Speak Now: Results of a One-Year Study of Women’s Experiences at the University of Chicago Law School

The Women’s Advocacy Project (WAP) was a research project designed and run by law students at the University of Chicago Law School (“the Law School” or “UChicago Law”) during the 2017–2018 academic year—the first study of its kind to be conducted there.1 WAP collected data in an attempt to accumulate a rich and detailed set of information about women’s experiences at the Law School. WAP had four primary research components: classroom observations, achievement data collection, a student survey, and professor interviews. The project represents the efforts of over seventy law students. This article, written in the fall and winter of 2018, is a condensed version of WAP’s initial report. Readers interested in more detailed information about WAP’s methodology, findings, and recommendations should access the report at https://www.law.uchicago.edu/files/2018-05/wap_final.pdf.

WAP found significant differences between men’s and women’s experiences at the Law School, many suggesting that women still face considerable roadblocks and hurdles in legal education there. For example, women graduate with honors proportionately less frequently, participate voluntarily in class less, and are less likely to be satisfied with their law school experience than men. The data, however, also showed that women have made significant strides at the Law School.

WAP sought primarily to document and describe, but its initial report also offered recommendations responsive to the problems it identified. This article mentions some of those recommendations and suggests areas where further research is warranted.

I. Introduction

A. The Scope of the Project

The study was a starting point. WAP aimed to give members of the Law School community a wide range of information to spark conversations about gender issues and diversity more broadly and to lead the way for further research as well as reform. Despite WAP’s efforts to design a methodologically rigorous study, the information WAP was able to gather was inevitably incomplete in some ways. WAP had just one year to collect most of its data. WAP was only able to observe classes during one academic quarter, and given the subjectivity with which students experience classroom events, no classroom observation is likely to be perfect. In addition, WAP’s student survey captured students’ perspectives at one moment in time in their Law School careers. Although the participation rate was high, it is likely that some perspectives were not captured, and the information gathered was, of course, limited by the questions that WAP asked and that students were willing to answer. As with any survey, the WAP’s was vulnerable to common survey flaws, including selection bias. Professor interviews were similarly limited.

This study focuses on the University of Chicago Law School specifically. WAP endeavored to contextualize some of the findings and analysis throughout the report with available data about other law schools. Nevertheless, findings specific to UChicago Law should be useful regardless of whether identical information is available for other law schools. While many of UChicago’s peer schools struggle with similar issues surrounding diversity, WAP believes that the UChicago Law community should strive for gender equity not just comparatively but in absolute terms. In the findings and discussion presented below, WAP claims only to describe the situation at UChicago Law, unless comparative information about other schools is expressly provided.

More broadly, many of the gender disparities described in this report likely result at least in part from more general societal causes. Our primary purpose was not to evaluate whether the Law School is responsible for causing any particular gender disparity observed here; rather, the project attempted to generate information that might help to remedy those effects in the future.

Despite the fact that this study was a starting point for the UChicago Law community, it built upon an expansive body of research on gender in law school education.2 Specifically, the report was modeled on similar studies conducted at Harvard in 20043 and Yale in 2002 and 2012,4 which undertook research of a similar scope and had similar strengths and limitations. By all accounts, the Harvard and Yale studies led to positive impacts at both schools and were widely read. Many UChicago Law professors reported reading Yale’s 2012 study and adapting their teaching methods as a result of its findings. This study hopes to augment the contributions made by the earlier reports by shedding light on the current state of affairs at UChicago Law. Its aim was to spark conversations about how to improve the experiences of women at the Law School and how to promote their academic and extracurricular success.5

B. Information Limitations

In addition to the predictable methodological limitations described above, this report lacks other important categories of data that might have helped us interpret our primary findings.

First, although WAP requested aggregate grade data in various formats from the Law School administration, these requests were denied. The study therefore discusses different proxies for grades that indicate possible gender-based grade disparities at different points in students’ law school careers (such as Law Review membership, honors at graduation, etc.). None of these proxies are perfect, however.6 WAP also did not have access to admissions data, such as undergraduate GPA or LSAT scores; the Law School administration declined to share this information as well.

Second, WAP did not have information on the gender breakdown of the graduating classes from 2007–2012. The Law School Dean’s Office and Admissions Office provided WAP with the gender breakdown for each class for the 2013–2014 through the 2017–2018 academic years but denied requests to provide information for earlier years. As a result, although WAP was able to calculate the baseline gender composition of the 2014–2018 graduating classes, it was not able to do so for the earlier classes.7

Finally, WAP requested, but was not given, baseline data about the gender composition of each Law School course for the Autumn Quarter of 2017. To calculate the baseline gender composition of each class observed in the Classroom Observations component, WAP therefore relied on the class observers to report the gender breakdown of each class.

Though incomplete, WAP believes the findings in this report are a helpful starting point and is confident that they take advantage of all available information.

1. Note on other diverse identities

This study focused narrowly on the experiences of women at UChicago Law. It did not examine the experiences of students of color, LGBTQ students, or other groups of students who are likely to be underrepresented and who may face significant barriers to success at the Law School and in the legal profession (such as first-generation college students and students with disabilities). WAP acknowledges that there are often powerful intersections between different aspects of students’ identities. Many of the issues explored in this report likely impact students differently based on their race, religion, national origin, LGBTQ status, or other aspects of their identity, as well as the intersections of these characteristics. Many students and professors pointed this out in the student survey and during the professor interviews.

There were two primary reasons for WAP’s decision to focus almost exclusively on gender and not on the impact of other identity characteristics on student experience at the Law School. First, focusing on women’s experiences made the project more feasible in scope. WAP hopes that its methods enable other student groups to do similar research along different demographic lines in the future. Second, because of the small number of students of color at the Law School (and the small size of the school generally), it would have been much more difficult to report on findings based on race in an interesting or helpful way while preserving students’ and professors’ anonymity.

WAP is aware that most of the references to gender in this article are, unfortunately, binary. Although the goal of this report is not to re-entrench binary understandings of gender, almost all of our statistics are broken down with reference to women and men exclusively, and the report as a whole purports to evaluate the experiences of women at the Law School as compared to the experiences of men. Additionally, many of the methodologies employed in this study (described below) involved making assumptions about the gender of individuals that may have varied from those individuals’ self-defined identities. Focusing on the experiences of women, as opposed to students who may be trans, gender non-conforming, or who do not otherwise identify within binary understandings of gender was necessary for the purposes of this study because of similar concerns about scope, privacy, and anonymity to those described above.

We sincerely hope that future research will address those shortcomings and that our work will make that research easier.

II. Methodology

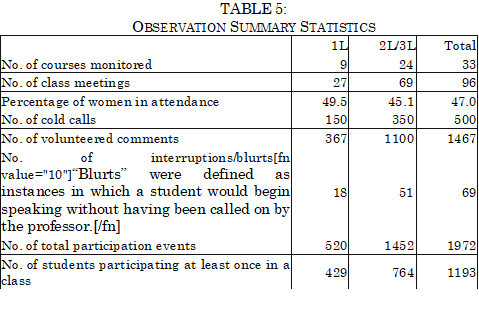

This study included four primary methodological components: classroom observations, professor interviews, a student survey, and analysis of achievement data. First, WAP observed ninety-six Law School class sessions during the Autumn Quarter of 2017. WAP trained student observers to observe, in pairs, their own classes three times each during the Autumn Quarter. The project observed twenty-four upper-level courses and all nine sections of doctrinal 1L courses (1L Legal Research & Writing classes were not observed). Students identified and recorded cold calls, as well as various types of voluntary participation events, professors’ responses to student participation, and the gender of the students participating. Observers also tracked whether students participated multiple times in a class session, allowing WAP to code the gender of students who participated three or more times in a session (“dominant participants”). To analyze the data from classroom observations, WAP averaged (using a simple mean) the number and type of participation events by gender observed by all the observers for a given class session. Statistical significance was calculated using paired samples t-tests. The tests compared the mean of the variable of interest (e.g., the percent of total observations made by women, averaged across classroom observations) with the mean of the class composition (the percent of women enrolled in that class).

