#MeToo as Catalyst: A Glimpse into 21st Century Activism

I. Introduction

The Twitter hashtag #MeToo has provided an accessible medium for users to share their personal experiences and make public the prevalence of sexual harassment, assault, and violence against women.1 This online phenomenon, which has largely involved posting on Twitter and “retweeting” to share other’s posts has revealed crucial information about the scope and nature of sexual harassment and misconduct. More specifically, social media has served as a central forum for this unprecedented global conversation, where previously silenced voices have been amplified, supporters around the world have been united, and resistance has gained steam.2

This Essay discusses the #MeToo movement within the broader context of social media activism, explaining how this unique form of collective action is rapidly evolving.3 We offer empirical insights into the types of conversations taking place under the hashtag4 and the extent to which the movement is leading to broader social change. While it is unclear which changes are sustainable over time, it is clear that the hashtag #MeToo has converted an online phenomenon into tangible change, sparking legal, political, and social changes in the short run. This Essay provides data to illustrate some of these changes, which demonstrate how posting online can serve as an impetus, momentum, and legitimacy for broader movement activity and changes offline more characteristic of traditional movement strategies.

II. Why A Movement?

The problem is pervasive—in a recent nationwide survey, 81% of women report experiencing some form of sexual harassment in their lifetime.5 More than one in four have survived sexual assault.6 The simple hashtag #MeToo has added names, faces, and stories to the statistics in what is arguably the most powerful activism in the women’s movement in recent history. The sheer number of women experiencing harassment and assault make these issues ripe for social movements and collective action.7 This behavior goes beyond workplace misconduct, with statistics showing that harassment is ubiquitous and difficult to avoid. According to a large scale nationally representative survey, harassment is not something that only happens behind closed doors, with 66% of women reporting that they have experienced harassment in public places.8 Many are also vulnerable within their own households, with 35% of women experiencing sexual harassment at home. Workplace harassment is also a common issue, with 38 percent of women experiencing harassment in their workplace.

Harassment has become a part of our culture and everyday norms and takes many forms.9 Verbal sexual harassment is the most common form, experienced by 77% of women. An alarming 62% of women report being subjected to physically aggressive forms of sexual harassment, such as indecent exposure, being physically followed, and being groped or touched in a sexual way without consent. The internet, text messages and phone calls are also commonly used to harass, with 41% of women experiencing cyber sexual harassment. Twenty-seven percent of women have survived sexual assault, being forced into sex acts against their will.

Despite the pervasiveness of the problem, sexual harassment and assault commonly go unreported.10 In fact, sexual assault is the most underreported violent crime in America, with 70% of crimes never reported to police.11 Even after the rise of #MeToo, among survey respondents who said they had experienced workplace harassment in the past year, 76% did not officially report it.12 Many victims do not report because they fear retaliation, or think that reporting will lead to little or no consequences for the perpetrator.13 These concerns may be heightened when the perpetrator holds a position of power.14 In a sense, the common failure to report is confirmation that harassment is not only a part of the culture, but that the underlying gender inequality is still so accepted that reporting remains either ineffective or entails costs that are too high for victims. The Kavanaugh hearings were a paradigmatic example of both the inequality and the costs.15 Given the other changes we identify, the obstacles to reporting are a sobering reminder that some aspects of culture are stickier than others.

III. Origins of the #MeToo Hashtag

“Me Too” was first coined by Tarana Burke16 in 2006 to support women and girls, particularly women and girls of color, who had survived sexual violence.17 The term was popularized on October 15, 2017 when Alyssa Milano18 invited the Twitter world to use the hashtag to capture experiences of sexual misconduct by tweeting, “If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet . . . we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem.”19 Her tweet followed a New York Times report published 10 days prior, detailing Harvey Weinstein’s sexual assaults and harassment of numerous women; the hashtag #MeToo gained momentum shortly after.20 In issuing the tweet, Milano was acknowledging that despite the pervasiveness of harassment and assault, many victims have been silenced.21 In the next twenty-four hours, there were over 1 million tweets and retweets using the hashtag #MeToo.22

The hashtag #MeToo has served as a sign of empowerment for victims who may have feared they were alone, who thought they would not be believed, or who simply did not think justice was a possibility. Posting on social media has provided a simple and subtle way to speak out and share their experience. Within the first year, the hashtag #MeToo was used 19 million times on Twitter.23 Tweets in over 46 different languages have used the hashtag, and many new hashtags related to harassment and assault continue to emerge in these different languages.24 The magnitude of the social media response makes it clear that these are not just rare cases of bad behavior, but an all-too-common part of women’s experiences in the world. The response also provides a glimpse into the everyday attacks and shaming faced by victims of sexual abuse, and the persistent social acceptance of victim blaming, and its connection to larger, systemic forms of inequality.25

IV. Social Media Activism: A New Paradigm

The #MeToo phenomenon represents an example of a new type of collective action that has galvanized rights-based movements in the twenty-first century.26 Social media activism describes the effectiveness and viability of using social media platforms for political engagement in furtherance of social movements.27 Social media activism gained increased attention from scholars after the 2011 Arab Spring, where activists used Twitter to initiate conversations that helped fuel social and political change.28 For example, the hashtag #Egypt was instrumental in disseminating information during this revolutionary social movement.29 Online networks used the Twitter hashtag to help activists organize and share information, push for freer expression, and propel political change in neighboring countries.30

The current literature on social media activism primarily explores 1) how social media enables connectivity and organizing opportunities for existing political and social movements, and 2) whether social media has led to a new type of collective action, upending the need for organized groups supporting change, and enabling individuals to act.31 Classic theories on collective action and the public sphere have been contextualized to account for the new ways in which individuals can communicate via technology.32 For example, incorporating social media into resource mobilization theory, many scholars have argued that social media is an effective tool to recruit participants and organize campaigns, which are the social capital needed to promote the motives of any one movement.33 Social media helps connect individuals with similar grievances, linking them to groups and organizations that are working to combat parallel grievances.34

In other words, social media provides a crucial consolidating function by giving a common name to a set of concerns and thereby creating a one-issue community. If the community is big enough and the grievance sufficiently widespread, it also creates vital social visibility for injuries that were previously invisible. As Alyssa Milano rightly pointed out, it gives people “a sense of the magnitude of the problem.”35

Since the Arab Spring, a few other highly visible Twitter movements have been successful at propelling social, legal, and political change because they have tapped into injustices of sufficient magnitude.36 For example, #LoveWins began in September 2014 as part of a broad campaign of support for the LGBT community and its efforts to win the right to marry.37 The hashtag went viral on June 26, 2015 after the Supreme Court’s decision to legalize same sex marriage, with over 10 million tweets.38 To date, the largest social justice movement to be ignited on Twitter is #BlackLivesMatter.39 The hashtag first appeared in July 2013 after George Zimmerman was acquitted in the killing of an unarmed black teenager, Trayvon Martin.40 Since that time, the hashtag has been used in over 30 million Twitter posts.41 The hashtag continues to thrive in a steady stream of daily tweets, increasing in volume when relevant real world events occur.42 The hashtag has also helped to galvanize research and activism about racial bias, law enforcement reform, and the criminal justice system.43

