of the sexually infused art on view these days is so graphic that I assume any law review would be uncomfortable reproducing it, even in a scholarly article, just as mainstream newspapers like the New York Times still do not reproduce some of Mapplethorpe’s renowned works.109 But even so, it’s hard to think of any sexually explicit art work in our porn-saturated world that has the power to shock us as Mapplethorpe once did.

I do not want to discount entirely the possibility that the next sexual outlaw/artist could fall prey. The Mapplethorpe case shows us that we should worry about the risk of selective prosecution of an under-enforced law against an unpopular speaker.110 It is commonplace to say that in our current era, the chances of being prosecuted for obscenity are like the chances of being struck by lightning.111 But as Mapplethorpe shows, the chances of being struck are not random; politically and sexually unpopular speakers seem particularly attractive.

Nonetheless, to the extent art thrives on transgression, in a post-postmodern, post-Mapplethorpe world, when it comes to porn, there is not much left to transgress. While Mapplethorpe and other artists once pioneered the dissolution of the art/porn boundary, many artists take this dissolution for granted and have simply moved on. Because of changes in art and culture, and related changes in legal enforcement, obscenity law poses a far less significant threat to art institutions today than it did thirty years ago.

III. Child Pornography Law and Art: A Growing Issue for Museums and Galleries

In contrast to the allegedly obscene pictures, which seem far less scandalous by today’s standards than they were in 1990, Mapplethorpe’s A Perfect Moment included two photographs that have become much more, not less, controversial over the past thirty years, to the point where curators are quietly reluctant to show these images at all. Both pictures are child nudes and raise the specter of child pornography. In one, called Jesse McBride, a young boy poses naked, perched on a chair next to a refrigerator. In the other, called Rosie, a four-year-old girl sits on a stone bench. She wears a dress, but her legs are bent in a way that reveals she is wearing no underpants. She gazes unsmilingly, at the camera, her face conveying perhaps curiosity, perhaps wariness. To the extent it’s relevant, the mothers of both children were friends with Mapplethorpe and arranged the photo shoots.112 As adults, both children looked back with pride on the photos.113 McBride called the picture of himself “angelic.”114

These pictures occupy a space of legal and cultural uncertainty. They have become harder to show over the years, both in terms of the cultural controversy they might provoke, but also because their legal status has become more fragile over time. Indeed, I believe a museum that displays these pictures today is taking on a risk (very small but not impossible) of prosecution. As I will explain below, as a matter of First Amendment law, I think these pictures ought to be protected, but the law governing this area is so subjective and unpredictable that I cannot say with certainty that they would be protected if prosecuted. That these images have not been targeted owes more to prosecutorial discretion—the reluctance to pursue an art museum115 —than to legal clarity.

The legal status of these two images stands in stark contrast to that of the five pictures of adult S&M gay sex that were prosecuted in Cincinnati, which have become far less legally and culturally risky over the elapsed thirty years; they are all but certain to be protected given the current state of obscenity law that I described above. Indeed, the adult sex pictures prosecuted in Cincinnati were featured prominently in the recent major museum retrospectives of Mapplethorpe’s work at the Getty, LACMA, and the Guggenheim.116 But the curators for these shows conspicuously omitted the two child images.117 Curators have grown increasingly uncomfortable with these photographs. And, as with other photographic child nudes by other artists, the pictures have quietly disappeared from some museum websites as well. In recent years, at least two arts institutions have taken down two other photographer’s pictures of children based on threats of prosecution.118 In my view, given the evolution of child pornography law in the lower courts, the doctrine’s vast uncertainty, and the severe penalties that accompany a mistaken interpretation of it, this growing reluctance to show these kinds of art images may be a defensible, if extremely risk-averse, legal position.

What explains this trajectory? What happened to change the dynamics of showing these works, legally and culturally? Once again, the answer points to a story about the mutually productive relationship between censorship law and culture.

A. Thirty Years Later: The Dramatic Expansion of Child Pornography Law

In 1990, when Mapplethorpe’s child pictures were shown in Cincinnati, child pornography law was in its infancy. Born in 1982, child pornography law developed at a time when child sexual abuse had only recently come to light in the late 1970s as a widespread cultural crisis.119 Child pornography law grew up in a pre-digital era that barely resembled our present one, in which digital and technological advances have allowed the production and distribution of horrific child abuse images to skyrocket.120 As the crisis of child pornography has grown, child pornography law has emerged as a complex, rapidly growing, and deeply anomalous area of First Amendment jurisprudence.121 Just as obscenity law began its decline, child pornography law grew to fill the gap. The body of law that has developed since New York v. Ferber,122 the Court’s first child pornography case, has made the Mapplethorpe child images shown in Cincinnati more vulnerable to prosecution now than they were thirty years ago.