Second, WAP interviewed fifty-three professors during the Autumn, Winter, and Spring Quarters of the 2017–2018 school year. WAP reached out to all full-time teaching faculty, Bigelow fellows, clinic directors, and some additional clinical faculty for interviews. WAP trained pairs of students to conduct thirty to sixty minute interviews using a standardized interview script that included questions about pedagogical strategies, mentoring relationships, and other areas of concern for women at the Law School. Professors were also asked to fill out data sheets including quantitative information about the numbers of letters of recommendation and references that they provided within the preceding calendar year as well as the numbers of research assistants they employed. WAP collected these data sheets from thirty-seven professors.

Interview data was analyzed using a qualitative coding software called NVivo. WAP created a list of fourteen thematic codes, and certain portions of the interview notes were assigned to different codes. In drafting the report, the authors counted the number of professors who expressed a given view by relying on the codes thematically closest to each view. Although the interviews varied to some extent in terms of length and content, they provide a useful window into professors’ perspectives on gender at the Law School, as well as student life more generally.

Third, WAP conducted a student survey in the Winter Quarter of 2018. The questions were modeled on the student surveys administered at Harvard and Yale, revised and tailored to UChicago. The questions were reviewed and tested multiple times by professors, law students, and a Ph.D. student in the Sociology department. Through a combination of open-ended and multiple-choice questions, the student survey examined students’ experiences and views with regard to their decisions to enroll at the Law School, their classroom learning, their participation in and satisfaction with student life and extracurricular activities at the Law School, their perceptions of their own successes and failures in terms of traditional markers of academic achievement, their relationships with faculty, and their career goals. Seventy one point eight percent of all J.D. students enrolled at the Law School at the time of the survey’s administration completed the survey, creating a unique snapshot of students’ interests and experiences at the Law School.

WAP conducted the survey on the Qualtrics platform. WAP then analyzed the data using the Reports function in Qualtrics to generate the percentages and absolute numbers of responses to most of the questions on the survey. Team members used Stata to both double check all the percentages and calculate statistical significance for any possible differences. In cases in which the response solicited in the survey was numerical, WAP tested for statistical significance in any differences between men and women respondents using a two-sided t-test. For the remaining cases in which the response type was categorical, WAP used a Pearson chi-squared test.

Finally, WAP compiled, counted, and analyzed publicly available data on students’ academic achievement and career outcomes, including participation in law journals, first-year writing prizes, honors at graduation, clerkships, and moot court participation. WAP worked with a team of statisticians from the University of Chicago’s Statistics Department’s Consulting Program to analyze the data collected and to perform statistical significance tests. Statistical significance was only calculated for the 2014–2017 period because WAP was only given access to the gender breakdowns at graduation for those classes.

In the following sections, we have used the terms “significant” or “significantly” to denote statistical significance. Where a level of statistical significance is not specified, we are referring to statistical significance at the .05 level.

III. Findings

This study produced broad initial findings on many aspects of women’s experiences at UChicago Law. Overall, women have yet to reach parity with men in many indicators of academic achievement and satisfaction with their experiences at the Law School. But there are also many areas in which women are doing well. The main findings are reproduced below.

A. Class Composition

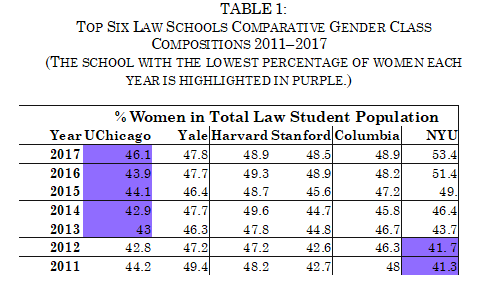

For each of the years 2011 through 2017, UChicago Law’s student population had a slightly larger gender disparity than any of the other top five law schools (as ranked by US News and World Report).8

For the first time in the history of the Law School, the Class of 2020 entered with an equal proportion of men and women. However, class composition data from the last four years demonstrates that classes tend to gain considerably more men than women between the 1L and 2L years as transfer students, leading to more heavily male class compositions in the remaining two years of law school.

B. Academic Achievement and Outcomes

WAP’s findings identify areas of significant progress, as well as serious roadblocks, for women students at UChicago. As discussed below, the p-values for achievement differences in this sub-section reflect the likelihood that the difference between the rate of achievement for each gender (on each metric discussed) and that gender’s representation in the average class is due to chance. The p-values for survey results measure the probability that the difference in the responses between the two genders is due to chance.

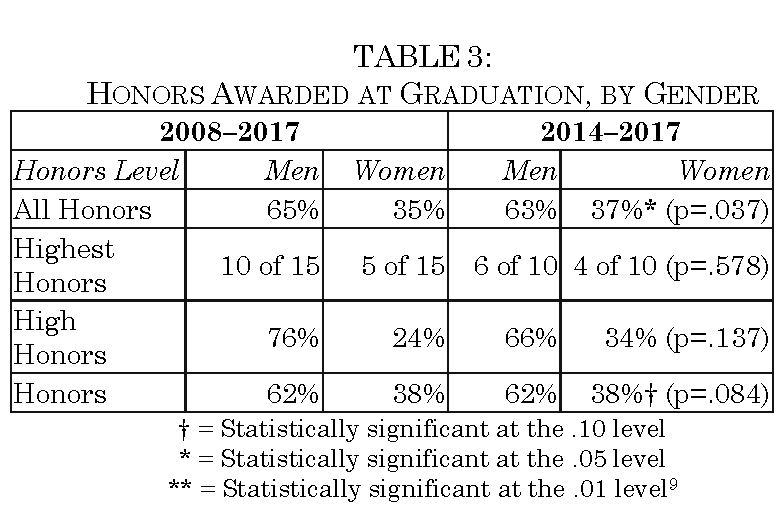

In terms of academic achievement, women are significantly less likely to receive academic honors at graduation than men. Women are also underrepresented at each specific level of honors, though those results are not significant except for Honors, which is marginally significant.

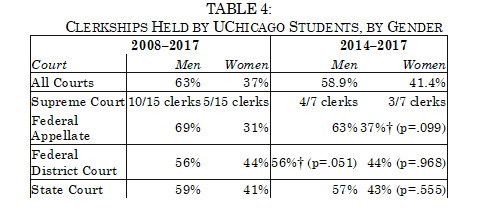

Women are also less likely to clerk in federal courts. Two differences are marginally statistically significant: men are less likely than would be expected based on their representation in the class to clerk for federal district courts, and women are less likely to clerk at federal appellate courts. The other rates of representation below show underrepresentation of women in clerkships, but not at statistically significant rates.