V. Hashtags United: #MeToo and the Potential for Change

Following in the footsteps of #BlackLivesMatter, #MeToo has helped increase awareness and visibility of a pervasive societal problem, while amplifying the voices of those who have been injured. Optimists have argued that social media has been, essentially, a power equalizer that broadens access to political activism.44 Although Twitter is not a representative sample of the U.S. population, some have argued that social media activism has fewer divides along the lines of race, class, and gender than the activism of traditional social movements, due to the Internet’s accessibility.45 Moreover, social media networks, including Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and others, have become key parts of global and domestic civil society.46 On the one hand, it seems easier to “belong” on social media than it does in physical space. In a more practical sense, there are fewer barriers to participation, such as geographic restrictions, scarcity of leisure time, and cost. For example, people may be more willing and able to read 140 character tweets than travel to attend a live political speech. More individuals also get to take the stage, providing a sense of empowerment that everyone has a voice. Given this broader access, knowledge and information is no longer monopolized by political and economic elites and is communicated faster to the public. This allows for rapid mobilization of groups and gives greater opportunities to engage in public speech.47 Thus, social media represents a low-cost method through which people are able to organize, connect, and coordinate massive responses to injuries, events, and social change.48

However, some skeptics have argued that, rather than enable greater mobilization opportunities or connectivity among like-minded individuals, social media has created the “slacktivist.”49 Slacktivist is a pejorative term for an individual who participates in a social movement by liking or sharing social media posts promoting a particular cause.50 These individuals participate in a movement in ways that require minimal costs to participants; in a click or retweet, “the slacktivist can feel that he or she has helped to support the cause.”51 Critics of social media activism argue that, rather than playing a central role in social change, “slacktivists” do very little to produce social change and their participation is a poor substitute for in-person activism.52 In fact, they suggest that “slacktivists” may inhibit further engagement by giving “superficial” satisfaction to those sharing a post.53

Advocates for social media activism have argued that liking or sharing a post, even if a small contribution to a particular movement, represents the initial step toward greater engagement by those individuals.54 Moreover, this early participation acts to spread knowledge about a cause or issue that, if widespread, can motivate those with greater power and resources to seek cultural and institutional reform. #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter provide examples of how initial, rapid fire communication led to consolidation and mobilization, both by organized groups as well as individuals. While the initial contribution costs were minimal (involving shares or retweets), enough participation led to more tangible benefits for the movement, such as organized protests, funding for legal groups, and public awareness of discrete social problems. Eventually, this forced public officials to speak out and address those issues. It is also important to note that while there are no direct monetary costs to tweeting, there can be heavy emotional and reputational costs to participating. This is particularly true for working-class women, breadwinners, and immigrants, who may risk not only losing a job or being shunned, but also may risk deportation and separation from their community for speaking out.55

VI. An Empirical Analysis: Converting Conversations to Change

In Part A, we discuss our collection and analysis of over 13 million tweets to provide a brief overview of what people are talking about online under the #MeToo hashtag. In Part B, we examine the social, legal, and political changes occurring offline that have been inspired by the online activity.

A. The Conversations Happening Online56

First, it is ongoing social and political events that continue to keep the #MeToo hashtag relevant.57 An analysis of over 13 million tweets collected by the Massive Data Institute (MDI) at Georgetown University offers insights into the types of conversations taking place under the hashtag.58 Data reveal that the volume of tweets using the #MeToo hashtag is heavily correlated with social and political events, reaching a high point in September 2018 during the Brett Kavanaugh hearings.59 This is evidence of increased discussion and sustained momentum, demonstrating that the activism was not simply a fleeting trend from October 2017. The types of events and the volume of #MeToo activity surrounding those events are telling. First, the range of the events––from activism such as International Women’s Day and the Golden Globes, to announcements about perpetrators such as Moonves and Cosby, to achievements of women, such as Time Person of the Year––is a strong indication of the emergence of an online community sharing and commenting on a wide range of activities.

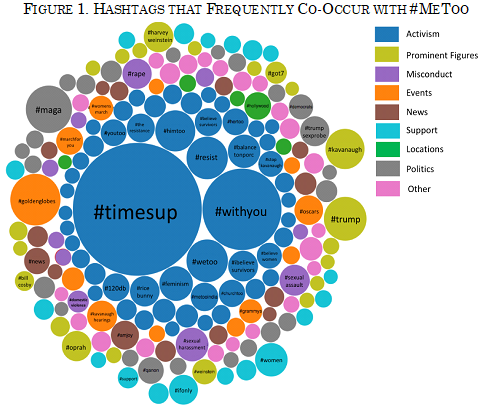

The MDI Research Collaborative also analyzed the content of the conversations. The first content analysis looks only at hashtags that co-occur frequently in the same tweet with #MeToo. Co-occurring hashtags are important because they highlight topics that online users are conversing about. The hashtag that co-occurs most frequently is #TimesUp, which pops up an impressive 310,000 times. #TimesUp, a next-step of #MeToo, was created by women in the entertainment industry on January 1, 2018 to raise money for a legal defense fund.60 Other hashtags that co-occur frequently with #MeToo include #withyou, #goldenglobes, #oscars, #rape, #sexualassault, #trump, #kavanaugh, and #resist. Figure 1 groups the most frequently co-occurring hashtags into topic areas. Each bubble in Figure 1 represents a frequent hashtag. The size of the bubble represents the relative frequency of the different co-occurring hashtags. Different colors of bubbles represent different topics. This figure highlights the variation in the types of topics that feature prominently in the conversation. Even with this variation, a large majority of hashtags are about activism (50 out of the top 180), including #TimesUp. This suggests an on-going interest in linking the Twitter conversation to action and social change. The co-occurrence of hashtags used in other countries for their #MeToo tweets–for example, #ricebunnies in China, #metooindia in India, #balancetonporc in France–is a reminder that both the underlying problem and recent discussion of sexual misconduct are global phenomena.

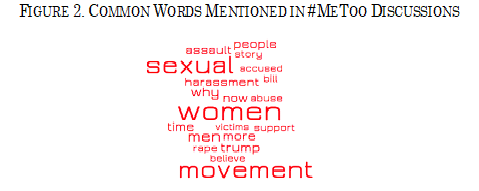

The next content analysis identifies words, excluding hashtags, which are most frequently used in the English tweets with #MeToo. The highest frequency words are shown in Figure 2. The larger words in Figure 2 occur in over 1 million tweets, while the small words occur in over 150,000 tweets. What is telling about these high-use words is the prevalence of misconduct words like harassment, sexual, and assault and activism words like movement and believe. These words represent further evidence of the personal nature of some of this online discussion and the openness with which people are sharing their stories, discussing them, and showing support for others.