Child pornography law began in 1982 with the Supreme Court’s decision in Ferber, in which it encountered a novel First Amendment problem: whether non-obscene123 sexual depictions of children—speech not falling into any previously defined First Amendment exception—could be constitutionally restricted.124 The Court’s answer was “yes.” Although the Ferber Court announced five reasons that supported the exclusion of child pornography from First Amendment protection,125 the fundamental focus of these rationales was this: child pornography must be prohibited because of the grievous harm done to children in the production of the material.126 The creation of child pornography requires an act of child sexual abuse. The opinion repeatedly emphasizes this concern for the abuse “of children engaged in [the] production” of child pornography. 127 Indeed, the Court framed the issue as whether “a child has been physically or psychologically harmed in the production of the work.” 128

When it comes to artistic expression, this urgent rationale animating child pornography law—to protect real children from abuse entailed in creating the materials—leads to a pivotal distinction between this area and obscenity law: unlike obscenity law, child pornography law makes no explicit exception for works of “serious . . . artistic . . . value.”129 Whereas obscenity law was initially premised on the worthlessness of certain expression,130 child pornography law excludes speech from First Amendment protection because of the horrible abuse from which it stems. This explains why the Court’s jurisprudence in this area departs so dramatically from obscenity law: the merit of an artwork is irrelevant to the child who has been abused. As the Court explained, even if a work possesses serious value, that “bears no connection to whether or not a child has been harmed in the production of the work.”131 Thus, the only argument that led to the acquittal of the adult sex pictures at the Mapplethorpe trial—the serious artistic value defense—is irrelevant under child pornography law.132 Furthermore, unlike obscenity law, child pornography law does not require us to evaluate works as a whole, a standard which is more speech protective, as described above.133

Meanwhile, the legal definition of child pornography has grown increasingly capacious over the last thirty years in the lower courts.134 “Child pornography” is defined as “visual depictions” of “sexual conduct involving a minor.”135 Federal law defines “sexually explicit conduct” as “(A) sexual intercourse . . . ; (B) bestiality; (C) masturbation; (D) sadistic or masochistic abuse; or (E) lascivious exhibition of the genitals or pubic area of any person” under 18.136 The inclusion of this latter category—“lascivious exhibition of the genitals”—as part of the class of prohibited depictions of “sexually explicit conduct” introduces the most problematic aspect of defining child pornography. How should courts discern the difference between a criminally “lascivious” image and an acceptable image of a child, such as an innocent family photo? The Court has made clear that nudity is not the dividing line between protected speech and lascivious child pornography. Indeed, the Ferber Court stated that “nudity, without more is protected expression.”137 Conversely, and surprisingly, a picture can be criminalized as “lascivious exhibition of the genitals” even if it contains no nudity, even if the child’s genitals are not discernible,138 and even if it contains no sexual conduct.139

The Supreme Court has so far offered no guidance on the question of what constitutes a “lascivious exhibition of the genitals” or what differentiates such an image from constitutionally protected images of children, nude or otherwise. In the absence of any guidance, and as the onslaught of horrific child sexual abuse images has grown exponentially over the years, lower courts have been busily filling the gap left open by the Supreme Court. As I have documented in recent work, the result is a growing body of law that has rendered the category of child pornography increasingly subjective at its edges.140

Indeed, many lower courts now evaluate whether a picture is lascivious based not on what happened to the child at issue but on whether a pedophilic viewer might find the picture arousing.141 This allows for the possible prosecution of pictures that were not the product of abuse but still appeal to a deviant audience. In this way, the definition of child pornography has come unmoored from its constitutional rationale—that the pictures lack First Amendment protection because their production requires abuse.142

The leading case on the meaning of “lascivious exhibition” is United States v. Dost,143 a 1986 California federal district court case that announced a six-part test for analyzing images. The Dost test, followed by virtually all state and lower federal courts,144 identifies six factors that are relevant to the determination of whether a picture constitutes a “lascivious exhibition”:

(1) whether the focal point of the visual depiction is on the child’s genitalia or pubic area;

(2) whether the setting of the visual depiction is sexually suggestive, i.e. in a place or pose generally associated with sexual activity;