Additionally, women are significantly less likely to join the Law Review. From 2008 to 2017, Law Review staff was composed on average of 67% men and 33% women. These percentages were similar for the 2014 to 2017 period: the staff was composed of 65% men and 35% women. The difference between the percentage of the women in the Law School class from 2014 to 2017 and the percentage of women on the Law Review’s 2L class for those years is statistically significant (p=.016). The Legal Forum, another UChicago law journal, has historically had much greater gender parity. Its staffers over the last ten years have been 50% men and 50% women. Between 2014 and 2017, women’s presence surpassed that of men in the Legal Forum staff, with 53% of positions. The difference between the percentage of men in the class in those years and men’s representation on the Legal Forum staff is highly statistically significant (p=.007). Over the last ten years, the Chicago Journal of International Law (CJIL) staffers have been 54% men and 46% women.

Staffers from all three journals are selected through the annual writing competition. Overall, women complete the writing competition at a lower rate than men. Among 2L and 3L women, 50% reported participating in the writing competition, compared to 65.1% of men, a statistically significant difference (p=.013). These numbers likely fluctuate somewhat by year: within the 2L class, 43.3% of women reported participating (p=.038), while in the 3L class 56.5% of women reported participating (p=.130). 1Ls surveyed indicated that they planned to complete the writing competition at rates roughly balanced by gender. 69.1% of 1L women and 70.4% of 1L men surveyed reported that they planned to participate in the journal writing competition (p=.853), and 22.6% of women and 18.3% of men were not sure whether they planned to participate (p=.509). These differences are not statistically significant.

Additionally, survey results indicated that women were significantly less likely than men to report performing academically better than they thought they would at the Law School. 24.1% of women and 33.0% of men reported that result (p=.043). In contrast, 29.1% of women reported doing worse than they expected, as compared to 20.5% of men (p=.042).

C. Classroom Dynamics

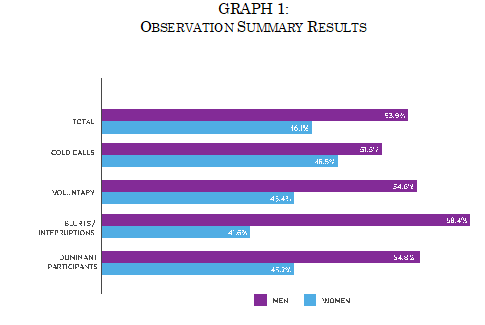

WAP’s classroom observation data indicated that men and women participate roughly equally in UChicago classrooms. Women, however, participate voluntarily in class significantly less often than men do. Women’s rates of voluntary participation may be affected by the gender of the first person to speak in a class, as well as the gender of the professor. Men are also much more likely than women to enjoy classroom participation. The p-values in this section represent the probability that the differences between the rate of participation for each gender and that gender’s representation in each class are due to chance.

1. Summary results

The raw numbers of classes, class sessions, and participation events observed by WAP volunteers are listed below.

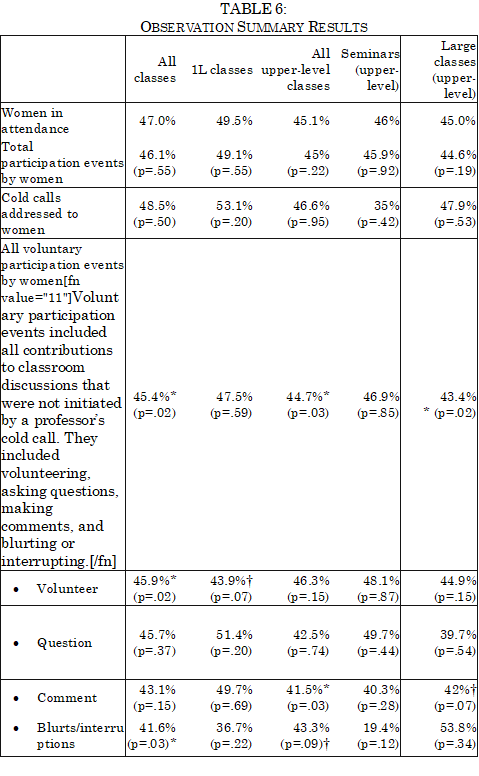

Overall, men and women participated roughly equally in the classes that WAP observed in the Autumn Quarter of 2017. Although women participated at a rate slightly lower than their rates of attendance, those differences were not statistically significant in any category of class (1L classes, 2L and 3L classes overall, 2L and 3L seminars, or upper-level large classes).

The percentages of each type of participation event by women in different categories of classes are listed below.

2. Voluntary participation

Men and women did participate voluntarily in class at different rates; men participated voluntarily more frequently than women did. These differences are statistically significant at the .05 level in all class sessions observed overall, in upper-level courses in general, and in large upper-level courses. The differences between men’s and women’s voluntary participation rates were not statistically significant in 1L classes or in 2L and 3L seminars.

TABLE 7

Table 8 breaks down participation rates by round of observation (“Round”). WAP conducted one Round in late October (near the beginning of the quarter), one in early November, and one in late November (near the end of the quarter). The gap in voluntary participation between women and men seems to have closed as the quarter progressed.

TABLE 8

a. Professors’ perspectives on student volunteering

Twenty-one professors noticed the small but significant difference in the frequency with which women and men participated voluntarily, but eleven reported that they did not notice a difference or that it did not occur in their classes. Three professors said that they were not sure about whether men and women participated with different frequency, and one observed that women speak more than men. At least five professors who believed that there was a gendered difference in student participation rates (or were not sure if there was) expressed the belief that the difference is small and does not generally affect the quality of contributions. One professor remarked, for example, that male and female students are “similarly talkative, similarly prepared, similarly strong and informed about what they say.” Still, nine professors observed that outlier students who consistently speak too much are more likely to be men.

Twelve professors also noted that men and women’s styles of participation differ. For example, one professor noted that male students who volunteer are “more often trying to profess a view,” while women are more likely to speak “to clarify a view.”

b. Students’ explanations for gender disparities in participation

Students surveyed offered various possible explanations for why men might volunteer in class more than women. By far, the most common explanation students offered was that they believe men are less likely to be self-conscious about the value of their contributions or sensitive to norms against excessive participation. Many students also commented that male and female students’ styles of participation differ. For example, one student noted that when men speak “they speak more confidently than women.” Another student stated that women “are much more likely to use hedging language.”

3. Cold-Calling

Five hundred of the 1,972 (or 25.4%) participation events that WAP observed were cold calls.

Overall, professors cold called men and women roughly equally. 48.5% of cold calls observed were of women. This number is slightly higher than women’s attendance in the observed class sessions overall (47.0%), but the difference is small and not statistically significant (p=.500).

Classes in which there was more cold calling were not observed to have higher rates of female participation overall. In fact, the reverse was true. Women were observed to participate voluntarily slightly less in class sessions in which at least 50% of participation events were cold calls (women accounted for 39.5% of the voluntary participation events in these classes) than in class sessions in which fewer than 50% of participation events were cold calls (women accounted for 46% of voluntary participation events).12

TABLE 9

a. Professors’ perspectives on cold calling

Thirty-three professors reported that they cold call regularly, especially in large classes. Professors are largely positive and often enthusiastic about cold calling. Fourteen professors stated that they see cold calling as a good way to help students learn. One professor reported that “outside of clinics,” cold calling is “one of the best forms of preparation for practice we give our students.”

Twenty professors stated that they attempted to ensure that there was gender balance in who they called on, either within a single class session or across several class sessions.

Notwithstanding the generally favorable view professors had of cold calling, some professors noted that it may have drawbacks. One professor remarked that cold calling “sometimes creates a passivity in the classroom that lessens student engagement.” Four professors pointed out that cold calling may make some students uncomfortable in a way that is counter-productive.