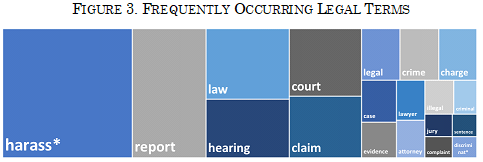

While the volume, hashtag topics, and frequently occurring words give us a macro-level view of the Twitter conversation, we are also interested in the more focused legal discussions taking place. As an initial step, we compiled a list of legal terms and determined how frequently they were used in #MeToo tweets. Figure 3 shows the legal terms that occur in at least 15,000 tweets. The most prevalent terms are those that have a root of “harass,” e.g. harassing, harassment, harassed, etc. Other legal terms include law, court, case, claim, report, and hearing. The use of such words suggests that legal action is a clear theme in the #MeToo discussion.

B. Social-political and Legal Change Offline Post #MeToo

Popularization of the #MeToo hashtag in October 2017 ignited social media and shook the power structures of media, television, and politics. Questions about the viability of #MeToo have loomed large, in part because of skepticism that the digital activism would translate into off-line action,61 as well as the limitations of the current legal landscape in providing relief for victims of sexual assault and harassment.62 However, as the movement continues to be culturally salient, we appear to be entering into a period of change, in the legal landscape as well as in society and politics more broadly. Dissatisfaction with the current status quo, and the strong desire for social and institutional changes in how we deal with sexual assault and harassment, is already leading to change.

1. Strikes and protests

The high volume of #MeToo tweets does not mean that traditional social movement tactics such as strikes, marches, and legal action are obsolete. The online activity not only serves as a catalyst for action, but also provides greater legitimacy and visibility to the action occurring offline, in some cases leading to rapid change. For example, in the private sector, activists have organized to address policies connected to sexual harassment and workplace safety, garnering media attention and public scrutiny for issues normally dealt with in closed-door conversations. In September 2018, for example, after 10 employees filed sexual harassment complaints with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), McDonald’s employees organized the first ever multi-state strike against the company’s existing sexual harassment policies.63 The workers carried signs that said “#MeToo McDonalds” and wore tape over their mouths that said “#MeToo.”64 Unite Here, a labor union that works primarily with the hospitality industry, worked in conjunction with union leaders in cities such as Chicago, Seattle, and Washington DC to organize massive campaigns advocating for hotels to provide panic buttons to hotel workers.65 Major hotel chains, including Marriott, Hilton, and Hyatt, subsequently introduced policies to provide panic buttons at all their properties by 2020.66 In October 2018, 20,000 Google employees walked out of corporate offices in 50 cities after demanding an overhaul of Google’s sexual harassment policies, particularly their policy of forced arbitration.67 In response, Google CEO Sundar Pichai announced changes to the policies, including optional arbitration. The decision followed in the footsteps of similar policy changes made by other tech giants, including Microsoft and Uber.68 Facebook followed suit soon thereafter.69

2. Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund

As discussed above, the hashtag #TimesUp is a solution-oriented branch of the #MeToo movement that seeks solutions to the problems #MeToo has helped identity. It refers to the Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund (TULDF), created to support lower income women and women of color who have been sexually assaulted or harassed in the workplace.70 TULDF was created by 300 actresses, female agents, writers, directors, producers, and entertainment executives seeking solutions for the systemic sexual harassment revealed by #MeToo.71 Consistent with resource mobilization theory, this is a clear example of how social media activism both outraged and inspired individuals, motivating them to organize, connect, and coordinate efforts to lead to tangible outcomes. The group’s mission, in part, is a response to early critiques that lower income women and women of color were being left out of the #MeToo conversation.72 This organization offline has helped provide the social and financial capital necessary to advance the cause. As of February 8, 2019, TULDF has fielded more than 4,000 requests for assistance from all 50 states and has raised $24 million.73 The funding is used to connect women experiencing workplace harassment and retaliation with attorneys, and in some cases, to media specialists. Legal defense funds like TULDF help victims to get justice. They also have the potential to enhance existing efforts to help working class women claim their rights in ways that generally carry steep financial burdens.

3. EEOC sexual harassment charges

The frequency of legal words emerging in #MeToo conversations online is consistent with recent reports that more individuals are reporting sexual harassment through legal channels since the start of the movement.74 According to the EEOC, the government agency responsible for enforcing workplace discrimination law, sexual harassment charges are up nationwide, the first increase observed this decade. The number of hits to the EEOC website for people searching for information on sexual harassment has also doubled.75 The agency has capitalized on #MeToo momentum by increasing lawsuits to enforce sexual harassment law and hold employers accountable.76 The EEOC has filed 50% more of these lawsuits than it did during the previous year, and has recovered $70 million for sexual harassment victims in FY 2018, compared to the $47 million it recovered during FY 2017.77 In terms of outcomes, the EEOC reported an increase in cause findings from 970 in FY 2017, to 1,199 in FY 2018. The agency also facilitated more successful conciliations, with nearly 500 in FY 2018, compared to 350 in 2017.78

4. State/Federal legislation

While this increased legal activity may be promising in showing that victims are seeking justice and accountability, long-term results will be limited if the movement does not lead to legal reform in order to enhance and broaden protection under sexual harassment law. Our current laws leave many individuals unprotected. For example, many workers are not protected by federal law, including: domestic workers, temporary workers, independent contractors, farm workers, interns, and those working for small employers.79 The statute of limitations to file sexual harassment claims under federal law is only 180 or 300 days, which is not enough time for many victims to process, reflect, and decide how to move forward.80 Non-disclosure agreements too often silence victims.81 And crucially, mandatory arbitration agreements increasingly prevent claimants from even accessing a court of law.82

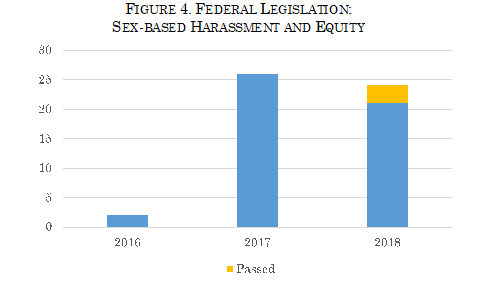

To examine the actual and potential policy changes following #MeToo, we reviewed all passed, proposed, and pending state and federal legislation that explicitly addresses sexual harassment and gender equity from October 2016 to December 2018.83 Legislators in several states have cited the #MeToo movement in discussing passed legislation and California has even coined some of the new laws the “#MeToo Bills.”84 In the U.S. Congress, from October 2016 to December 2018, 52 bills were introduced relating to sexual harassment, sexual assault, and gender equity in employment.85 This total includes a steep increase after the #MeToo movement took off in October 2017.86 While only two federal bills were introduced in 2016, 26 were introduced in 2017, 22 of which were following #MeToo, and 24 bills were introduced in 2018.87 Three of these bills have passed.88 See Figure 4. Of the three bills passed by Congress, one mandates anti-harassment training for Senators and Senate employees,89 another makes lawmakers financially liable for harassment settlements,90 and the third creates additional reporting requirements for sexual harassment in the military.91 Although a direct causal link cannot be drawn, this timeline suggests a strong correlation.