(3) whether the child is depicted in an unnatural pose or in inappropriate attire, considering the age of the child;

(4) whether the child is fully or partially clothed, or nude;

(5) whether the visual depiction suggests coyness or willingness to engage in sexual activity;

(6) whether the visual depiction is intended or designed to elicit a sexual response in the viewer.145

The test does not require that all factors be met to find that a depiction is a lascivious exhibition.146 Indeed, one circuit court suggested that satisfying merely one of the six factors would suffice to criminalize a photograph as child pornography.147

B. Are the Mapplethorpe Pictures Protected Speech?

What would the result be today for the Mapplethorpe pictures described above, Jesse McBride and Rosie? Would a federal prosecution succeed? In my view, the answer is unclear. (Given this uncertain status, I have not included the pictures here for the reader to assess.) On my analysis of the images, in light of the way courts have interpreted the Dost factors, I offer a few impressions. First, if merely one Dost factor is required, then certainly factor four, which asks if the child is nude, is met. Furthermore, both pictures might be seen as having a focal point on the child’s pubic area as well, thereby meeting both factors four and one of the test. Justice Brennan argued that this focal point inquiry can be easily manipulated. In elaborating on what he found to be the constitutional vagueness of a similar provision of a state law, Justice Brennan wrote in dissent, “the test appears to involve nothing more than a subjective estimation of the centrality or prominence of the genitals in a picture or other representation. Not only is this factor dependent on the perspective and idiosyncrasies of the observer, it also is unconnected to whether the material at issue merits constitutional protection.”148 The subjective nature of this inquiry was on full display during the Mapplethorpe trial, when the prosecutor had the following exchange on the subject with a defense witness, discussing the picture of Jesse McBride:

“Isn’t the focus primarily between the legs of the child, the penis area?” [the prosecutor] Prouty pursued.

“Mr. Prouty, I don’t have that reading of the direction of the lines” Stein responded.

“Could anyone?” Prouty said.

Defense attorney Marc Mezibov objected. “The only person that seems to have that reading is Mr. Prouty,” he said.149

Although I doubt that either Mapplethorpe image is in a “sexually suggestive” setting under factor three, I note that this factor can be subject to surprising interpretations; for example, courts have divided on whether a bathroom is a sexually suggestive setting.150 In a First Circuit case, the government argued, unsuccessfully (and in my view quite startlingly) that a beach was a sexually suggestive setting because “many honeymoons are planned around beach locations.”151 This kind of subjective analysis can affect the interpretation of all the factors, not just the third. And the subjectivity is significantly heightened in those jurisdictions where courts require the material be viewed through the imagined subjective vision of the pedophile voyeur when applying the factors.152

There are significant arguments to be made for the defense of these pictures. First is the most obvious: these pictures, taken with their parents’ approval, depict children being children, playing and cavorting in an utterly non-sexual way that is more akin to a photo in a family album. To read them as sexual seems perverse. The picture of Rosie, for example, was taken (with her mother’s consent) at a weekend wedding celebration at her house in northern England.153 Jesse’s mother explained that the picture of her son was taken at her apartment while she was there and that her son was naked because he had just taken a shower.154 The circumstances under which these photos were taken seem worlds away from the horrors of sexual abuse that child pornography law is designed to prohibit (and that, unfortunately, the vast amount of child pornography images portray). At trial, a local art critic had testified that the pictures were “most innocent and nonsexual,” comparing them to Renaissance cherubs or “modern-day angels.”155 Both children pictured looked back on these images with pride when they were adults.156 Specifically, I would point to the sixth Dost factor, as weighing heavily in favor that they were not designed to arouse an erotic reaction by the viewer.157

Nonetheless, this argument does not guarantee the photographs’ protection. First, remember that a Dost conviction does not require that all factors or even the majority of them be met, and in my view at least two could arguably be met here. Second, there are counterarguments to be made under the sixth factor. In particular, to counter the claim that the work was not designed to arouse an erotic reaction in the viewer, one could point to the very merger between art and pornography that Mapplethorpe championed in his adult sex pictures. It’s also possible to argue that the camera angle in the Rosie photograph, positioned as if to see up the child’s dress, could be seen as sexual, particularly to a pedophile viewer.158 Furthermore, I might worry about a recurrence of the kind of sinister prejudice that entered the debates about Mapplethorpe in Congress during the time of the exhibition, when members of Congress suggested a link between Mapplethorpe’s homosexuality and a pedophilic intent. For instance, a congressman from California said that Mapplethorpe “was a child pornographer. He lived his homosexual, erotic lifestyle and died horribly of AIDS.”159