4. First speaker gender

WAP’s findings identified differences in women’s rates of voluntary participation based on the gender of the first speaker in a class. Those results are provided below.13 Overall, in the forty-three observed class sessions in which the first speaker was a man, women were responsible for only 40% of total participation events and 39.4% of voluntary participation events. Both those differences were statistically significant. On the other hand, in the forty-seven class sessions in which the first speaker was a woman, women were slightly more likely to participate than would be expected based on the class gender composition, though those differences were not statistically significant.

TABLE 10

The strength of the relationship between a male first speaker and subsequent female participation also seemed to decrease as Autumn Quarter went on. Overall, the negative correlation of a male first speaker with female volunteering was not statistically significant after the first round of observations in late October.

TABLE 11

5. The effect of the professor’s gender

Students’ course loads tend to include classes taught by fewer female professors than male professors. Overall, 2Ls and 3Ls had a mean of 3.2 male professors and 1.5 female professors in Autumn Quarter 2017. The difference was even starker for 1Ls, who had a mean of 1.2 female professors and 3.8 male professors (including Bigelow fellows) in Autumn Quarter 2017.

In classroom observations, women participated slightly more—but not statistically significantly more—when in class with female professors. The percentage of total participation events by women in a class with a male professor (across all class years) was 45.3%; in classes with female professors it was 49.14%. Women were, however, significantly less likely to participate voluntarily in classes with male professors than their attendance in the classes would suggest. In those classes, only 44.9% of voluntary participation events were accounted for by women, a statistically significant difference (p=.03).

TABLE 12

6. Students’ perceptions of class participation

Overall, students expressed considerable satisfaction with their experiences in the classroom at UChicago Law. Forty six point six percent of survey respondents reported that their classroom experience at the Law School has been “somewhat positive,” and 38.2% reported that it has been “very positive.” These numbers are similar across class years.

Despite their general satisfaction with classroom experiences at the Law School, women and men experience class participation somewhat differently. While 42.5% of male students enjoy participating in class, only 27.3% of female students reported the same (p=.001). Similarly, 22.5% of male students dislike participating in class, and 43.2% of female students dislike it (p<.001).

Men are more likely to report that they themselves participate in class more often than their classmates. Although the gap in male and female answer rates on this question is smaller than the gaps described in the previous paragraph, it is still highly significant: 37.5% of men and 25.0% of women report that they participate either somewhat or far more often than their classmates (p=.006). Similarly, but less significantly, 39.0% of men and 44.1% of women report that they participate either somewhat or much less often than their classmates (p=.291).

D. Faculty Relationships and Mentoring

Women students report outcomes similar to or better than men in most mentorship metrics. Most students at the Law School report having at least one mentor among the faculty, and women reported having slightly more mentors on the faculty than men. Women are significantly more likely than men to serve as research assistants. Professors also write letters of recommendation for similar numbers of women and men, and women and men report having similar numbers of professors they would feel comfortable asking for letters from.

1. Mentorship generally

Five professors reported that they believe that students who actively seek mentors have a more rewarding law school experience than those who do not. Overall, when asked about their interactions with professors outside of class, students across all years responded that they were positive: 47.3% of respondents said they were “very positive,” and 40.2% of respondents said they were “somewhat positive.” The results did not vary significantly by students’ gender. 85.9% of women and 88.5% of men reported that their interactions were somewhat or very positive (p=.428).

In interviews, professors were divided in their opinions about what the appropriate or optimal role of a mentor should be. But despite these differences, there was widespread agreement among professors that gender does not make much difference to the mentoring relationship.

On average, most students at UChicago Law have at least one mentor on the faculty, and women have slightly more mentors than men. Women at UChicago Law reported having a mean of 1.8 mentors each, and men reported having a mean of 1.5 mentors. This difference is significant at the .10 level (p=.086).

Mentorship seems to increase over time. 3L women and men reported having more mentors on average than members of the 2L class, and 2L students reported having more mentors than 1Ls, suggesting that students gain mentors as they spend more time in law school. However there are differences based on gender within each class. More 1L men feel they do not have a mentor compared to 1L women, though this difference is not statistically significant: 54.9% of men reported not having a mentor compared to 44.0% of women (p=.179). Of the 1L survey respondents, the average number of mentors for women was 1.1 and the average number of mentors for men was 0.7 (p=.023).

2L and 3L men still reported having fewer mentors than 2L and 3L women: 27.1% of men feel like they do not have a mentor compared to 19.9% of women (p=.163). The average count of mentors for women and men:

TABLE 13

The Law School’s clinical opportunities are sources of mentorship relationships for many students. One clinical professor stated: “Mentorship is at the core of what we do as clinical faculty.” Sixteen students reported that they found mentors through their participation in a clinic. For example, one extolled the benefits of working with clinical professors who “take time to ask about aspects of our lives outside of pure academics and get to know us as people rather than as law students.”

2. Letters of recommendation and employer references

According to the data sheets that faculty members submitted, faculty wrote letters of recommendation for clerkships slightly more frequently for men than for women, but the difference was not statistically significant. A total of 44.1% of clerkship letters written in the last year were for women and 55.9% were for men (p=.956).

WAP also asked student survey respondents for the number of faculty members they felt comfortable asking for letters of recommendation. Students’ reports of the number of faculty members that they felt comfortable asking for letters of recommendation varied less by gender than they did with regard to mentorship (see above). On average, men and women across all classes have nearly equal numbers of professors they would feel comfortable asking for letters of recommendation.

TABLE 14

Twenty three point eight percent of 1L women and 22.5% of 1L men surveyed did not have a faculty member they felt comfortable asking for a letter of recommendation (p=.852). Of 2L women, only 4.5% did not feel comfortable asking for a letter from any professor compared to 6.0% of 2L men (p=.698). Of 3Ls, 10.1% of women compared to 1.6% of men did not have any professor from whom they would feel comfortable asking for letters of recommendation (p=.042).

3. Research assistantships

In the year covered by the professor data sheets WAP collected, 57.5% of research assistants employed by the professors who submitted such data were women and 42.5% were men, a difference that is statistically significant (p=.012). Six professors reported finding their research assistants either by posting the positions on Symplicity (an online job-search database used at the Law School) or by emailing their entire 1L class. Five professors stated that they hire research assistants in other ways, including hiring students who approach them proactively or recruiting students with the top grades in their classes.

4. Office hours

Professors vary in their approaches to office hours. Eleven reported having no scheduled office hours and instead inviting students to stop by at any time. One professor provides scheduled time slots for which students can sign up. Other professors schedule specific office hours but do not require students to sign up for time slots within that window. Professors largely were unsure what approach would be best.

Generally, professors reported that there is no difference in the frequencies with which women and men visit their office. But at least nine noticed differences in the topics men and women visited to discuss. Two professors reported that men were slightly more likely to want to discuss non-specific topics, unrelated to class, while women were more likely to visit with specific class-related questions. Finally, six professors noted that men are more likely to stop by their offices without an appointment.

Student survey responses roughly match what professors reported in their interviews: there is not much difference in the frequency with which women and men attend office hours. Of 2L and 3L survey respondents, men reported attending office hours more than women, but the difference was not statistically significant: 51.9% of men reported attending at least once per quarter, compared with 42.7% of women (p=.130). 1L women, on the other hand, attended office hours at a higher rate than 1L men, and this difference was marginally significant: 87% of 1L women reported attending at least once per quarter, compared to 76% of 1L men (p=.080).