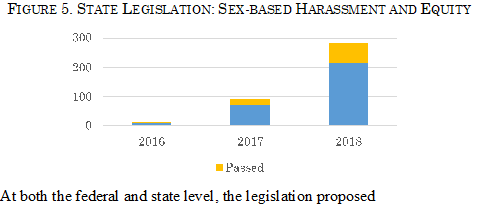

Even greater legal activity is occurring within the state legislatures. From October 2016 to December 2018, 384 bills were introduced across nearly all 50 states, plus the District of Columbia.92 The amount and timing of state legislation also suggests a very close tie with the #MeToo movement. While only 12 bills were introduced in 2016, 91 were proposed in 2017 (19 were introduced following #MeToo), and 281 were proposed in 2018.93 Ninety of these state bills have passed to strengthen the rights and protections of women in a number of states.94 Three were passed in 2016, 21 were passed in 2017, and 66 were passed in 2018.95 See Figure 5. The states with the highest number of bills introduced in 2018 include California (25), Illinois (17), New York (24), Pennsylvania (20), Tennessee (15), Virginia (12), Minnesota (14), and Connecticut (16). States with the highest number of Bills passed in 2018 include Illinois (8), California (7), Maryland (5) New Jersey (4), New York (3), Washington D.C. (4), Washington State (4), Virginia (3), and Tennessee (3).96

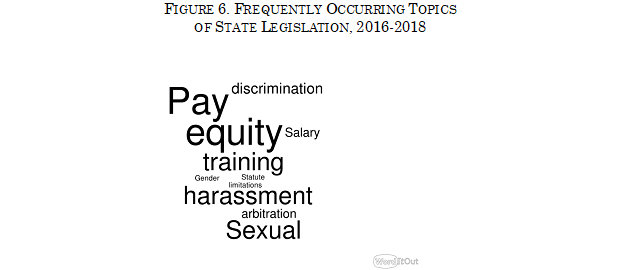

At both the federal and state level, the legislation proposed represented direct remedies to several institutional and cultural issues at the heart of the #MeToo movement. Almost all states and the federal government introduced legislation addressing pay equity and salary discrimination between male and female government employees.97 A majority of states introduced legislation mandating sexual harassment training programs for government employees or introduced legislation improving existing training.98 Several states also introduced legislation requiring government contractors or companies that receive federal funds to have harassment-training programs in place.99 Numerous states also introduced legislation to end mandatory arbitration in sexual harassment cases, or to extend the statute of limitations for filing sexual harassment claims.100 Figure 6 outlines these most frequently occurring topics in the state legislatures; pay equity was the most frequently introduced legislation, followed by sexual harassment training, with gender discrimination, statute of limitations, and arbitration also occurring frequently in several states.101

5. Tort claims

Some scholars also suggest that #MeToo will have an impact on tort law and will lead to more legal actions by victims of gender-related and sexualized injuries such as domestic violence, rape, sexual assault, sexual harassment, and reproductive injuries, particularly against third-party actors and when there are statutory gaps.102 Torts may sometimes be a better legal avenue than Title VII and Title IX because tort laws often have less strict deadlines for filing a claim. Additionally, plaintiffs who are not official employees of the defendant employer, or who are not students attending a defendant’s educational institution, currently have no civil rights claim under these statutes.103 In some cases, common law tort claims may provide the only avenue under which they could seek redress. Tort claims also provide recovery or the right to seek damages from the offending individual, whereas Title VII and IX claims can only be directed against the employer or the educational entity itself.104 The most commonly brought tort actions related to sexual harassment, sexual assault, and rape are intentional or negligent infliction of emotional distress, assault and battery, invasion of privacy, intrusion, as well as employment-related common law torts, such as failure to maintain a safe workplace and negligent hiring and retention.105

Spikes in defamation lawsuits against the alleged wrongdoer, as well as retaliatory defamation lawsuits against the victim, have also been reported following #MeToo.106 These claims are particularly common when the statute of limitations for sexual assault or sexual harassment claims has passed.107 In addition to extending the ability of victims to bring a claim, defamation lawsuits also provide one of the few ways to address the additional reputational injuries that women often sustain when they accuse a high-profile harasser.108 For example, high profile defamation lawsuits have been brought against Bill Cosby, Donald Trump, Roy Moore, and Bill O’Reilly.109 In this sense they might also be thought of as a mechanism for fighting the underlying gender inequality that allows men to take advantage of being more readily believed than women.110

6. Government officials

Our comprehensive analysis of the public record reveals that #MeToo also spurred a series of public accusations of government officials, many of whom are responsible for passing laws on this very issue.111 Those accused include state legislators, members of the U.S. Congress, and other elected and appointed officials.112 All but three of the 138 people accused in our data set are men. Some have been accused by more than a dozen women.113 Most of the allegations pertain to behavior within the workplace, including unwanted kissing and groping, masturbating in front of others, sending sexually explicit photos, and discussing sexual fantasies.114 Some of the reported misconduct has also occurred outside of official government responsibilities, including domestic violence, sexual misconduct with minors, and sex trafficking.115

Many of these claims have been settled by officials, who pay victims large settlements using taxpayer dollars.116 Other claims have prompted internal investigations into the toxic workplace cultures that feed this type of behavior.117 Republicans and Democrats shared a relatively even distribution of the allegations, constituting about 48.5 percent and 43.5 percent of accusations, respectively.118 Reports are also spread fairly evenly across the country.119 Alleged misconduct was notably high compared to the overall population in Ohio, Kentucky, Alaska, and Washington, D.C.120

Most of the accused officials in our findings have since fallen from power.121 Of the 25 appointed officials, 23 have been fired or resigned.122 Of the 111 elected officials, 76 are no longer in office.123 Moreover, some of these officials also face legal action, including at least 7 civil lawsuits and 12 criminal charges. This type of accountability is historically unprecedented.124 Nonetheless, of the 27 government officials accused of sexual misconduct who ran for office in the 2018 midterm elections, 23 were re-elected or elected to a new government position.125 These statistics are consistent with typical election trends, considering that an average of 92 percent of state legislators are re-elected in any given election year.126 So, for those who did not step down and instead, sought reelection, sexual misconduct allegations appeared to have little influence on the outcome.