I do not interpret these pictures as sexual, nor do I interpret them as the product of child sexual abuse. Yet given the current state of child pornography law, I am not certain that the pictures would be protected by a court applying the Dost test. Ultimately, my analysis points to a conflict between the expansive reach of the Dost test and the underlying rationale of child pornography law itself, to protect children from the abuse that the production of child pornography necessarily entails.160

C. Why the Pictures Won

What saved the pictures in 1990? The answer stems from two features of the Ohio law at issue in the Mapplethorpe trial. Although that law had potentially sweeping aspects,161 it was far more generous to defendants than federal child pornography law in two important respects.162

First, the Ohio law made an exception for parental consent, an exception that federal law does not provide (and indeed, one that may be ill-advised given the unfortunate reality that many children are abused by their own family members).163 The mothers of both children, Jesse and Rosie, signed affidavits and testified expressing their approval of the images; these affidavits figured as an affirmative defense to the charges.164

The second feature of the Ohio law that was more generous to defendants than the First Amendment requires was a provision to allow exceptions for work “presented for a bona fide artistic . . . purpose.”165 As I indicated previously, the Supreme Court has made clear that the defense of artistic value is not a mandatory feature of child pornography law. Of course, states are free to make laws that are more speech-protective than the Constitution requires, and Ohio’s law, by carving out a sphere for artistic works, did so in this respect.

Thus, the fact that these images were exonerated in 1990 does not settle their legal status today if they were prosecuted. The Mapplethorpe defense was able to invoke two idiosyncratic speech-protective features of Ohio law that depart from what the Supreme Court has indicated is required by the First Amendment. Neither issue would be relevant in a federal prosecution.

IV. How Meaning Shifts: The Relevance for First Amendment Law

One of the most revealing aspects of the Mapplethorpe case was a ruling issued by the Court that addressed the nature of artistic meaning.166 The Court’s analysis exposed a clash that reverberates to this day between legal and artistic views on how to assess the “meaning” of art.

The issue arose in the context of a ruling on a pretrial motion in limine filed by the state of Ohio on a key aspect of obscenity law. Since 1957, in Roth v. United States,167 the U.S. Supreme Court made it a requirement of obscenity law that a work be evaluated “as a whole.” The previous approach that Roth replaced had been far less protective of artistic expression; it allowed prosecutors to focus on isolated passages of a work,168 plucking out of a novel only the naughty bits. Yet while Roth’s new “work as a whole” standard was relatively easy to apply to works of literature—the unit of measurement is the whole book—the Mapplethorpe trial raised a question of first impression for a court: what constitutes the “work as a whole” for an art exhibit? Is it the entire exhibit? Or is each individual picture a “work as a whole” in its own right? The question ultimately implicates the relationship between meaning and context.

In the Mapplethorpe case, this question was potentially pivotal: The five S&M sex pictures on trial, extremely graphic, appeared in a larger exhibition of 175 works dominated by G-rated, tasteful portraits and still lifes. Indeed, the curatorial installation of the X Portfolio was calculated to challenge the assumption that the sexual works could be viewed apart from their context. As explained above, the sex pictures were displayed in a grid, mixed with the Y Portfolio’s elegant flowers. The arrangement invited the viewer to consider the sex pictures’ unity with the other works. In this way, the exhibition was curated to illustrate a central tenet of Mapplethorpe’s photographic project. As the artist explained in his own words: “When I’ve exhibited pictures, I’ve tried to juxtapose a flower, then a picture of a cock, then a portrait, so that you could see they were the same.”169

Yet the Court rejected the contention that a work’s meaning could depend on its context. It ruled instead that each picture was a work as a whole in its own right. In elaborating on this ruling, the judge offered a stark vision of how images produce meaning. The judge wrote, “the pictures speak for themselves . . . . The click of the shutter has frozen the dots, colors, shapes, and whatever finishing chemicals necessary, into a manmade instant of time. Never can that ‘moment’ be legitimately changed.”170

Note two assumptions undergirding this statement. First, the court assumes that the image is a self-contained universe that requires no interpretation—it “speaks for itself.”171 This is a longstanding—and problematic—theme in the history of the legal treatment of images in both First Amendment law and also other legal realms.172 As I have argued in previous work, this assumed ability of images to “speak for themselves” helps explain the systematic suspicion that images are not fully “speech” for purposes of the First Amendment, and the greater free speech protection afforded verbal as opposed to visual forms of representation.173 Rebecca Tushnet has documented a similar problem in copyright law, where courts frequently view images as so transparent that they need no interpretation.174