E. Faculty Diversity

Although WAP set out to research primarily the student experience at UChicago Law, issues of representation on the faculty, as well as the experiences of current faculty members who are women or minorities, came up with an inescapable frequency in both professor interviews and student survey responses. In the spring of 2018, the Law School had thirty-seven members of the full-time research faculty, of which only ten were women. The clinical faculty was more diverse—of the twenty-one total clinical faculty members, twelve were women. But 1Ls often do not have any interaction with the clinical faculty, and because clinics are optional, many students graduate from the Law School without having any significant interaction with a clinical faculty member.

Students are acutely aware of this gender imbalance and expressed their dissatisfaction with it again and again, some identifying it as a significant failure of the Law School. Generally, students reported that having a diverse faculty is important and that the Law School “would benefit greatly from having more female faculty members.” Professors are also concerned with the negative impact of the lack of diversity. One professor suggested that a more diverse faculty would be attractive to students. Some professors believe that mentorship responsibilities are not distributed evenly between female and male faculty, and that the female faculty bear the responsibilities of acting as mentors more often than men, if only because there are fewer women than men to share the burden. Both the faculty and the administration expressed concerns about the burden it places on female faculty to teach 1L classes.

Some women faculty members shared examples of the challenges they had faced at the Law School during their interviews. Those accounts are explored more fully in the full-length report. Additionally, the full-length report describes some of the difficulties the Law School administration reports facing in hiring a diverse faculty.

F. Student Experience and Activities

Women’s experiences at UChicago differ from men’s in areas beyond the classroom or their faculty relationships. This section explores trends in student satisfaction overall, students’ decisions to enroll at UChicago, students’ reports of interactions with their classmates, their career preferences and goals, and their participation in organized extracurricular activities. The p-values in this section denote the probability that the difference in response between men and women students on a particular question was due to chance.

1. Perceptions of the law school and matriculation decisions

Survey respondents were asked, “Did you have any reservations about attending the University of Chicago Law School?” They were asked to check all responses that applied out of a set of seven options, which included “neighborhood safety,” “law and economics focus,” “lack of fun,” “conservative political reputation,” “lack of diversity,” “I had no reservations,” and “other.” If a survey respondent selected the “other” option, he or she was given the chance to write in any additional reservations that were not included in the initial set. Fifty-seven survey respondents wrote in additional concerns not listed in the initial set of seven fixed choices. Overall, women were significantly more likely to express the reservations described below, and were significantly less likely than men to report having no reservations about enrolling at UChicago. Seventeen point three percent of women and 26.5% of men reported having no reservations about their decision to enroll at UChicago (p=.022). The following responses from students reflect the concerns they remember having when they considered whether to attend UChicago Law (they do not necessarily reflect students’ judgments about whether such concerns were well-founded in reality).16

GRAPH 2

Briefly, the largest differences between men and women students’ responses were in the following categories:

- Lack of Diversity: Lack of diversity was the most commonly reported reservation for women, with 48.6% of female survey respondents reporting it. In contrast, 27.0% of men were concerned by a perceived lack of diversity (p<.001).

- Law and Economics: Male students were significantly less likely (p<.001) to see the Law and Economics focus of the Law School as a cause for concern when deciding whether to matriculate: 36.4% of female survey respondents reported this concern, versus 16.5% of male survey respondents.

- Political reputation: 48.2% of female survey respondents reported that UChicago’s conservative political reputation gave them pause when enrolling. In contrast, only 31.5% of men checked this box. Although this was the most commonly reported reservation for men (and the second most commonly reported reservation for women), the difference between men and women’s responses was still highly significant (p<.001).

- Ten students made use of the “other” response option to report that the Law School’s liberal political reputation or lack of conservative faculty had been a cause for concern for them in their decision to matriculate.

- Safety: 27.3% of female respondents and 22.5% of male respondents reported being concerned about neighborhood safety when deciding whether or not to attend UChicago. The difference was not statistically significant (p=.0259).

- Competition, rigor, and intensity: Women disproportionately made use of the “other” option to write in that they had reservations about UChicago’s reputation for competitiveness, although the concern was also voiced by a male student. Three women noted concerns about “academic rigor,” “intensity of the quarter system and curriculum,” and “stress culture.” One professor explained such a concern, noting: “There is an institutional commitment to free exchange of ideas and having hard conversations, but that can give [prospective students] the idea that you have to be really tough to go here.”

2. Professional goals and career planning

WAP survey respondents were asked what kind of legal work they hope to do within their first ten years after graduating from the Law School. Male and female respondents reported significantly different rates of interest in every career area questioned except government work. Women were significantly more likely than men to report an interest in doing public interest work. Men were significantly more likely to be interested in private legal practice, legal academia, clerking, and non-legal work.

Table 15

Women are less likely than men to participate in On-Campus Interviewing (“OCI”). Seventy-four point three percent of 2L and 3L women and 83.7% of 2L and 3L men reported participating in OCI (p=.059).

Women and men who participated in OCI reported getting jobs through the process at roughly similar rates. Eighty-three point nine percent of 2L men and 90.4% of 3L men who participated in OCI reported getting jobs through the process. Eighty-one point six percent of 2L women and 92.3% of 3L women who participated in OCI reported getting jobs through the process.

Significantly higher percentages of women than men reported an interest in doing public interest work at some point during the first ten years of their legal careers (see the table above). Perhaps correspondingly, women were more likely to forgo OCI in order to pursue public interest work during the 2L summer—16.2% of 2L and 3L women reported making that choice, compared to 11.6% of 2L and 3L men—though the difference is not statistically significant (p=.286).

Female students also are historically more likely to participate in more pro bono work during their time at the Law School, earning the Dean’s Certificate of Recognition for completing fifty hours of pro bono service at disproportionately high rates. Fifty-nine point six percent of Certificates given out since the award’s inauguration in 2013 have gone to women.

TABLE 16

3. Student satisfaction and culture

The vast majority of students reported feeling positive about their decision to enroll at UChicago Law. However, men and women did so at significantly different rates. Eighty-four percent of male respondents and 75.5% of women either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, “[g]iven my experience so far, I would choose to enroll at the University of Chicago Law School again” (p=.030). Male students were more likely than female students to report strong agreement with the statement (p=.030). Women were more likely to report neither agreeing nor disagreeing with the statement (p=.045), and more likely to report strong negative feelings about their decision to enroll (p=.085).

Graph 3

4. Improved satisfaction after 1L

Major gender disparities were not evident in survey respondents’ assessment of whether their law school experiences had improved since the end of 1L. The majority of students overall felt that their experiences at the Law School had improved at least somewhat since finishing 1L year. Sixty-two point seven percent of 2L and 3L students either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “my law school experience has improved since 1L.” The less positive view of 1L year compared to later years of law school is significant because, as one professor put it: “A huge component of the Law School culture goes into how we do 1L curriculum. How 1L classes are run makes a big difference, and culture is set very early.”

5. Interactions between students

Male students report having positive interactions with their fellow students at higher rates than female students and are also more likely than women to characterize these interactions as “very positive” rather than “somewhat positive.”

Graph 4

Despite the fact that the vast majority of students expressed positive impressions of their interactions with other students, in response to an open-ended question soliciting “other observations or suggestions . . . about gender dynamics at the Law School,” nine female respondents expressed negative feelings about the way that they were treated by fellow students in the Law School community based on their gender. One such woman remarked: “As a woman, I think the most marginalized I have ever felt is at the Law School.”