VII. Conclusion

As important as individual stories are for achieving empowerment and justice at the personal level, the magnitude of the social media response reveals something significant about the pervasiveness of, and tolerance for, harassment and abuse in our society. By encouraging women and men to speak out and supporters around the world to act, our analysis suggests that #MeToo is changing our society’s collective understanding of sexual harassment and assault, and reducing our collective tolerance for it. Not only are people talking about issues online, but by using a simple, shared phrase they have named and consolidated the conversation and made the injury more visible. There is also evidence that the conversations are sparking broader offline organizing efforts and prompting victims to claim their legal rights, seek protection of the law, and demand better laws when the protection is inadequate.127

In this new paradigm of collective action, at least in the context of #MeToo, tweeting has not eclipsed traditional social movement activity, but rather has been a catalyst and communications tool for action offline. While social media allows individuals to disseminate information, organize, and act without dependence on traditional movement institutions, organizations like Time’s Up Legal Defense continue to play a central role in pushing for remedies and reform. Legal reform also has not been abandoned within the new paradigm as indicated by the increase in legislative activity around harassment and gender equity following the #MeToo surge online.

Social media activism is powerful when it effectively names a pervasive injury and the inequality that sustains it, when it consolidates communication about the injury, and when it inspires action and reform. Like #BlackLivesMatter, #MeToo has done just this. But both movements seek to address the stickiest kinds of cultural norms, the ones that are so ingrained that we often do not recognize them; they are the implicit default ideas about race and gender. For this reason, change can be uneven, uncertain, and subject to backlash. What we do not yet know is whether the #MeToo movement will maintain its momentum and whether these changes in the short run will translate to broader and more sustainable cultural, legal, and political change in the long run.

- 1Although women are the focus of this essay, men, trans, and gender non-binary people are also participants. For example, actor Terry Crews is a male victim who has been vocal in the #MeToo movement.

- 2See Kara Fox & Jan Diehm, #MeToo’s Global Moment: The Anatomy of a Viral Campaign, CNN (Nov. 9, 2017), https://www.cnn.com/2017/11/09/world/metoo-hashtag-global-movement/index.html [https://perma.cc/M85F-XMTM].

- 3See Clay Shirky, The Political Power of Social Media: Technology, the Public Sphere, and Political Change, 90 Foreign Affairs 28, 28–29 (2011).

- 4This Essay does not focus on the computer science or data analytic methods used to extract this information. For a more detailed discussion of that see: Lisa Singh, Linda Li, Laila Wahedi, Yifang, Wei, Jamillah Williams, & Naomi Mezey. #metoo—An Analytic Framework for Characterizing an Evolving Social Media Movement (in prep).

- 5Stop Street Harassment, The Facts Behind the #MeToo Movement: A National Study on Sexual Harassment and Assault 7 (2018), http://www.stopstreetharassment.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Full-Report-2018-National-Study-on-Sexual-Harassment-and-Assault.pdf [https://perma.cc/5HNM-ERMK].

- 6Id.

- 7See generally, Stop Street Harassment, supra note 8; Banu Ozkazanc-Pan, On Agency and Empowerment in a #MeToo World, Gender, Work & Org., 1–9 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12311 [https://perma.cc/CWD8-ZHY7]; Paolo Gerbaudo, Tweets and the Streets: Social Media and Contemporary Activism (2012); Alexandra Segerberg & W. Lance Bennett, Social Media and the Organization of Collective Action: Using Twitter to Explore the Ecologies of Two Climate Change Protests, 14 Commc’n Rev. 197 (2011).

- 8Stop Street Harassment, supra note 8, at 8.

- 9Id.

- 10Lynn Langton et al., Bureau of Justice Stat., U.S. Dep’t of Justice, National Crime Victimization Survey, 2006–2010 1 (2012), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/vnrp0610.pdf [https://perma.cc/X3D3-RJVJ].

- 11The Criminal Justice System: Statistics, Rape, Abuse & Incest Nat’l Network (2017), https://www.rainn.org/statistics/criminal-justice-system [https://perma.cc/5B26-CGFN].

- 12Harassment-Free Workplace Series: A Focus on Sexual Harassment, Soc’y for Human Resource Mgmt (Jan. 31, 2018), https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/trends-and-forecasting/research-and-surveys/Pages/A-Focus-on-Sexual-Harassment.aspx [https://perma.cc/2XY6-97LR] (last visited Jan. 21, 2019).

- 13SeeAnne Lawton, Between Scylla and Charybdis: The Perils of Reporting Sexual Harassment, 9 U. Pa. J. Lab. & Emp. L. 603, 632 (2007).

- 14Id.

- 15See, e.g., Rebecca Solnit, The Kavanaugh Case Shows We Still Blame Women for the Sins of Men, Guardian (Sept. 21, 2018), https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/sep/21/brett-kavanaugh-blame-women-anita-hill-cosby-weinstein (last visited Feb. 25, 2019).

- 16Tarana Burke is currently Senior Director at Girls for Gender Equity, a nonprofit that helps schools, workplaces, and other groups improve policies concerning sexual violence at. In 2003 Burke founded “Just Be,” an all-girls program for young black women that provided assistance to survivors of sexual violence. See Ania Alberski, Former Phila. Activist Tarana Burke among the ‘Silence Breakers’ Honored by Time Magazine, The Daily Pennsylvanian (Dec. 10, 2017), https://www.thedp.com/article/2017/12/philly-woman-silence-breakers-metoo-penn-upenn-sexual-assault [https://perma.cc/K56A-4KSU]; Staff, Girls for Gender Equity, https://www.ggenyc.org/about/staff/ (last visited Feb. 3, 2019).

- 17See Abby Ohlheiser, The Woman Behind ‘MeToo’ Knew the Power of the Phrase When She Created It—10 Years Ago, Wash. Post (Oct. 19, 2017), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-intersect/wp/2017/10/19/the-woman-behind-me-too-knew-the-power-of-the-phrase-when-she-created-it-10-years-ago/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.4067dc89d58d [https://perma.cc/H5NH-EELJ] (last visited Jan. 21, 2019).

- 18Alyssa Milano is an American actress and activist. See Elizabeth Chuck, Before #MeToo, Before Doug Jones, Alyssa Milano’s Activism Started with a Kiss on TV, NBC News (Dec. 16, 2017), https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/metoo-doug-jones-alyssa-milano-s-activism-started-kiss-tv-n829466 [https://perma.cc/AKU7-YWLX].

- 19Alyssa Milano (@Alyssa_Milano), Twitter (Oct. 15, 2017, 1:21 PM), https://twitter.com/alyssa_milano/status/919659438700670976?lang=en [https://perma.cc/72N3-TJ6W].

- 20Jodi Kantor & Megan Twohey, Harvey Weinstein Paid off Sexual Harassment Accusers for Decades, N.Y. Times (Oct. 5, 2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/05/us/harvey-weinstein-harassment-allegations.html [https://perma.cc/5C89-5DTK].

- 21Fox & Diehm, supra note 2.