Second, the court’s analysis is built on the assumption that a work’s meaning cannot vary: it is “frozen” in the “instant of time” it was created.175 The analysis pictures the meaning of a photograph as eternally bound to its moment of creation, so that it can’t fluctuate over time or across different contexts. As the court wrote, “never can that moment be legitimately changed.”176 This view—that visual images have a “frozen,” static and unchanging meaning—has had a stranglehold on legal analyses of art, not only in First Amendment law177 but also in other doctrinal areas, as I have previously explored.178

The fallacy of this legal assumption is particularly evident in the changing racial meanings that have been ascribed over the years to Mapplethorpe’s works. Earlier I discussed Mapplethorpe’s photographs of Black men. I argued that anxieties about race and interracial desire had fueled the conservative outrage over Mapplethorpe in 1990 America. Of course, there is no First Amendment doctrine under which these photographs of Black men could be prosecuted for their racial content alone. Obscenity law filled the gap.

At the same time that conservatives feared these pictures, some Black critics, artists, and curators of the 1980s and 1990s explored the disturbing racial politics of Mapplethorpe’s images of Black males, criticizing Mapplethorpe’s fetishization and objectification of the Black male body. At the same time, however, there were champions of the work, who saw it as having an activist potential to subvert rather than reinforce racial stereotypes.179

I believe that in the thirty years since the Mapplethorpe trial, the racial component of Mapplethorpe’s work has grown more inescapable to us as viewers, even eclipsing the sexual content of the work, which has become comparatively more mundane. As our society has increasingly grown aware of the troubling implications of mainstream depictions of race and Blackness, I believe that Mapplethorpe’s Black males may make us even more uncomfortable than they once did, in contrast to Mapplethorpe’s S&M images, which time has to some extent tamed.180 In this way, we see that even though the pictures have stayed the same, the lens through which we view the pictures has shifted, bringing new meanings to the fore.

Ironically, the story of Mapplethorpe’s work, from the time of its creation to present, demonstrates the folly of the court’s approach to meaning. Instead of showing us that the meaning of his images were “frozen” in the “instant of time” they were created and that meaning can “never” change, we see instead a proliferation of fluctuating meanings that the works have evoked. The X Portfolio photographs were taken in the late 1970s when AIDS was unknown; Mapplethorpe was documenting his world of sexual experimentation in a time without fear of the still-undiscovered virus that was brewing as the photographs were taken. But after Mapplethorpe’s death, and in the hands of conservative critics, the work came to stand for the threat posed by AIDS and by homosexuality to American culture. Conversely, to the political left, Mapplethorpe’s work came to stand for artistic freedom.181

None of these interpretations had any basis in the moment of the works’ creation. They all arose in the history of its use and reception. And over the ensuing years since the trial, Mapplethorpe’s meanings have continued to change. We see the work differently now, as attitudes about homosexuality, pornography, sexuality, child sexual abuse, race, and art have all changed.

The story I have told about the works’ shifting legal status bears testament to its evolving meaning. Our changing cultural perspective not only reflects but also informs the legal shifts I have described, as the works have become more vulnerable to one legal doctrine and less vulnerable to another. Therefore, to understand how misguided the court was in its assessment of how art produces “meaning,” we can look at the changing legal status of Mapplethorpe’s art over the last thirty years. The history of Mapplethorpe’s work, from its moment of creation to its present reception, bears witness to the way in which art’s “meaning,” rather than “frozen,” evolves over time and across contexts. Ultimately these evolving meanings informed the shifting legal status of Mapplethorpe’s art.

Conclusion

The Mapplethorpe trial, fueled by anxieties about AIDS, homosexuality, sadomasochism, pornography, race, government funding for the arts, and the vanishing boundary between art and smut, was the defining battle in the culture wars of post-Reagan American. As I have argued, it also marked a turning point in the First Amendment doctrines governing sexual speech. The trial marked the first obscenity prosecution against an art museum in the history of this country. But since that time, obscenity law has receded in importance and the once-scandalous, allegedly obscene photos from the trial have become widely accepted in museums and in the art market. Child pornography law has followed the opposite course. In contrast to the allegedly obscene pictures, which pose almost no legal risk today, the two photographs of children that were on trial have become more, not less, controversial over the past thirty years, to the point where curators are quietly reluctant to show these images at all. In my view, these photos now occupy a space of legal and cultural uncertainty. Ultimately my account shows how these dramatic changes in free speech law have been inextricably intertwined with and influenced by the battles over social norms that the Mapplethorpe trial unleashed.