6. Confidence

Many students and professors identified a confidence gap as a possible source of some of the gender-based disparities they saw at the Law School. Three female survey respondents reported concerns about their abilities to keep up or “compete with [ ] peers at U of C” as a reason why they had reservations about deciding to enroll at UChicago Law. One of these students characterized this concern as the work of “imposter syndrome.”

When asked about the most significant gender difference at the Law School, one professor remarked: “In a word, confidence. There are some students who are very accomplished, but are still not confident. Male students tend to seem more confident than female students.” Another professor echoed these sentiments: “In our society, women are raised to settle for something less than they are capable of achieving; that’s a problem that the Law School didn’t cause, but that the Law School can do something to correct.”

Of course, the Law School experience itself can also have an impact on confidence. A student posited one possible explanation: “[A] diversity of experiences and perspectives [among professors] would do a lot to make students feel like they actually deserve to be at the school. It’s hard to feel like . . . you’ve earned your seat in the classroom when most of your professors look the same (i.e., not like you).”

7. Extracurricular activities

a. Moot court

Over the past five years, 71% of moot court semi-finalists, 60% of finalists, and 67% of moot court winners have been men. Unfortunately, WAP was not able to obtain information regarding the gender composition of participants in the first round of competition for those years. Four survey respondents wrote about frustration with the way that the Moot Court competition is run and women’s consistent failure to advance to later rounds in meaningful numbers.

b. Law student organizations

1L men were members of fewer student organizations than 1L women on average, to a statistically significant degree. 1L men belonged to an average of 2.3 student organizations while 1L women were members of an average of 2.8 (p=.006). Two point three percent of 1L men who completed the survey were members of more than four student organizations while 9.5% of 1L female survey participants were members of more than four student organizations (p=0.090).

IV. Discussion

A. Class Composition

One of the most striking gender disparities the WAP study identified is the demographic makeup of the student population. Class composition helps determine the kinds of voices that will be heard in classroom conversations and in the student body at large. Because WAP does not have access to admissions data, we are unable to answer many questions surrounding the historical imbalance in male and female enrollment at the Law School. The study does shed light, however, on some of the possible causes of the gender imbalance in the student population.

1. Attracting female students

Survey results suggest that women tend to have more reservations about deciding to enroll at UChicago Law than men do. If women are not enrolling because of the Law School’s perceived conservative political reputation, regardless of whether the reputation is accurate, then the Law School could be missing out on qualified female students.

The Law School’s perceived focus on Law and Economics might be having a similar effect on women’s enrollment. Female survey respondents were much more likely than men to choose the Law and Economics focus as a cause for concern when considering enrollment, and male UChicago students are significantly more likely to have majored in Economics as undergraduates than female students.17

Our study suggests that another reason for the gender imbalance in the student population is the significant gender disparity in who transfers into UChicago Law between the 1L and 2L years, as transfer classes appear to be heavily male. The pronounced transfer phenomenon is surprising and warrants further exploration. It is a major accomplishment for the Law School to have matriculated its first gender balanced 1L class, the Class of 2020. However, efforts to achieve equal representation will be incomplete if transfer classes introduce gender imbalances for the remainder of students’ law school careers.

B. Achievement Gaps

1. Journals

As is clear from the Academic Achievement and Outcomes section above, there is a significant gender disparity in who attains membership or a board position on the Law Review.18 This is the case notwithstanding the fact that women and men are approximately equally likely to serve on CJIL, and women are significantly more likely than men to serve on Legal Forum. All three journals use the same writing competition, traditionally held immediately after the 1L year, to select their staffers.

The most obvious reason why Law Review may have the highest ratio of men to women among the journals is that there may be a gender disparity in grades, since traditionally, two-thirds of staffer positions (approximately twenty-seven of forty) on the Law Review were filled by “grading on” (a process in which the journal accepts the people with the highest grades who completed the writing competition provided their writing competition submissions fulfilled a minimum standard). The Law Review’s selection processes changed in 2018, but the impact of those changes has not yet been studied. The remaining one-third of the positions have traditionally been based solely on an evaluation of the candidates’ writing competition submissions. CJIL and Legal Forum, in contrast, do not take grades into account when selecting staff members. Although WAP did not have access to 1L grades, the marginally significant difference in all honors awarded to women versus men from 2014 to 2017 suggests that women may on average receive slightly lower grades than men across their law school careers.

There also appears to be a gender skew in who completes the writing competition in the first place. Significantly more 2L and 3L male survey respondents reported completing the competition than female survey respondents did. Different rates of writing competition completion do not explain, however, the different degrees of gender disparity among the three journals, so different rates of completion of the writing competition cannot explain the Law Review’s gender skew entirely.

When it comes to serving on the journals’ boards as 3Ls, men and women’s behavior is substantially similar, suggesting that any difference in women’s representation on the journals’ boards is likely due to their different representation in the staffer classes in the first place.

2. Clerkships

Women’s rates of earning clerkships have improved somewhat over the past ten years. Overall, however, men are still more likely than women to clerk at the appellate level, and women are slightly more likely than would be expected to clerk at the district court level.19

The disparity in the ratios of men and women who attained federal appellate clerkships between 2014 and 2017 may be in part the product of a gender skew in grades.

The disparity may also reflect differences in the rates at which male and female students apply for clerkships. Women were significantly less likely to report an interest in clerking in the student survey. Women may also be particularly sensitive to discouragement given their historical underrepresentation in the legal field, at the Law School, on the faculty, and as clerkship and honors recipients and Law Review members, as well as their high comparative levels of concern about the Law School coming in. Any comparative lack of confidence on the part of women might make them even less likely to apply than they would be otherwise.20

The gender disparity in Law Review membership may also be a factor. In explaining the gender disparities among UChicago students who are hired as clerks, one professor noted, “the clerkship problem could be partially a Law Review problem in that judges want students who have had a certain type of writing experience, and they are familiar with the experience the journals provide.”

3. Grading and the achievement gaps

Many of the classic markers of academic achievement at the Law School, including Law Review membership, clerkships, other prestigious jobs, and academic honors, are determined, in whole or in part, by the same thing: grades. It is impossible for WAP to know definitively whether 1L grades vary based on gender because of the administration’s denial of WAP’s data requests. However, the significant gender-based disparity in honors awarded at graduation (described above) suggests that women tend to receive lower grades than men at least to some degree.21

All required 1L courses are blind graded, as are upper-level exam classes. Upper-level seminar grades are frequently based on reaction papers and research papers, which are not blind graded. Although blind grading may help avoid the effects of certain kinds of gender or other biases, it is not possible to know how that works in practice. There are several hypotheses that might explain the gender disparities in academic achievement:

a. Are female students not as strong academically upon arrival at the Law School?

One possibility is that women who enroll are less academically qualified than their male classmates.22 WAP’s lack of access to admissions data meant that we had no way to interrogate this hypothesis. If it is the case that female matriculants at the Law School are not as strong academically, it is unclear why the Law School is not able to attract better-qualified female candidates. It is possible, however, that the Law School is less attractive to women than it is to equally well-qualified men for the various reasons discussed earlier.

b. Does the law school environment disproportionately negatively impact female students’ morale or well-being in a way that results in poorer academic performance?

It could be that male and female students come to the Law School equally qualified and prepared to succeed, but that the Law School environment takes a heavier toll on women that detracts from their ability to achieve. This hypothesis is supported by the findings that women generally report positive feelings about interactions with their fellow students and classroom experiences and their decisions to enroll at the Law School at lower rates than men.

c. Do women have a distinctive writing style that professors disfavor, either consciously or subconsciously?