- 22The #MeToo Research Collaboration, Massive Data Inst. & Gender + Just. Initiative, http://metoo.georgetown.domains/ [https://perma.cc/J6T8-F69V]; Michael Cohen, The #MeToo Movement: Findings from the Peoria Project, Geo. Wash. U. (2018), https://gspm.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaxdzs2286/f/downloads/2018%20RD18%20MeToo%20Presentation.pdf [https://perma.cc/UNH5-5LGR]; Abby Ohlheiser, How #MeToo Really Was Different, According to Data, Wash. Post (Jan. 22, 2018), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-intersect/wp/2018/01/22/how-metoo-really-was-different-according-to-data/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.225aacf76ae2 [https://perma.cc/8X36-JY3K].

- 23Monica Anderson & Skye Toor, How Social Media Users Have Discussed Sexual Harassment Since #MeToo Went Viral, Pew Res. Ctr. (October 11, 2018), http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/10/11/how-social-media-users-have-discussed-sexual-harassment-since-metoo-went-viral/ [https://perma.cc/ZX7J-B5HB].

- 24MDI Research Collaborative finding using tweets collected through the Twitter API.

- 25After a Year of #MeToo, American Opinion Has Shifted against Victims, The Economist (Oct. 15, 2018), https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2018/10/15/after-a-year-of-metoo-american-opinion-has-shifted-against-victims [https://perma.cc/S63X-5YGW].

- 26Shirky, supra note 6; Gerbaudo, supra note 10; Dhiraj Murthy, Introduction to Social Media, Activism, and Organizations, Soc. Media + Soc’y, 1 (2018). See generally Clay Shirky, Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations (2008).

- 27Gerbaudo, supra note 10; see also Shirky, supra note 6.

- 28Gerbaudo, supra note 10; Mary Butler, Clicktivism, Slacktivism, or “Real” Activism? Cultural Codes of American Activism in the Internet Era, 20 (graduate thesis, University of Colorado) (on file with University of Colorado, Boulder) (2011) [https://perma.cc/Y3GX-ZBRP]; Sam Gustin, Social Media Sparked, Accelerated Egypt’s Revolutionary Fire, Wired (Feb. 11, 2011), https://www.com/2011/02/egypts-revolutionary-fire/ [https://perma.cc/9LYZ-HQRD].

- 29Gustin, supra note 31.

- 30Gerbaudo, supra note 10.

- 31Compare Jonathan Obar et al., Advocacy 2.0: An Analysis of How Advocacy Groups in the United States Perceive and Use Social Media as Tools for Facilitating Civic Engagement and Collective Action, 2 J. Info. Pol’y 1 (2012); Yochai Benkler, The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom (2007); and Manuel Castells, The Rise of the Network Society (The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture) (1996); with Bruce Bimber, Information and American Democracy: Technology in the Evolution of Political Power (2003). See also W. Lance Bennett, Communicating Global Activism, 6 Info., Comm’n & Soc’y 143 (2003); Paolo Gerbaudo & Emiliano Trere, In Search of the “We” of Social Media Activism: Introduction to the Special Issue on Social Media and Protest Identities, 18 Info., Comm’n & Soc’y 865 (2015); Shirky, supra note 6.

- 32Obar et al., supra note 34; Benkler, supra note 34.

- 33Jose Ortiz & Arvind Tripathi, Resource Mobilization in Social Media: The Role of Influential Actors, 25th Eur. Conf. on Info. Sys., 3049–59 (2017).

- 34Gerbaudo, supra note 10; Shirky, supra note 6; Bijan Stephen, Social Media Helps Black Lives Matter Fight the Power, Wired (Nov. 2015), https://www.wired.com/2015/10/how-black-lives-matter-uses-social-media-to-fight-the-power/ [https://perma.cc/RZ3M-58V5].

- 35Ohlheiser, supra note 19.

- 36Deen Freelon et al., Beyond the Hashtags: #Ferguson, #Blacklivesmatter, and the Online Struggle for Offline Justice, Ctr. for Media & Soc. Impact, 36–70 (2016), http://archive.cmsimpact.org/sites/default/files/beyond_the_hashtags_2016.pdf [https://perma.cc/5A8X-PH6K].

- 37Yasmin Aslam, #LoveWins on the Internet, MSNBC (June 27, 2015), http://www.msnbc.com/msnbc/love-wins-the-internet [https://perma.cc/G9ND-QYRX].

- 38Id.

- 39Monica Anderson et al., Pew Res. Ctr., Activism in the Social Media Age 5 (July 11, 2018).

- 40Id. at 13.

- 41Id.

- 42These surges have occurred, for example, when black men, women, and children have been killed by the police and when officers are not indicted or acquitted of charges.

- 43See, e.g., U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Reports on Police Killings: Ferguson, Cleveland, Baltimore, and Chicago (2017); Trymaine Lee, Black Lives Matter Releases Policy Agenda, NBC News (Aug. 1, 2016), https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/black-lives-matter-releases-policy-agenda-n620966 [https://perma.cc/9ZQY-RYA9]; German Lopez, This Moment at the DNC Shows Democrats Have Embraced Black Lives Matter, Vox (July 26, 2016), https://www.vox.com/2016/7/26/12291274/democratic-convention-police-violence-mothers-of-the-movement [https://perma.cc/XB95-S4RH].

- 44Shaked Spier, Collective Action 2.0: The Impact of Social Media on Collective Action 140 (2017); Stephen, supra note 37.

- 45See generally Yarimar Bonilla & Jonathan Rosa, #Ferguson: Digital Protect, Hashtag Ethnography, and the Racial Politics of Social Media in the United States, 42 J. Am. Ethnological Soc. 4, 8 (2015); Gerbaudo & Trere, supra note 34; Stephen, supra note 37. Although a digital divide remains along race and socioeconomic lines, the Internet and social media networks are now easy to access across a broad swath of socio-economic and geographic regions.

- 46Shirky, supra note 6.

- 47Spier, supra note 47.

- 48Shirky, supra note 6; Obar et al., supra note 34.

- 49N. L. Cabrera et al., Activism or Slacktivism? The Potential and Pitfalls of Social Media in Contemporary Student Activism, J. Diversity in Higher Educ., 4 (Apr. 2017). See also Malcolm Gladwell, Small Change: Why the Revolution Will Not Be Tweeted, New Yorker (Oct. 4, 2010), https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/10/04/small-change-malcolm-gladwell [https://perma.cc/Y6V7-PRYP].

- 50Noah Berlatsky, Hashtag Activism Isn’t a Cop-Out, Atlantic (Jan. 7, 2015), https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/01/not-just-hashtag-activism-why-social-media-matters-to-protestors/384215/ [https://perma.cc/X38Y-XKHS].

- 51Laura Seay, Does Slacktivism Work?, Wash. Post (March 12, 2014), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2014/03/12/does-slacktivism-work/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.6ed30ffa845f [https://perma.cc/89QD-Y2GW].

- 52Id.

- 53Id.