- 1See Rain Embuscado, Forthcoming Book of His Archive Adds to Recent Robert Mapplethorpe Fever, Artnet News (Feb. 9, 2016), https://news.artnet.com/art-world/robert-mapplethorpe-archive-published-422789 [https://perma.cc/C2VF-LUP3].

- 2See Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium, J. Paul Getty Museum, http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/mapplethorpe/ [https://perma.cc/N3P2-2546] (last visited Mar. 25, 2020) (website for Getty show); Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium, Los Angeles Cty. Museum of Art, https://www.lacma.org/art/exhibition/robert-mapplethorpe-perfect-medium [https://perma.cc/X5JK-D457] (last visited Mar. 27, 2020) (website for LACMA show).

- 3Embuscado, supra note NOTEREF _Ref54601199 \h 1 08D0C9EA79F9BACE118C8200AA004BA90B02000000080000000D0000005F00520065006600350034003600300031003100390039000000 .

- 4See Paul Martineau & Britt Salvesen, Robert Mapplethorpe: The Photographs (Paul Martineau & Britt Salvesen eds., 2016). For an important analysis of the artistic significance of Mapplethorpe’s work, see Arthur C. Danto, Playing with the Edge: The Photographic Achievement of Robert Mapplethorpe (1996).

- 5Richard Meyer, Mapplethorped: Art, Photography, and the Pornographic Imagination, in Robert Mapplethorpe: The Photographs 231, 237 (Paul Martineau & Britt Salvesen eds., 2016).

- 6Kevin Moore, Whipping Up a Storm: How Mapplethorpe Shocked America, Guardian (Nov. 17, 2015), https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/nov/17/robert-mapplethorpe-the-perfect-moment-25-years-later [https://perma.cc/389U-ESNK].

- 7See Ryan Linkof, On the Edge, in Robert Mapplethorpe: The Photographs 55 (Paul Martineau & Britt Salvesen eds., 2016). The X Portfolio contained the earliest of the sex pictures, but Mapplethorpe continued to produce more.

- 8Meyer, supra note NOTEREF _Ref36385467 \h \* MERGEFORMAT 5 08D0C9EA79F9BACE118C8200AA004BA90B02000000080000000D0000005F00520065006600330036003300380035003400360037000000 ; see also Moore, supra note NOTEREF _Ref36385477 \h \* MERGEFORMAT 6 08D0C9EA79F9BACE118C8200AA004BA90B02000000080000000D0000005F00520065006600330036003300380035003400370037000000 .

- 9Id.

- 10These images were ultimately published in a book called the Black Book. Robert Mapplethorpe, Black Book (1988). For my discussion of the controversial racial politics of this work, see infra Part IV.

- 11Janet Kardon, Mapplethorpe Interview, in Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment 28 (2d ed. 1989).

- 12See Linkof, supra note NOTEREF _Ref36385846 \h \* MERGEFORMAT 7 08D0C9EA79F9BACE118C8200AA004BA90B02000000080000000D0000005F00520065006600330036003300380035003800340036000000 , at 56. As Mapplethorpe commented, “I don’t think there’s that much difference between a photograph of a fist up someone’s ass and a photograph of carnations in a bowl.” Parker Hodges, Robert Mapplethorpe: Photographer, Manhattan Gaze, Dec. 10. 1979–Jan. 6, 1980, at 5.

- 13Richard Meyer, The Jesse Helms Theory of Art, 104 October 131, 136 (2003). They were installed on a tilted table too high for small children to see on their own. Id.

- 14Martineau & Salvesen, supra note NOTEREF _Ref49857553 \h \* MERGEFORMAT 4 08D0C9EA79F9BACE118C8200AA004BA90B02000000080000000D0000005F00520065006600340039003800350037003500350033000000 , at 7.

- 15See Cynthia Carr, Going to Extremes, Village Voice, Nov. 20, 1990, at 67; Gregory B. Lewis & Arthur C. Brooks, A Question of Morality: Artists’ Values and Public Funding for the Arts, 65 Pub. Admin. Rev. 8 (2005).