It is also possible that men and women write differently from one another, and that a stereotypically masculine writing style is favored by law professors grading exams. Some professors suggested that if this were the problem, one solution might be to vary the types of evaluations used in the academic setting. One professor stated: “If women are performing worse in exams . . . if we don’t as a school feel that that is representative [of] their mastery of their material, the biggest thing we could do would be to change how we evaluate people, rather than just saying men are better at law. I don’t accept that premise.”

It is likely that several of these phenomena are working together to cause or exacerbate gender-based achievement disparities. No matter the precise mechanism that produces achievement disparities, their existence is disturbing.

C. Classroom Dynamics

Overall, as described above, women and men participate in class at almost even rates (and rates that were more equal than those reported at Yale in 2012).23 However, men participate voluntarily significantly more frequently than women do.

1. Cold calling as an equalizer

Cold calling largely drives the almost equal rates of overall participation between men and women, considering the fact that men were significantly more likely to participate voluntarily than women were. Given that UChicago Law professors tend to rely heavily on cold calling in their teaching, it may not be surprising that participation overall is more gender-balanced at UChicago than at other schools (which some professors reported use cold calling less frequently). This indicates that most professors are likely doing a good job of cold calling men and women equally, and suggests that some form of cold calling is a good idea for many or most classes.

2. Explaining the voluntary participation gap

It is impossible to know all of the root causes behind men’s higher rates of voluntary participation in their classes. For example, men were more likely than women to report enjoying participating in class. It is difficult to know whether that is a cause of the voluntary participation gap, or an effect of it, but either or both are possible. Students posited some additional explanations, and there may also be valuable lessons to learn from the types of classes where gender disparities appear to be less pronounced.

First, voluntary participation rates of female students were higher in 1L classes than in upper-level classes. There are several reasons why that might be the case. For example, the Class of 2020, the 1L class at the time of the project, was the first class at the Law School to be 50% women. Women in that class might have felt more comfortable speaking up as a result of the better-balanced gender dynamics. Or, given women’s comparatively lower satisfaction with classroom dynamics, it could be that women are discouraged over time. Multiple effects might work together to help 1L women feel more comfortable speaking up in class, both voluntarily and when answering cold calls.

Second, voluntary participation in seminars is roughly equal across genders. Again, there are a few reasons why this might be the case, including that seminars are less formal and potentially less intimidating, and the possibility that men are more likely to have the confidence necessary to speak in large groups. Of course, women could also be more interested in the topics taught in smaller, upper-level seminars.24

D. Female Faculty

WAP’s data make clear that students value having female professors teach the 1L curriculum and that many believe that having a diversity of professors is important to their learning experience. The lack of female faculty is likely a factor behind the differences in male and female students’ experience at the Law School.

The lack of diversity among the faculty also results in female professors shouldering a larger burden in terms of teaching and mentorship.25 Because of the importance the administration places on having a diverse set of faculty teach 1Ls, women professors may simply have to do more (a result the administration acknowledges and states it is trying to avoid).

The importance the Law School places on teaching evaluations may also make it difficult to permanently hire qualified female professors. If gender biases impact student evaluations,26 equally effective female visiting professors might unfairly receive lower ratings than men.

1. Mentorship

The data collected suggests that women develop slightly more mentoring relationships than men (this result is significant at the .10 level). This may be a consequence of high rates of female participation in clinics. It is also possible that the fact that women are more likely to serve as research assistants accounts for their higher number of mentors, on average, since many professors and students reported developing a mentoring relationship that way.

It is unclear why women would have slightly higher rates of faculty mentorship than men and work as research assistants at significantly higher rates without correspondingly higher rates of comfort asking for letters of recommendation, higher rates of receiving letters of recommendation, or in turn, receiving as many clerkships as men.

E. Student Life and Satisfaction

1. Women’s satisfaction overall

While men and women both report high levels of satisfaction with various aspects of their life at the Law School, it is important to note that women consistently report satisfaction at rates lower than men do.

GRAPH 5:

Women’s and Men’s Experience Overall

There are many possible reasons for this lack of satisfaction. Women reported negative gendered interactions with their fellow students, the constant nagging of imposter syndrome, and the frustration of being taught by professors with whom they do not identify. Additionally, if women are less likely than men across the board to earn the classic markers of law school academic success—good grades, Law Review membership, appellate clerkships, graduation honors, and moot court prizes—it may not be surprising that they feel less satisfied with their experiences than men.

V. Conclusion and Recommendations

Overall, WAP’s findings show significant disparities between men’s and women’s experiences at the Law School along various axes, despite the real strides that women—and the Law School—have made over the

past ten years. In conclusion, WAP offers recommendations for future research, as well as for improving student experiences at the Law School.

WAP’s recommendations are targeted to three different audiences: the administration, faculty, and students. WAP recommends that the administration improve its collection, maintenance, and analysis of data. The administration should organize and analyze pre-existing data such as historical grade data and also gather new data by administering targeted follow-up surveys to the student body. WAP hopes that the administration will experiment with different class organization and assessment techniques in order to determine if certain class sizes or assessment types augment or decrease gender disparities in grades. WAP believes that the Law School should continue to seek to admit gender-balanced classes and should strive for more gender-balanced transfer classes.

WAP recommends that students think about the ways that gender impacts their classroom participation. All students should ask themselves whether their participation is motivated by a genuine question, desire to have the professor clarify something, or ability to make a previously unstated contribution to the discussion. If it is, they should participate enthusiastically. If a student is merely repeating a point someone else has already made or bringing up a subject that is only tangentially related to the material, the student might consider raising it one-on-one with the professor after class or during office hours.

Students—especially women—should also consider speaking more in class and continue actively seeking mentoring relationships. Both professors and students repeatedly asserted that one possible cause of the gender achievement disparities is a lack of confidence on the part of female students at the Law School. Though this common observation is apt, WAP warns that differences in confidence levels are not necessarily innate or predetermined: the findings of the study as a whole suggest that any gendered confidence gap should be understood to be at least in part a symptom of other gender-based disparities and dynamics occurring at the Law School.

Professors should set fixed office hours and publicize them. They should also make clear to students that office hours are not only for discussing class material, but that they are also happy to discuss students’ careers and other interests. WAP recommends that all faculty members affirmatively encourage students who make valuable contributions in class, do exceptionally well on exams, or show promise as future academics. In class, professors should make sure they often call on women first in a given class session, and consider cold-calling more if they can do it in a way that is gender-balanced.

WAP’s findings illustrate that while women have made strides at UChicago Law School, they continue to experience law school differently from men in some important ways. The authors hope that this report will continue to inspire conversations between faculty, administrators, and students about new paths forward for women at the Law School.

- 1WAP was unaffiliated with the Law School administration. Although WAP benefitted from the informal advice and guidance of members of the Law School faculty and administration, it was an independent project that defined its own goals, methods, and scope at each step in the process. WAP obtained approval from the University of Chicago’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) for each component of the study. WAP received funding from the Office of the Dean of Students, a University of Chicago Diversity and Inclusion Grant, and various law firms. None of the funds were conditioned on the content of WAP’s report in any way.