- 54Berlatsky, supra note 53; Henrik Serup Christensen, Political Activities on the Internet: Slacktivism or Political Participation by Other Means?, First Monday (Feb. 2011), https://uncommonculture.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/3336 [https://perma.cc/8HHR-Y47W]; Monica Anderson et al., supra note 42; Kirk Kristofferson et al., The Nature of Slacktivism: How the Social Observability of an Initial Act of Token Support Affects Subsequent Prosocial Action, 40 J. Consumer Res. 1149, 1149 (2014).

- 55Megha Mohan, Secret World: The Women in the UK Who Cannot Report Sexual Abuse, BBC News (March 27, 2018), https://www.bbc.com/news/in-pictures-43499374 [https://perma.cc/KWF8-JE6H].

- 56The #MeToo Research Collaboration supra note 25.

- 57The #MeToo Research Collaboration supra note 25; Anderson & Toor, supra note 26.

- 58The #MeToo Research Collaboration supra note 25; (we use the Twitter streaming Application Programming Interface (API) to collect tweets; this is an analysis of tweets collected between October 2017 and October 2018).

- 59We do not remove bots because they are engaging in conversation, but we do remove SPAM, i.e. ads and dead hyperlinks. SPAM makes up approximately 7% of the stream.

- 60Cara Buckley, Powerful Hollywood Women Unveil Anti-Harassment Action Plan, N.Y. Times (Jan. 1, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/01/movies/times-up-hollywood-women-sexual-harassment.html?hp&action=click&pgtype=Homepage&clickSource=story-heading&module=first-column-region®ion=top-news&WT.nav=top-news&_r=1 [https://perma.cc/T3EJ-L3YL].

- 61Gladwell, supra note 52.

- 62Ginia Bellafante, The #MeToo Movement Changed Everything. Can the Law Catch Up?, N.Y. Times (Nov. 21, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/21/nyregion/metoo-movement-schneiderman-prosecution.html [https://perma.cc/NP3G-2WPR]; 2018 Brings #MeToo Laws Nationwide, WNYC (Dec. 31, 2018), https://www.wnycstudios.org/story/2018-brings-metoo-laws-nationwide [https://perma.cc/M9Z2-QHYL].

- 63Daniella Silva, McDonald’s Workers Go on Strike over Sexual Harassment, NBC News (Sep. 18, 2018), https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/mcdonald-s-workers-go-strike-over-sexual-harassment-n910656 [https://perma.cc/9QZ8-KFKW].

- 64Rachel Abrams, McDonald’s Workers Across the U.S. Stage #MeToo Protests, N.Y. Times (Sep. 18, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/18/business/mcdonalds-strike-metoo.html [https://perma.cc/GK64-N7UM]; Sarah Whitten, McDonald’s Employees Stage First #MeToo Strike in Chicago, Alleging Sexual Harassment, USA Today (Sep. 18, 2018), https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/food/2018/09/18/mcdonalds-employees-metoo-strike-sexual-harassment/1349981002/ [https://perma.cc/29KK-PUYP].

- 65Seema Mody, Hotels are Arming Workers with Panic Buttons to Combat Harassment, CNBC (Sep. 6, 2018), https://www.cnbc.com/2018/09/06/major-hotels-arm-workers-with-panic-buttons-to-fight-harassment.html [https://perma.cc/FHX9-ZJG6].

- 66Id.

- 67Daisuke Wakabayashi et al., Google Walkout: Employees Stage Protest Over Handling of Sexual Harassment, N.Y. Times (Nov. 1, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/01/technology/google-walkout-sexual-harassment.html [https://perma.cc/UFM5-C27B].

- 68Jilian D’Onfro, Google CEO, in Internal Memo, Supports Employee Walkout in the Wake of Report on Sexual Misconduct, CNBC (Oct. 30, 2018), https://www.cnbc.com/2018/10/30/google-ceo-sundar-pichai-supports-employee-walk-out-in-memo.html [https://perma.cc/L2E8-4XLR].

- 69Daisuke Wakabayashi & Jessica Silver-Greenberg, Facebook to Drop Forced Arbitration in Harassment Cases, N.Y. Times (Nov. 9, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/09/technology/facebook-arbitration-harassment.html [https://perma.cc/B98Y-Z5M9].

- 70Buckley, supra note 63.

- 71Id.

- 72The #MeToo Research Collaboration, supra note 25 (Our analysis shows that <1% of those posting #MeToo are black.). See Charisse Jones, When Will MeToo Become WeToo? Some Say Voices of Black Women, Working Class Left Out, USA Today (Oct. 5, 2018), https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2018/10/05/metoo-movement-lacks-diversity-blacks-working-class-sexual-harassment/1443105002/ [https://perma.cc/2KT6-2BRA]. See generally Angela Onwuachi-Willig, What About #UsToo?: The Invisibility of Race in the #MeToo Movement, 128 Yale L. J. 105 (2018).

- 73See Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund—Stats & Numbers, Nat’l Women’s L. Ctr., https://nwlc.org/resources/times-up-legal-defense-fund-stats-numbers/ [https://perma.cc/BT8Z-FGJP] (last visited February 17, 2019).

- 74U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, EEOC Releases Preliminary FY 2018 Sexual Harassment Data (Oct. 4, 2018), https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/newsroom/release/10-4-18.cfm [https://perma.cc/WZ8S-6N8G].

- 75Julia Horowitz, Workplace Sexual Harassment Claims Have Spiked in the #MeToo Era, CNN (Oct. 5, 2018), https://www.cnn.com/2018/10/04/business/eeoc-sexual-harassment-reports/index.html [https://perma.cc/92RS-JFMG].

- 76Eric Bachman, In Response To #MeToo, EEOC Is Filing More Sexual Harassment Lawsuits and Winning, Forbes (Oct. 5, 2018), https://www.forbes.com/sites/ericbachman/2018/10/05/how-has-the-eeoc-responded-to-the-metoo-movement/#33a7edf87475 [https://perma.cc/U5RC-MDCE]; U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, What You Should Know: EEOC Leads the Way in Preventing Workplace Harassment, https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/newsroom/wysk/preventing-workplace-harassment.cfm [https://perma.cc/832W-CFVR] (last visited Feb. 3, 2019).

- 77U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2018 Performance Report 14 (Nov. 15, 2018), https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/plan/upload/2018par.pdf [https://perma.cc/TX3R-3PRU].

- 78Id. at 32.

- 7942 U.S.C. § 2000b. Small employers refer to employers with less than 15 employees. See Katherine V.W. Stone, Legal Protections for Atypical Employees: Employment Law for Workers without Workplaces and Employees without Employers, 27 Berkeley J. Emp. & Lab. L. 251, 251, 263 (2006).