- 16National Endowment for the Arts: A History, 1965–2008 93 (Mark Bauerlein & Ellen Grantham eds., 2009).

- 17Senator Helms denounced Mapplethorpe’s work as “filth” and “trash.” 135 Cong. Rec. S8807–08 (daily ed. July 26, 1989) (statement of Sen. Helms). See generally Owen M. Fiss, State Activism and State Censorship, 100 Yale L.J. 2087, 2092 (1991).

- 18Department of the Interior and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, Pub. L. No. 101–121, 304(a), 103 Stat. 701, 741 (1989), invalidated by Bella Lewitzky Dance Found. v. Frohnmayer, 754 F. Supp. 774, 781–82 (C.D. Cal. 1991). The NEA chose not to appeal the decision. Nat’l Endowment for the Arts v. Finley, 524 U.S. 569, 575 (1998).

- 1920 U.S.C. 954(d) (1994).

- 20524 U.S. 569 (1998) (rejecting a claim that the law was impermissible viewpoint discrimination and unconstitutionally vague). For discussion of Finley, see Lackland H. Bloom, Jr., NEA v. Finley: A Decision in Search of a Rationale, 77 Wash. U. L.Q. 1 (1999); Kristine M. Cunnane, Maintaining Viewpoint Neutrality for the NEA: National Endowment for the Arts v. Finley, 31 Conn. L. Rev. 1445 (1999); Cara Putman, National Endowment for the Arts v. Finley: The Supreme Court Missed an Opportunity to Clarify the Role of the NEA in Funding the Arts: Are the Grants A Property Right or an Award, 9 Geo. Mason U. Civ. Rts. L.J. 237, 242 (1999).

- 2120 U.S.C. § 954(d)(1) (1990).

- 22Robert Reid-Pharr, Putting Mapplethorpe in His Place, Art in Am. (Mar. 2016), https://www.gladstonegallery.com/sites/default/files/MAP-2016_03%20Art%20in%20America.pdf [https://perma.cc/LT66-HAK].

- 23Steven C. Dubin, Arresting Images: Impolitic Art and Uncivil Actions 184–85 (1992).

- 24Id.

- 25The five pictures that were alleged to be obscene were as follows: One shows a man urinating into another man’s mouth; another called Lou, N.Y.C. shows a finger inserted into a penis. Three more each depict a man with an object inserted in the rectum: a cylinder, a bull whip (this is a self-portrait), and a man’s fist and forearm. Fiss, supra note NOTEREF _Ref36385948 \h \* MERGEFORMAT 17 08D0C9EA79F9BACE118C8200AA004BA90B02000000080000000D0000005F00520065006600330036003300380035003900340038000000 at 2089 n.4.

- 26The CAC faced a $10,000 fine. Dustin Kidd, Legislating Creativity: The Intersections of Art & Politics 71 (2016).

- 27Dubin, supra note NOTEREF _Ref36385968 \h \* MERGEFORMAT 24 08D0C9EA79F9BACE118C8200AA004BA90B02000000080000000D0000005F00520065006600330036003300380035003900360038000000 , at 188–89.

- 28Mary T. Schmich, Art Gallery, Director Not Guilty: Cincinnati Jurors Clear Both of Obscenity Charges, Chi. Trib., Oct. 6, 1990, at 1; see also Sonya G. Bonneau, Ex Post Modernism: How the First Amendment Framed Nonrepresentational Art, 39 Colum. J.L. & Arts 195, 219 (2015).

- 29Paul Martineau & Britt Salvesen, Introduction, in Robert Mapplethorpe: The Photographs 1,7 (Paul Martineau & Britt Salvesen eds., 2016).

- 30Embuscado, supra note NOTEREF _Ref54601199 \h \* MERGEFORMAT 1 08D0C9EA79F9BACE118C8200AA004BA90B02000000080000000D0000005F00520065006600350034003600300031003100390039000000 .

- 31Id.

- 32Id.

- 33Julia Felsenthal, Mapplethorpe Mania Hits Los Angeles, Vogue (Mar. 16, 2016), https://www.vogue.com/article/robert-mapplethorpe-the-perfect-medium-interview [https://perma.cc/8L9V-CWLT].

- 34See J. Paul Getty Museum, supra note NOTEREF _Ref54602401 \h \* MERGEFORMAT 2 08D0C9EA79F9BACE118C8200AA004BA90B02000000080000000D0000005F00520065006600350034003600300032003400300031000000 ; Los Angeles Cty. Museum of Art, supra note NOTEREF _Ref54602401 \h \* MERGEFORMAT 2 08D0C9EA79F9BACE118C8200AA004BA90B02000000080000000D0000005F00520065006600350034003600300032003400300031000000 .