- 2Likely the most influential initial contribution was Lani Gunier’s 1997 book, which argued that traditional legal education, including the Socratic Method, was alienating for women. See generally Lani Gunier, Becoming Gentlemen (Beacon Press 1997); Claire G. Schwab, A Shifting Gender Divide: The Impact of Gender on Education at Columbia Law School in the New Millennium, 36 Colum. J. L. & Soc. Probs. 299 (2003); Allison L. Bowers, Women at the University of Texas School of Law: A Call for Action, 9 Tex. J. Women & L. 117 (2000). There is also considerable research on women’s underrepresentation in the legal profession more broadly. See generally Commission on Women in the Profession, A Current Glance at Women in the Law, American Bar Association, 2–7 (2017), https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/marketing/women/current_glance_statistics_january2017.authcheckdam.pdf [https://perma.cc/ZZ2N-9W2N]. Recent research has even identified disparities in the frequency with which male and female Supreme Court justices are interrupted by each other and by litigants. See generally Tonja Jacobi & Dylan Schweers, Justice, Interrupted: The Effect of Gender, Ideology, and Seniority at Supreme Court Oral Arguments, 103 Va. L. Rev. 1379 (2017).

- 3See generally Study on Women’s Experiences at Harvard Law School, Working Group on Student Experiences, 3–86 (Feb. 2004), https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/women/study-on-women-s-experiences-at-harvard-law-school.pdf [https://perma.cc/ZXH7-462K]. The results of the study were also published at Adam Neufeld, Costs of an Outdated Pedagogy? Study on Gender at Harvard Law School, 13 Am. U. J. Gender Soc. Pol’y & L. 511 (2005). In 2013, the Harvard Crimson published a three-part series on women at Harvard Law School. See Part I (with links to the following parts) at Dev A. Patel, Once Home to Kagan and Warren, HLS Faculty Still Only 20 Percent Female, Harvard Crimson (May 6, 2013), https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2013/5/6/hls-gender-part-one/ [https://perma.cc/HF25-M8ND]. The Harvard Law’s Women’s Law Association recently released updated numbers regarding achievement disparities between women and men at Harvard Law School. Molly Coleman, Harvard Law School’s Glass Ceiling, Harvard Law Record (Apr. 24, 2018), http://hlrecord.org/2018/04/harvard-law-schools-glass-ceilings/ [https://perma.cc/ D825-WDC7].

- 4Yale Law Women, Yale Law Students and Faculty Speak up about Gender: Ten Year Later, Yale Law School, 3–93 (Apr. 2012), http://yalelawwomen.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/YLW-Speak-Up-Study.pdf [https://perma.cc/LX6Y-AJBJ].

- 5Note that, from the very beginning of the study, some students made clear to WAP that they did not believe there were any gender disparities at the Law School. The data WAP gathered suggests that this is not the majority of the student body’s view, however, or the professors’. Additionally, classroom observations and achievement data point to basic differences in the way that women and men experience the Law School. When discussing the results from qualitative data gathering techniques such as professor interviews and responses to the open-ended questions on the student survey, WAP took care to focus on views that came up repeatedly, and to indicate the frequency with which certain comments were made, so as not to over-represent any one opinion as a consensus view if unwarranted.

- 6See Appendix K of the full-length report.

- 7See Appendix L of the full-length report. For more information on how WAP calculated baseline class composition for those years (an important step in many of the statistical significance calculations described below), see Methodology, Achievement Data of the full-length report.

- 8Best Law Schools, U.S. News & World Report, https://www.usnews.com/best-graduate-schools/top-law-schools/law-rankings [https://perma.cc/Q794-YYL8] (last visited Jan. 21, 2019).

- 9These symbols are used throughout to denote levels of statistical significance.

- 12Note that the amount of cold calling in a class may be correlated with class size (professors may be likely to cold call more in large classes), which may explain part of this result (given that women participate voluntarily less in upper-level large classes than they do in seminars).

- 13Note that whether men speak more in a class is likely a confounding variable with whether the first speaker in that class is a man, given that in a class where men speak more frequently a man is also more likely to be the first speaker. WAP was not able to complete additional testing to tease apart the relationship between these two variables.

- 16Unfortunately, WAP’s student survey did not include a question about why students chose to enroll. This information would likely also be interesting.

- 17This characteristic of the Law School’s student body reflects the broader trend of more men than women majoring in Economics as undergraduate students. See generally Elizabeth P. Jensen & Ann L. Owen, Pedagogy, Gender, and Interest in Economics, 32 J. Econ. Educ. 323 (2001).

- 18Lynne N. Kolodinsky, The Law Review Divide: A Study of Gender Diversity on the Top Twenty Law Reviews, Cornell Law Library Prize for Exemplary Student Papers, 24 (2014), https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1007&context=cllsrp [https://perm

a.cc/MDC5-36GW]. Kolodinsky’s article includes several hypotheses for why women are underrepresented on many flagship law journals. Another interesting source identified a gender disparity in law journals’ publication of student notes. Jennifer C. Mullins & Nancy Leong, The Persistent Disparity in Student Note Publication, 23 Yale J. L. & Feminism 385, 399 (2011).

- 19Disparities in the rates at which men and women receive clerkships at the United States Supreme Court extend beyond UChicago. For an interesting examination of the gender disparity in Supreme Court clerkships overall, see Cynthia L. Cooper, Women Supreme Court Clerks Striving for “Commonplace,” 17 Perspectives 1, 18 (2008). WAP was not able to compare UChicago’s clerkship gender disparities with those of other schools. The 2012 Yale report included statistics indicating that men were more likely than women to clerk at appellate courts. Yale Law Women, supra note 4, at 49. WAP was not able to directly compare the Yale numbers with the results for UChicago students because the years included in each sample were quite different.

- 20High achieving women often exhibit the imposter phenomenon or syndrome, lacking confidence despite their successes and doubting their abilities and the legitimacy of their accomplishments. See generally Anna Parkman, The Imposter Syndrome in Higher Education: Incidence and Impact, 16 J. Higher Educ. Theory & Prac. 51 (2016).

- 21For an exploration of gender-based grade disparities at Harvard Law School, see generally Coleman, supra note 3.

- 22The most recent report in the LSAT Technical Report Series, published by the Law School Admissions Council, found that men scored slightly higher than women on the LSAT. See Susan P. Dalessandro, Lisa C. Anthony & Lynda M. Reese, LSAT Performance with Regional, Gender, and Racial/Ethnic Breakdowns: 2007–2008 through 2013–2014 Testing Years, Law School Admi-

ssion Council (2014), https://www.lsac.org/data-research/research/lsat-performance-regional-

-gender-and-racialethnic-breakdowns-2007-2008 [https://perma.cc/B2P4-FTAH].

- 23Yale Law Women, supra note 4, at 3.

- 24See generally Daniel E. Ho & Mark G. Kelman, Does Class Size Affect the Gender Gap: A Natural Experiment in Law, 43 J. Legal Stud. 291 (2014). From 2001–2011, Stanford Law School randomly assigned first-year students to large and small sections of their courses. From 2008–2011 it also implemented changes in grading protocols. The changes resulted in even academic outcomes for women and men.

- 25Some research suggests that female professors are consistently asked for more support and favors from students than male professors are. See Amani El-Alayli, Ashley A. Hansen-Brown & Michelle Ceynar, Dancing Backwards in High Heels: Female Professors Experience More Work Demands and Special Favor Requests, Particularly from Academically Entitled Students, 79 Sex Roles 136, 137–38 (2018).

- 26See generally Kristina M. W. Mitchell & Jonathan Martin, Gender Bias in Student Evaluation, 51 PS: Pol. Sci. & Pol. 648 (2018) (suggesting female professors are rated by students on different criteria than male professors, often in a negative way).

- 27Note that the differences in positive interactions with faculty outside of class are not statistically significant.