- 8042 U.S.C. § 2000e-2 (2006); Joanna Grossman, Moving Forward Looking Back: A Retrospective on Sexual Harassment Law, 95 B.U. L. Rev. 1029, 1043 (2015) (explaining that the statute of limitation is “180 or 300 days, depending on the level of coordination between the federal and state anti-discrimination agencies”); National Women’s Law Center, Selected Title IX Practice Issues: Breaking Down Barriers 91 (2017), https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/BDB07_Ch6.pdf [https://perma.cc/N5AF-7JML].

- 81Vasundhara Prasad, If Anyone Is Listening, #MeToo: Breaking the Culture of Silence around Sexual Abuse through Regulating Non-disclosure Agreements and Secret Settlements, 59 B.C. L. Rev. 2507, 2507 (2018).

- 82Jean R. Sternlight, Mandatory Arbitration Stymies Progress Towards Justice in Employment Law: Where To, #MeToo?, 54 Harv. C.R.-C.L. L. Rev. 1, 2 (2019).

- 83Methodology: using Legiscan, we performed a legislative search for each state for the legislative sessions incorporating bills introduced from October 2016-present (2017 & 2018). Our initial search was: “sexual harassment” OR “equal pay” OR “sexual misconduct” OR “gender equity” OR “gender equality.” From there, we searched each individual bill to see if there were any parts of the bill that applied generally to harassment, equal pay, gender equity, whether it was through increased awareness, mandatory training, or some other expansion or limitation on current law.

- 84Governor Signs Jackson’s #MeToo Bills to Combat Sexual Harassment in the Workplace, (Oct. 01, 2008), https://sd19.senate.ca.gov/news/2018-10-01-governor-signs-jacksons-metoo-bills-combat-sexual-harassment-workplace [https://perma.cc/DLX2-NCRA]; Rebecca Beitsch, #MeToo Has Changed Our Culture. Now It’s Changing Our Laws, PEW Res. Ctr. (Jul. 31, 2008), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2018/07/31/metoo-has-changed-our-culture-now-its-changing-our-laws [https://perma.cc/DW3S-QUJD].

- 85Id.

- 86Id.

- 87Id.

- 88Id.

- 89S. Res. 330, 115th Cong. (2017) (enacted).

- 90132 Stat 5297 (2018).

- 91131 Stat. 1283 (2017).

- 92See supra note 86.

- 93Id.

- 94Id.

- 95Id.

- 96Id.

- 97See supra note 86.

- 98Id.

- 99Id.

- 100Id.

- 101Id.

- 102Martha Chamallas, Will Tort Law Have Its #MeToo Moment?, 11 J. Tort L. 39, 46–47 (2018); Rebecca Hanner White, Title VII and the #MeToo Movement, 68 Emory L. J. Online 1014, 1016 (2018). See generally Martha Chamallas, Discrimination and Outrage: The Migration from Civil Rights to Tort Law, 48 WM. & MARY L. REV. 2115 (2007).

- 103See White, supra note 105, at 1022.

- 104Rebecca Hanner White, Title VII and the #MeToo Movement, 68 Emory L. J. Online 1014, 1024 (2018).

- 105Ellen M. Bublick, Tort Suits Filed by Rape and Sexual Assault Victims in Civil Courts: Lessons for Courts, Classrooms and Constituencies, 59 SMU L. Rev. 55 (2006); White, supra note 105, at 1016.

- 106Mark Mulholland & Elizabeth Sy, Victim Defamation Claims in the Era of #MeToo, N.Y. L. J. (Aug. 1, 2018).

- 107White, supra note 105, at 1022.

- 108See Anna North, The Summer Zervos Sexual Assault Allegations and Lawsuit against Donald Trump, Explained, Vox (March 26, 2018), https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2018/3/26/17151766/summer-zervos-case-trump-lawsuit-sexual-assault-allegations (last visited February 27, 2019) [https://perma.cc/XB74-2Z3F].

- 109Daniel Jackson, Sex-Assault Accusers Turn to Defamation Lawsuits in #MeToo Era, Court-house News Serv. (Jan. 25, 2018), https://www.courthousenews.com/sex-assault-accusers-turn-to-defamation-lawsuits-in-metoo-era/ [https://perma.cc/ZVX3-JTBG].

- 110Defamation lawsuits are also a new obstacle for people with fewer resources filing sexual misconduct complaints under Title IX. Tyler Kingkade, As More College Students Say “MeToo,” Accused Men are Suing for Defamation, BuzzFeed News (Dec. 5, 2017), https:// www.buzzfeednews.com/article/tylerkingkade/as-more-college-students-say-me-too-accused-men-are-suing [https://perma.cc/2JHR-N2LZ]. Even the threat of a lawsuit can chill an alleged victim’s plans to speak out. Jackson, supra note 112.

- 111Jamillah Bowman-Williams, #MeToo and Public Officials: A post-election snapshot of allegations and consequences, Geo. U. L. Ctr. (Nov. 9, 2018), https://www.law.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/MeToo-and-Public-Officials.pdf [https://perma.cc/XDQ2-DN6Q]. Methodology: using LexisNexis, GoogleNews and NewspaperArchive, we performed a series of searches based on a series of key word phrases and indexed subject terms. These included, but were not limited to, words denoting general types of allegations, such as “sexual harassment,” “sexual misconduct,” “sexual assault,” “inappropriate touching,” and “abuse,” which were searched in association with positions such as “government official,” “state senator,” “legislative bodies,” “local government,” “Congress,” “assemblymen,” “governor,” “congressman,” and “state representative.” The search was limited to online and print newspapers and publications from the United States, and looked at reporting conducted from November 2016 to October 2018. Individual behavior is identified, and others accused of enabling or hiding another individual’s harassment or misconduct are also accounted for. In some circumstances the incident takes place in earlier years, but the accusation happened or was reported within the November 2016 to October 2018 timeframe.

- 112Id.

- 113Id.

- 114Id.

- 115Id.

- 116Peter Henning, Taxpayers Are Subsidizing Hush Money for Sexual Harassment and Assault, The Conversation (Nov. 5, 2017), https://theconversation.com/taxpayers-are-subsidizing-hush-money-for-sexual-harassment-and-assault-86451 [https://perma.cc/QF57-AZ59].

- 117See Bowman-Williams, supra note 114.

- 118Id.

- 119Id.

- 120Id.

- 121Id.

- 122See id.

- 123Id.

- 124Nathanial Rakich, We’ve Never Seen Congressional Resignations Like This Before, FiveThirtyEight (Jan. 29, 2018), https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/more-people-are-resigning-from-congress-than-at-any-time-in-recent-history/ [https://perma.cc/LLT3-KVYT].

- 125See Bowman-Williams, supra note 114.

- 126Ciara O’Neill, Money and Incumbency in State Legislative Races, 2015 and 2016, Follow The Money (Nov. 1, 2017), https://www.followthemoney.org/research/institute-reports/money-incumbency-in-2015-and-2016-state-legislative-races [https://perma.cc/6H2U-WEBH].

- 127Beitsch, supra, note 87.