- 35James Poniewozik, Review: ‘Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures’ on HBO Gives Context to Controversy, N.Y. Times (Apr. 3, 2016), http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/04/arts/television/review-mapplethorpe-look-at-the-pictures-on-hbo-gives-context-to-controversy.html [https://perma.cc/5BVE-YUT6].

- 36The Sotheby’s sale marked “the first time in 23 years that one of the 15 images from the original edition of X Portfolio” came up at auction. Sarah Cascone, Robert Mapplethorpe’s Controversial ‘Man in Polyester Suit’ Photo Sells for $478,000, Artnet News (Oct. 8, 2015), https://news.artnet.com/market/robert-mapplethorpe-polyester-suit-sells-338631 [https://perma.cc/7JKN-N3KG].

- 37Daniel McDermon, Mapplethorpe Photograph Brings $478,000 at Auction, N.Y. Times: ArtsBeat Blog (Oct. 7, 2015, 3:26 PM), https://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/10/07/mapplethorpe-photograph-brings-478000-at-auction/ [https://perma.cc/E9DD-PUM3]. While this was the record for a work from Mapplethorpe’s X Portfolio, an earlier record for all of Mapplethorpe’s images was set at Christie’s in 2006, when his 1987 portrait of Andy Warhol sold for $643,200. See Stephen Milioti, Despite Record Prices for Photographs at This Year’s Auctions, it is Still Cheaper to Corner the Market in Leibovitz than Lichtenstein. Here’s How to Get Started, Fortune (Nov. 17, 2006), https://archive.fortune.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2006/11/13/8393128/index.htm [https://perma.cc/9RJJ-K267]. In 2017, a Mapplethorpe self-portrait sold for £450,000 (£548,750 with fees). Anna Brady, Auction Record for Mapplethorpe as Christie’s Introduces Two New Sales, Art Newspaper (Oct. 4, 2017), https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/christies [https://perma.cc/DRJ3-8WB7].

- 38Id.

- 39Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476 (1957). Prior to Roth, the Court had heard an obscenity case but split four-to-four and thus did not issue an opinion. The result was to affirm a state court obscenity judgment against noted critic Edmund Wilson’s novel, Memoirs of Hecate County. Doubleday & Co. v. New York, 335 U.S. 848 (1948). Thus, the Court was itself implicated in this history of failure. It had failed to protect a novel by one of the most prominent cultural critics of the day.

- 40See United States v. One Book Called “Ulysses,” 5 F. Supp. 182 (S.D.N.Y. 1933) (allowing the entry of Ulysses into the United States after previous censorship); Grove Press, Inc. v. Christenberry, 175 F. Supp. 488 (S.D.N.Y. 1959) (overturning, under the Roth standard, the Postmaster of New York’s suppression of Grove Press’s unexpurgated edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover).

- 41The Chief Justice wrote: “The history of the application of laws designed to suppress the obscene demonstrates convincingly that the power of government can be invoked under them against great art or literature, scientific treatises, or works exciting social controversy.” Roth, 354 U.S. at 495 (Warren, C.J., concurring in result). Cf. Frederick Schauer, Free Speech: A Philosophical Enquiry 178–79 (1982) (noting obscenity regulation’s history of plain errors in banning what we now consider great cultural works).

- 42Roth, 354 U.S. at 495 (Warren, J., concurring).

- 43Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15 (1973). Although it was a significant case in terms of its clarification of Miller’s third prong, the Court’s decision in Pope v. Illinois, 481 U.S. 497 (1987), did not change the basic definition or the rationale of obscenity law, both of which have remained in place since Miller and Paris Adult Theatre I v. Slaton, 413 U.S. 49, 97 (1973) were decided in 1973.

- 44The Court specified in 1973 that only “‘hard core’ pornography” should be banned under the obscenity test, Miller, 413 U.S. at 28, but failed to give a definition for the term. The phrase had appeared before in obscenity jurisprudence, including in Justice Stewart’s famous opinion stating that he understood obscenity law to encompass only “hard-core pornography.” Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S. 184, 197 (1964) (Stewart, J., concurring) (footnote omitted). Yet as for the definition of that phrase, he wrote, “I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced within that shorthand description, and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it . . . .” Id.